Exploring .NET Core with ReSharper Ultimate

We recently started the EAP for ReSharper 9.1, and it might have been easy to miss that the EAP is not just for ReSharper, but for ReSharper Ultimate – that is, our entire .NET tools product range. Starting with ReSharper 9.0, we unified the way we both build and distribute our .NET tools, so that they share a common install. This has many benefits, from licensing to sharing in-memory caches between products. So not only is it the ReSharper 9.1 EAP, but it’s the EAP for dotCover 3.1, dotTrace 6.1, dotMemory 4.3 and dotPeek 1.4.

With EAP03, we’re introducing support for .NET Core to ReSharper Ultimate. This means you can get code coverage and performance and memory profiling for your .NET Core apps.

But let’s back up. What’s .NET Core?

This is Microsoft’s new, Open Source, cross platform .NET stack. It is the next generation of .NET, designed to replace the need for Portable Class Libraries by providing a common, modular .NET implementation across all platforms, including ASP.NET vNext. (One slightly confusing part is that it doesn’t replace the .NET Framework. This will still be Microsoft’s .NET stack on the Windows desktop, and will remain in use, and supported for both compatibility reasons and to support desktop apps, such as WPF.)

It’s made up of a couple of pieces – the CoreCLR project is the runtime, containing the JIT and the Garbage Collector, and the Base Class Library is being reimplemented in the CoreFX project.

One of the nice things about a .NET Core application is that it is xcopy deployable. That is, .NET Core apps don’t require an install, or a GAC, or anything. All of the files required to run an application can live in a single folder.

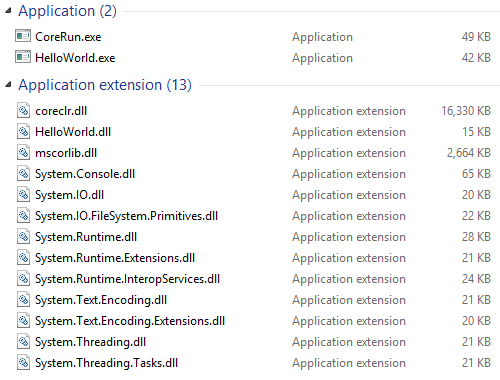

This test application is the HelloWorld app from the CoreFX Lab repo. As we can see, the folder contains everything we need to run the application. The BCL System assemblies are present, perhaps a few more than you’re used to on the desktop – this allows for a more modular distribution of the BCL, only distributing the assemblies you use. You can also see mscorlib.dll, which provides the primitive types, such as Object and String, and coreclr.dll, which is the actual runtime, including the JIT and the garbage collector. Most interestingly, we have three other files – HelloWorld.dll, CoreRun.exe and HelloWorld.exe.

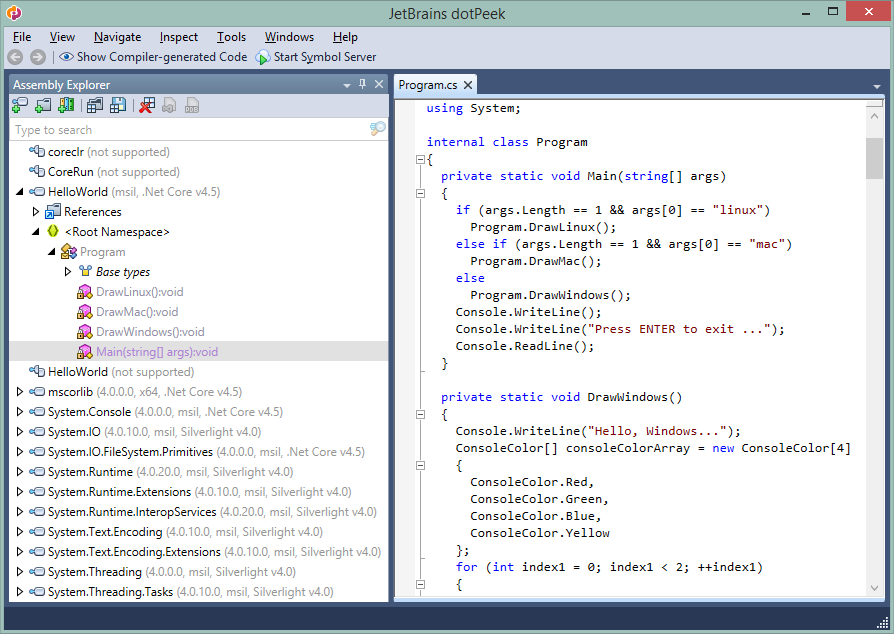

If we take a look at these files in dotPeek, we can see that the System assemblies and HelloWorld.dll are just normal looking assemblies, although they’re now targeting .NET Core v4.5, rather than the .NET Framework. Furthermore, we can see that HelloWorld.dll contains our Program class, with a normal static Main method – this is the entry point to the application. And coreclr is listed as “not supported”, as we know that’s a dll containing the native code for the runtime itself.

So what are HelloWorld.exe and CoreRun.exe?

