JetBrains AI

Supercharge your tools with AI-powered features inside many JetBrains products

Building AI Agents in Kotlin – Part 4: Delegation and Sub-Agents

Previously in this series:

- Building AI Agents in Kotlin – Part 1: A Minimal Coding Agent

- Building AI Agents in Kotlin – Part 2: A Deeper Dive Into Tools

- Building AI Agents in Kotlin – Part 3: Under Observation

In the previous installment, we saw how to set up tracing, which brings us to two new questions: What should we experiment with based on the information this tool provides? And what parts of our agent could we improve using its observations?

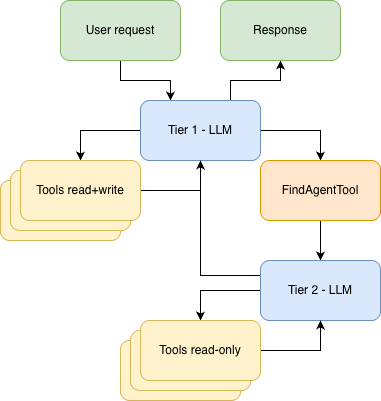

The first idea we had was to experiment with sub-agents, or more specifically, a find sub-agent. This will give us a chance to have a look at how Koog makes it easier to implement common patterns like sub-agents. Our hypothesis is that a find sub-agent might reduce overall cost while maintaining, or even improving, performance.

Why would we think that? Well, the main driver of cost is context growth. Each LLM request contains the full context from start to finish, which means each subsequent request is more expensive (at least in terms of input tokens) than the previous one. If we could limit context growth, especially early in the agent’s run, we might significantly reduce cost. An unnecessarily large context could also distract the agent from its core task. Therefore, by narrowing the context, we might even see a performance improvement, though that’s harder to predict.

The find functionality is particularly suited for removal from the long-term context. When searching for something, you typically open many files that don’t contain your target. Remembering those dead ends isn’t useful. Remembering what you actually found is. You could think of this as a natural way of compressing the agent’s history (we’ll look at actual compression in a later article).

This task is also a good candidate for a sub-agent because it’s relatively simple. That simplicity means we could also make use of the sub-agent’s ability to use a different LLM model. In this case, a faster and cheaper one. This offers flexibility that regular compression doesn’t.

Of course, we could have built a traditional procedural tool to do this. In fact, we did build one called RegexSearchTool, but for the purposes of this experiment, we put it inside the find agent rather than directly in the main agent. This approach provides us with flexibility in terms of model choice while also incorporating an extra layer of intelligence.

The find agent

To be able to have a sub-agent pattern, we first need a second agent. We’ve already covered agent creation in depth in Part 1 of the series, so we won’t spend much time on this now. However, a few details are still worth noting.

First, a minor point: We’re using GPT4.1 Mini for this sub-agent because its task is much simpler and doesn’t require a model as capable as the one used by the main agent.

Second, it’s useful to look at which tools this agent can access. Like the main agent, it has access to the ListDirectoryTool and ReadFileTool, but not the EditFileTool or ExecuteShellCommandTool. We’ve also given it access to the new procedural search tool we mentioned above, RegexSearchTool, which allows us to search a comprehensive range of files inside a folder and its subfolders using a regex pattern.

ToolRegistry {

tool(ListDirectoryTool(JVMFileSystemProvider.ReadOnly))

tool(ReadFileTool(JVMFileSystemProvider.ReadOnly))

tool(RegexSearchTool(JVMFileSystemProvider.ReadOnly))

}

For more detailed information, check out the full implementation here.

Building a find sub-agent

First things first – what is a sub-agent? A sub-agent is really quite simple; it is an agent that is being controlled by another agent. In this specific case, we are working with the agent-as-a-tool sub-agent pattern, where the sub-agent is running inside a tool that is provided to the main agent.

Creating a sub-agent turns out to be straightforward. We know a tool is essentially a function paired with descriptors that the agent can read to understand when and how to call it. We could simply define a tool whose .execute() function calls our sub-agent. But Koog provides tools to remove even this boilerplate:

fun createFindAgentTool(): Tool<*, *> {

return AIAgentService

.fromAgent(findAgent as GraphAIAgent<String, String>)

.createAgentTool<String, String>(

agentName = "__find_in_codebase_agent__",

agentDescription = """

<when to call your agent>

""".trimIndent(),

inputDescription = """

<how to call your agent>

""".trimIndent()

)

}

You could think of this as roughly equivalent to:

public class FindAgentTool(): Tool<FindAgentTool.Args, FindAgentTool.Result>() {

override val name: String = "__find_in_codebase_agent__"

override val description: String = """

<when to call your agent>

"""

@Serializable

public data class Args(

@property: LLMDescription(

"""

<how to call your agent>

"""

)

val input: String

)

@Serializable

public data class Result(

val output: String

)

override suspend fun execute(args: Args): Result = when {

output = findAgent.run(args.input)

Result(output)

}

}

In either case, the only things we need to do are:

- Create our sub-agent.

- Give it an

agentName. - Specify when to call the agent through the

agentDescriptionprompt. - Specify how to call the agent through the

inputDescriptionprompt.

The prompts are, perhaps, the trickiest part. There’s plenty of room for fine-tuning. But there’s some indication that newer LLMs need less precisely tuned prompts, so perfectly fine-tuned prompts may not be worth our time. We’re still exploring this topic ourselves, and it will take more experimentation to really come to a strong conclusion.

One thing we did notice is that, if we’re not careful with the prompts, the main agent sometimes confuses the find agent with a simple Ctrl+F / ⌘F function, sending only the tokens it wants to search for. That’s clearly suboptimal. With so little context, the find agent can’t reason about what it should actually be looking for. To address this, we include instructions requiring the main agent to specify why it’s looking for something. That way, the find agent can fully leverage its intelligence to find the actual thing the main agent is looking for.

""" This tool is powered by an intelligent micro agent that analyzes and understands code context to find specific elements in your codebase. Unlike simple text search (Ctrl+F / ⌘F), it intelligently interprets your query to locate classes, functions, variables, or files that best match your intent. It requires a detailed query describing what to search for, why you need this information, and an absolute path defining the search scope. ... """

| Query WITH highlighting (not Ctrl+F /⌘F) | Query WITHOUT highlighting (not Ctrl+F /⌘F) |

|---|---|

Search for changes in get_search_results regarding unnecessary joins to see if there are comment or logic on unnecessary joins. | get_search_results |

Search for environment variable usage with SKLEARN_ALLOW or similar in repository to find potential bypass of check_build. | SKLEARN_ALLOW |

We also noticed that the main agent sometimes still chooses to call the shell tool with a grep command instead of the find agent, which undermines the entire purpose of having a dedicated sub-agent. To avoid this pattern, we added this section to the main system prompt in order to push it harder:

""" ... You also have an intelligent find micro agent at your disposal, which can help you find code components and other constructs more cheaply than you can yourself. Lean on it for any and all search operations. Do not use shell execution for find tasks. ... """

This is the “natural compression” we mentioned in the opening. The find agent opens many files, follows dead ends, and explores the codebase. But the main agent only sees the results: relevant file paths, snippets, and explanations. All that exploration stays in the find agent’s context and disappears after it returns. Only the stuff that really mattered is then added to the main agent’s context.

The trade-offs

Using a sub-agent has its benefits, but it also has downsides. This is certainly the kind of change that warrants experimentation to show whether it delivers the benefits we’re hoping for without too many sacrifices.

The first trade-off is cost and time. While shortening the context in the main thread helps bring down the cost and time there, we now also have to pay and wait for a number of LLM calls in the sub-agent. The hope is that the total cost and time spent are less, but that depends on how the main agent uses the sub-agent. If it ends up doing a large number of small queries, that benefit might not materialize. We will look at the costs when we run the benchmarks again in a later section, and we will just assume that cost and time are correlated.

We did notice this happening in some of our runs, so we added a segment to the tool’s agentDescription that explains the issue to the main agent and tries to limit the frequency of such high volumes of small queries:

""" ... While this agent is much more cost efficient at executing searches than using shell commands, it does lose context in between searches. So give preference to clustering similar searches in one call rather than doing multiple calls to this tool. ... """

A second trade-off is that this approach treats context retention in a far more black-and-white way than humans do. We may not pull everything that happened in the past into active memory, but we do keep vague impressions of what happened and can retrieve additional context when needed. There are ways to model this kind of behavior, but they are far beyond the scope of the current iteration of our agent and are more related to the deep and complex subject of agentic memory.

Another challenge is that it creates more complexity in tracing. In Langfuse, we no longer only have to look at the trace of just one agent. Indeed, we might even need to look at the behavior from multiple perspectives – both the full view and each agent separately.

Think wider: The engineering team analogy

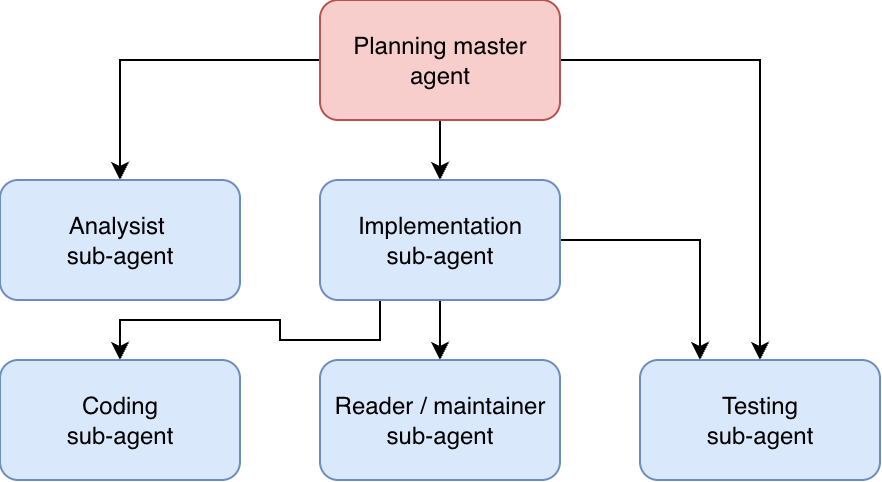

This technique of using sub-agents isn’t limited to simple cases like the find agent. You could, for example, replicate the separation of concerns in team structures by assigning analysis, implementation, testing, and planning to different sub-agents.

It’s still an open question whether an agent with all these capabilities does better or worse than a system where such capabilities are divided among sub-agents, but it’s not hard to imagine potential benefits. Think of Conway’s law: “Organizations design systems that mirror their communication structure.” One interpretation is that these communication structures evolved to discover efficient patterns worth keeping. The reverse Conway maneuver even suggests this is desirable.

Could the same be true for role distribution? Maybe the division of tasks across different specializations in software teams also evolved to discover efficient ways of working. Maybe LLMs could benefit from that, too.

Yet this is not guaranteed. The efficiencies might stem largely from spreading the human learning processes, and this might not apply to LLMs. But in the book Clean Code, we read about wearing different hats: a writer hat (creator), a reader hat (maintainer), and a tester hat (tester). The idea is to focus on one role without being distracted by the perspectives of the others. This suggests task division goes deeper than just learning efficiency, meaning it might indeed be relevant to LLMs.

All of this is to say that you can take sub-agents a lot further, but whether this is a beneficial approach is still unproven. It’s still an art form for now, not a hard science.

Benchmark results: Testing the hypothesis

We’re happy to report that our version without the find sub-agent shows a cost of about $814, or $1.63 per instance, while our version with this sub-agent shows a cost of about $733, or $1.47 per instance. That’s a 10% cost saving, which is definitely worth noting.

One interesting observation is how strongly the results depend on the choice of LLM for the sub-agent. In a smaller experiment, we tried keeping our sub-agent connected to GPT-5 Codex, and that dramatically increased the cost to $3.30 per example, averaged over 50 examples.

| Experiment | Success rate | Cost per instance |

| Part 03 (Langfuse) | 56% (278/500) | $1.63 ($814/500) |

| Part 04 (sub-agent GPT4.1 mini) | 58% (290/500) | $1.47 ($733/500) |

| Part 04 (sub-agent GPT-5 Codex) | 58% (29/50) | $3.30 ($165/50) |

However, it is interesting to note that we hypothesized two ways to reduce cost. The first was shrinking the context size through the natural compression achieved by task handoffs, and the second was offloading work to a cheaper model. The data suggests that just splitting off a sub-agent (and keeping the GPT-5 Codex model) actually increases the cost significantly, so our first method doesn’t seem to work, while our second (cheaper models) is the one that seems to do the trick – though this may not be rigorous proof.

As for performance improvements, we see a small uptick from 56% to 58%. This could be within the tolerance of statistical variance, but it’s encouraging that performance at least stayed consistent while we reduced costs.

Conclusion

We’ve seen that creating sub-agents is both simple and potentially powerful. Koog provides convenient tooling to streamline the process even further, leaving only the prompts for the agent-as-a-tool for you to define.

This technique clearly delivers worthwhile cost savings. We achieved nearly a 10% reduction – a clear, measurable improvement. The performance impact is less clear, but it does look like it might be some gains there, too.

At the same time, these kinds of evaluations are expensive. Even with reduced costs, this benchmark still totaled $730. That’s why, in the next part, we will take a closer look at another strategy for lowering costs: a more general approach to compression. In it, we’ll answer the question, “How do you prevent your context from growing indefinitely, and your costs growing with it?”

Subscribe to JetBrains AI Blog updates