These files are also coming up as “not supported” in dotPeek, and if we look at the their file sizes, we see that they’re both very small, only about 40Kb each. These files are native stubs, and are used to bootstrap the .NET Core runtime and launch the .NET application. The stub will load coreclr.dll, initialize the runtime and point it to the managed code to run.

The CoreRun.exe process is a generic launcher that requires the HelloWorld.dll to be passed in as a command line parameter, and provides extra command line parsing to enable attaching a debugger, and providing verbose output. The HelloWorld.exe process is simpler, and requires no command line parameters, automatically launching HelloWorld.dll and passing any command line parameters to the .NET application.

These stubs are required for .NET Core primarily to allow for running cross platform. Traditional .NET Framework applications combine the bootstrap stub and the .NET application code and metadata (HelloWorld.dll) so the .NET application just works transparently (in fact, versions of Windows later than Windows XP recognize .NET applications at the Operating System level, and bootstrap the .NET Framework automatically). But if we want to run the HelloWorld .NET application on OS X or Linux, then we can’t just run HelloWorld.exe – other operating systems don’t know how to launch .exe files, and might not even be Intel-based! So on other operating systems, the stub can be replaced with another executable, without having to replace the .NET application.

We can dive deeper into .NET Core applications, by profiling and analyzing them at runtime.

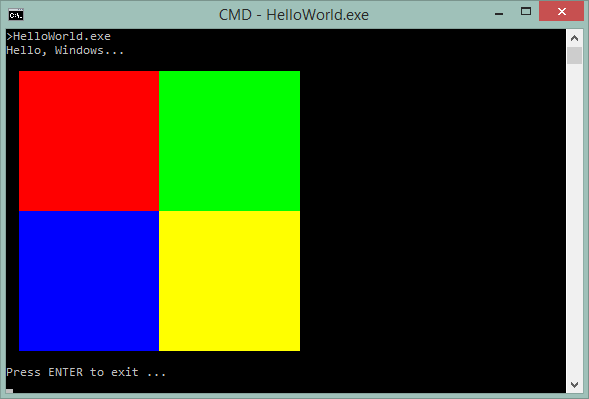

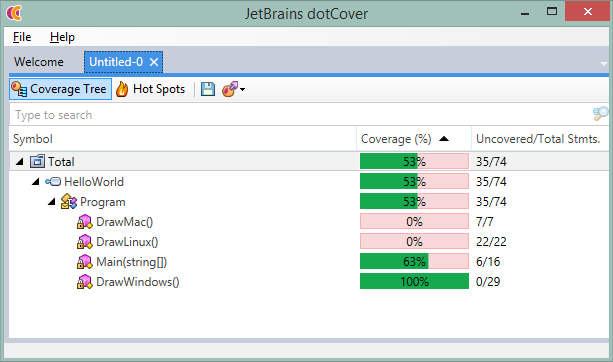

We can use dotCover to provide code coverage – note that DrawWindows is being called, but not DrawLinux or DrawMac. (While .NET Core is cross-platform, ReSharper Ultimate is a set of .NET Framework applications, using WPF, and as such, tied to Windows.)

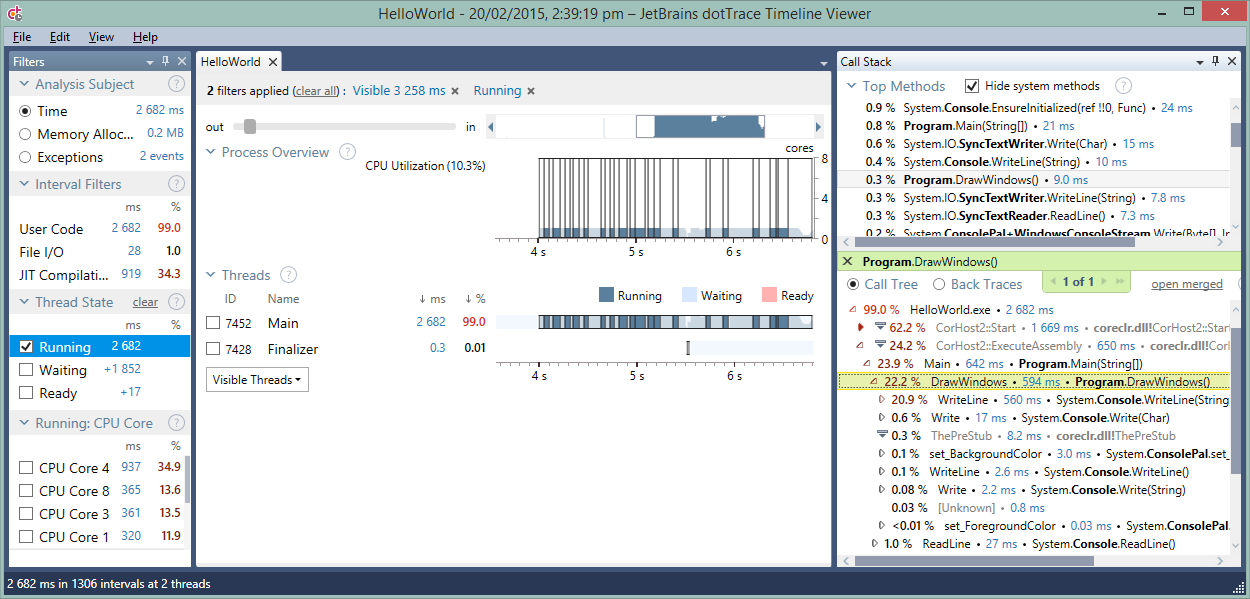

Performance profiling is handled by dotTrace, which can provide a nice timeline view of the performance of a .NET Core application, with powerful filtering capabilities to filter based on CPU, CPU state, thread and so on. Hopefully you’ll be working on slightly more interesting applications!

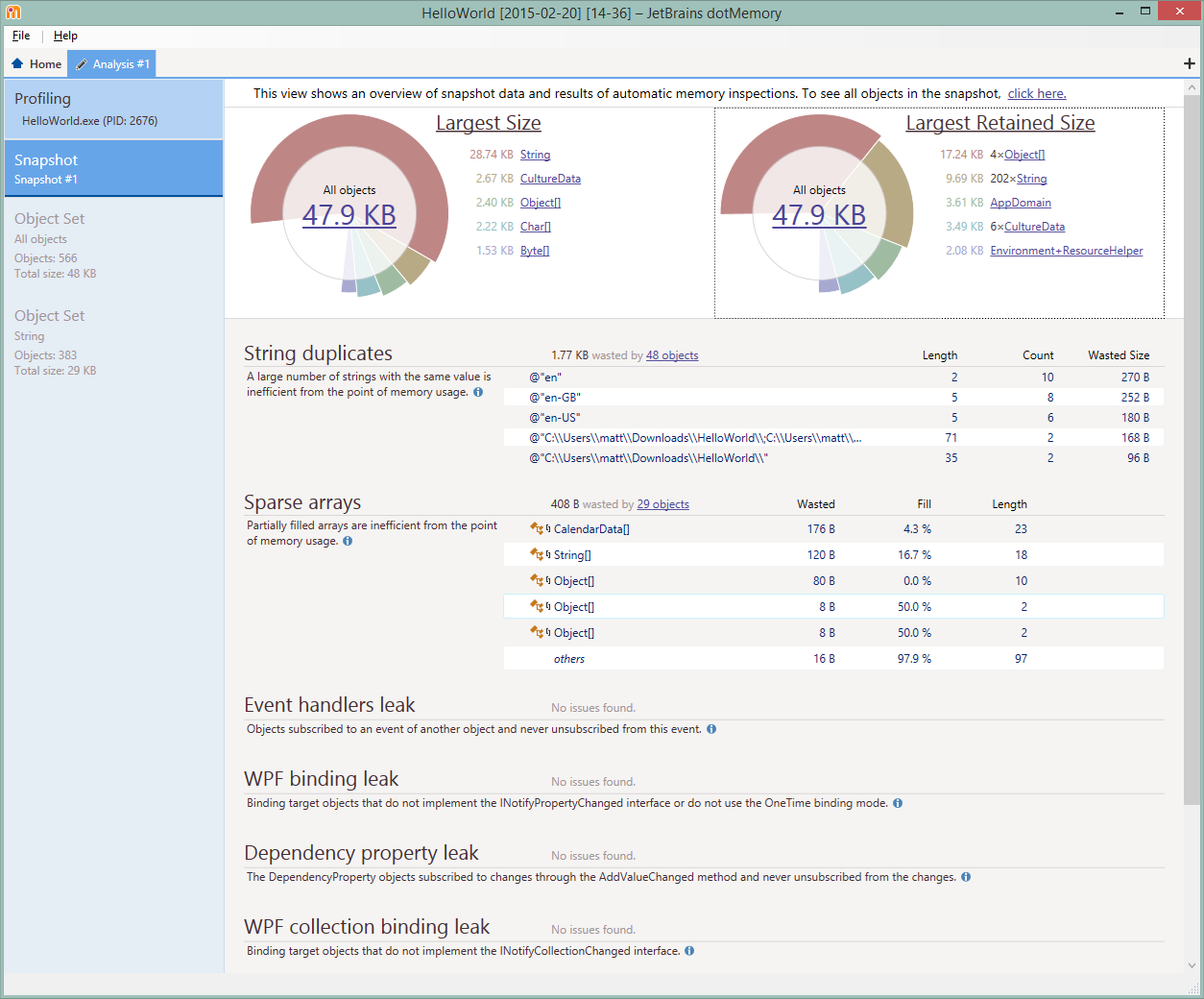

And finally, dotMemory will allow you to examine the memory allocations of .NET Core apps, too.

All of this support for .NET Core is handled transparently by ReSharper Ultimate. You simply need to start profiling or coverage for a .NET application, passing in either of the stubs as the startup application, and ReSharper Ultimate will do the rest.

Also, this is initial support. There are a few things that aren’t working correctly just now, but we’re working on them, and they should be fixed in future EAP builds.

Grab yourself a copy of the latest EAP and give it a go. There’s more to come. Stay tuned!

Subscribe to a monthly digest curated from the .NET Tools blog: