Kotlin

A concise multiplatform language developed by JetBrains

The Journey to Compose Hot Reload 1.0.0

Compose Hot Reload has just been promoted to stable with our 1.0.0 release. We worked hard to build a technology that is easy to use and well-integrated into existing tools while also requiring zero configuration from users. The tool is bundled with Compose Multiplatform, starting from version 1.10 (see our dedicated release blog post). While we’re happy to have built tooling that doesn’t really require users to think about its technical implementation, we’re also immensely proud of the engineering behind the project. This blog post highlights some of the technical aspects we find most interesting and provides a high-level overview of how Compose Hot Reload works under the hood.

What we’ve built so far

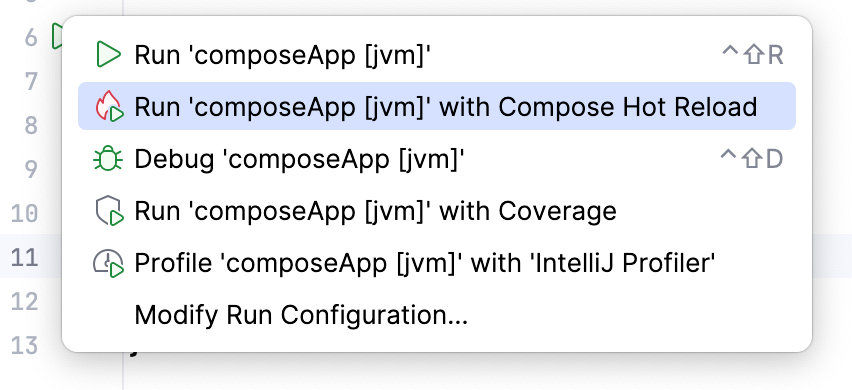

Compose Multiplatform is a declarative framework for sharing UIs across multiple platforms. Typically, if you’d like to launch a Compose application during development, you need to invoke the corresponding Gradle build tasks or otherwise launch it directly from within the IDE. This is also the case with Compose Hot Reload. Launching your application can be done by invoking the ./gradlew :myApp:hotRunJvm task or clicking Run with Compose Hot Reload in IntelliJ IDEA (assuming that the Kotlin Multiplatform plugin has already been installed).

Once the app launches in hot-reload mode, we see a floating toolbar right next to the application window. Changing code within IntelliJ IDEA and clicking Save (Cmd+S/Ctrl+S) will recompile the relevant code, perform a hot reload, and update the UI accordingly while preserving all parts of the state that are still considered valid.

Note: Screen recordings were made using the latest Compose Hot Reload version, 1.1, which differs visually from the 1.0 release but is conceptually equivalent.

Beyond simply changing the image resources, Compose Hot Reload lets you make almost arbitrary changes to your code, including but not limited to adding and removing functions, classes, and parameters – in short, all the kinds of changes you typically make during regular development.

The floating toolbar next to your application offers additional features, such as the ability to view logs, manually trigger a reload, and reset the UI state, as well as status indications and more. One of the most critical aspects of any hot-reload user experience, however, is communicating whether something went wrong. As the developer, you should always be acutely aware when reloading fails, causing your current code changes not to be reflected in the application. This could happen, for example, if you try to reload but the code cannot compile and requires your attention. In such cases, Compose Hot Reload will prominently display the error right in the target application’s window.

Let’s decompose Compose Hot Reload

Looking at the example above, let’s break Compose Hot Reload into its separate components and try to understand their individual purposes. In this section, we will recreate the process of building the core of Compose Hot Reload from the ground up, before proceeding to an explanation of the more technical details in the following sections.

First things first, the main requirement for Compose Hot Reload is the ability to update the application while it is running dynamically. To achieve this, we need to answer two questions: How do we reload code that is already running dynamically, and when should we do it? Without first answering these questions, the technology will not work.

The how part can be achieved in multiple ways in the JVM world: using custom classloaders, JVM hot swapping, and via various other methods. But what really makes Compose Hot Reload work so well is the JetBrains Runtime and its DCEVM implementation, which we’ll cover in detail later.

With the how being taken care of by DCEVM, we need to decide on the when. In other words, we need a way to run the application with DCEVM, detect when the user makes changes, recompile the code, and trigger the reload. That’s right, we need an integration with the application’s build system – a plugin that will provide us access to applications’ build and launch configurations.

It would seem that these components should provide everything we need, right? We can integrate with the application’s build system and trigger code reloads when the user changes their code! Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. You see, dynamically changing the code will not re-render the application’s UI. Even worse, changes to the code can now lead to errors when interacting with the UI. For example, what will happen if a user interacts with a button that no longer exists in the code? Therefore, we also need a way to interact with the Compose framework and re-render the UI when necessary. Luckily, the Compose Runtime provides APIs to invalidate states and re-render UIs, so we just need to correctly invoke them after the code is reloaded.

Good news: these three components are sufficient to provide the core functionality of Compose Hot Reload! But to truly elevate the user experience, we need to provide quick visual feedback on the current state of the hot reload. That’s why Compose Hot Reload also offers:

- In-app notifications about the state of any hot reloads.

- A custom toolbar next to the application window, which allows us to track the status and control the state of a given hot reload.

- Integration with an IDE that allows you to easily run the application with Compose Hot Reload and monitor its state.

Now that you have the rough outline of Compose Hot Reload, let’s dive deeper into its technical implementation. There is a lot to discover!

Reloading code dynamically: DCEVM and the JetBrains Runtime

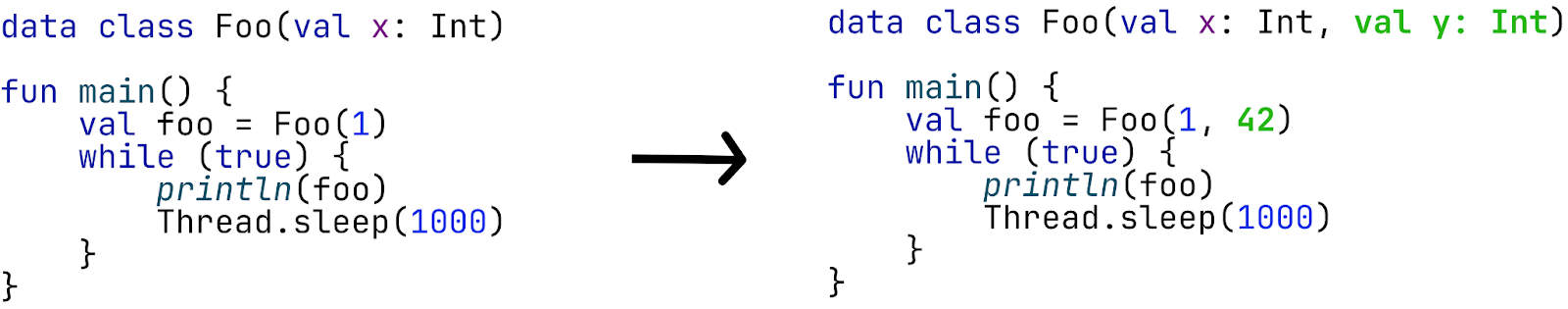

As previously mentioned, Compose Hot Reload relies heavily on the JetBrains Runtime to run the user code. Not only is the JetBrains Runtime specialized in building UI applications, it is also, to date, the only JVM to implement the DCEVM proposal published in 2011 by Thomas Würthinger, Christian Wimmer, and Lukas Stadler. This proposal enhances virtual machines’ ability to reload code. Where a regular JVM is limited to just reloading function bodies, DCEVM proposes “unrestricted and safe dynamic code evolution for Java”, which lifts the restrictions and supports almost arbitrary code changes. Here’s an example demonstrating how the JetBrains Runtime can perform more complex reloads:

The given program creates an instance of the class Foo and prints it every second in an endless loop.

When reloading, the class was modified, and a second property y was added. This begs the question: How can the program and the current state be reloaded in this way? Once the developer edits the code and compiles it, Compose Hot Reload sends the updated .class files to the currently running application, requesting that it reload. The request will be handled over several subsequent steps.

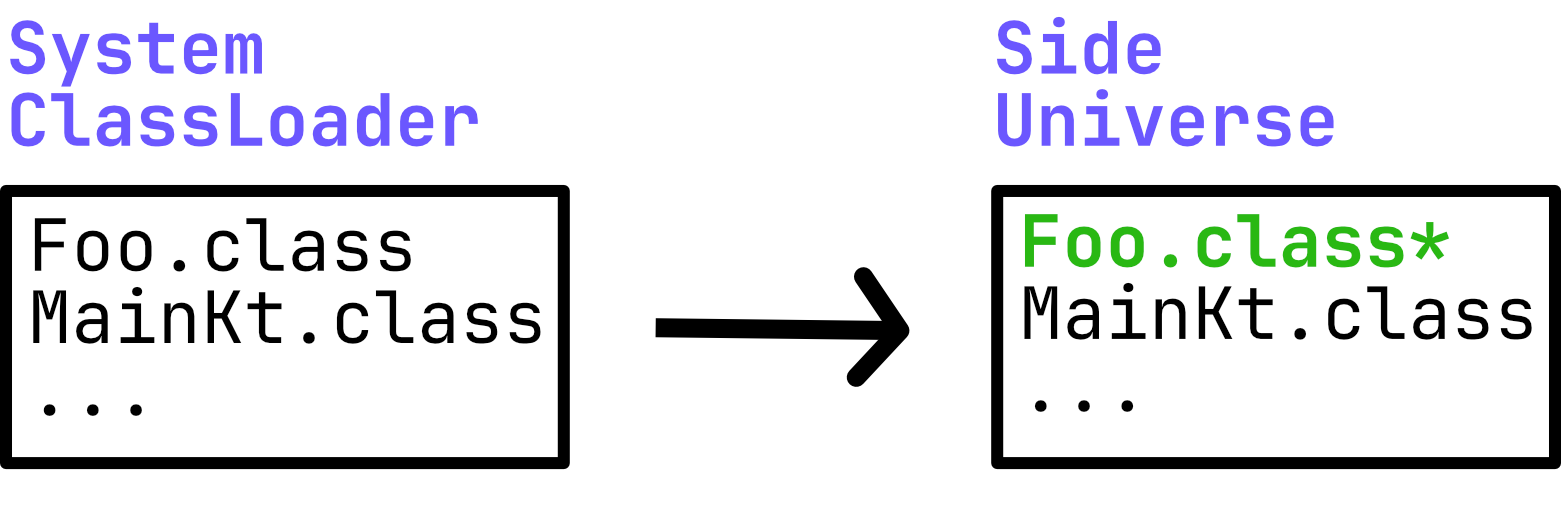

The first step can be called “verification”: The JetBrains Runtime will check whether the new .class files are valid and can generally be reloaded. If the code passes all checks, it can proceed to the second stage, “loading”. Then, the JetBrains Runtime will load all classes into what we call a “side universe”. This will represent the application code (all loaded classes) after the reload.

At this point, the side universe can be thought of as a second instance of your application, containing all updated application code, but without any state or threads executing. The above example shows the changed Foo.class marked in green, indicating that it points to an updated version of the class.

The current state of the application is then required to migrate objects to this side universe: We call this a “state transfer”. This state transfer is implemented as a special garbage collection (GC) pass. GC has a few properties that are useful for implementing the state transfer. Not only is it possible to “stop the world” (wait for all application threads to reach safe points), but GC is also allowed to allocate new memory and move objects to new locations!

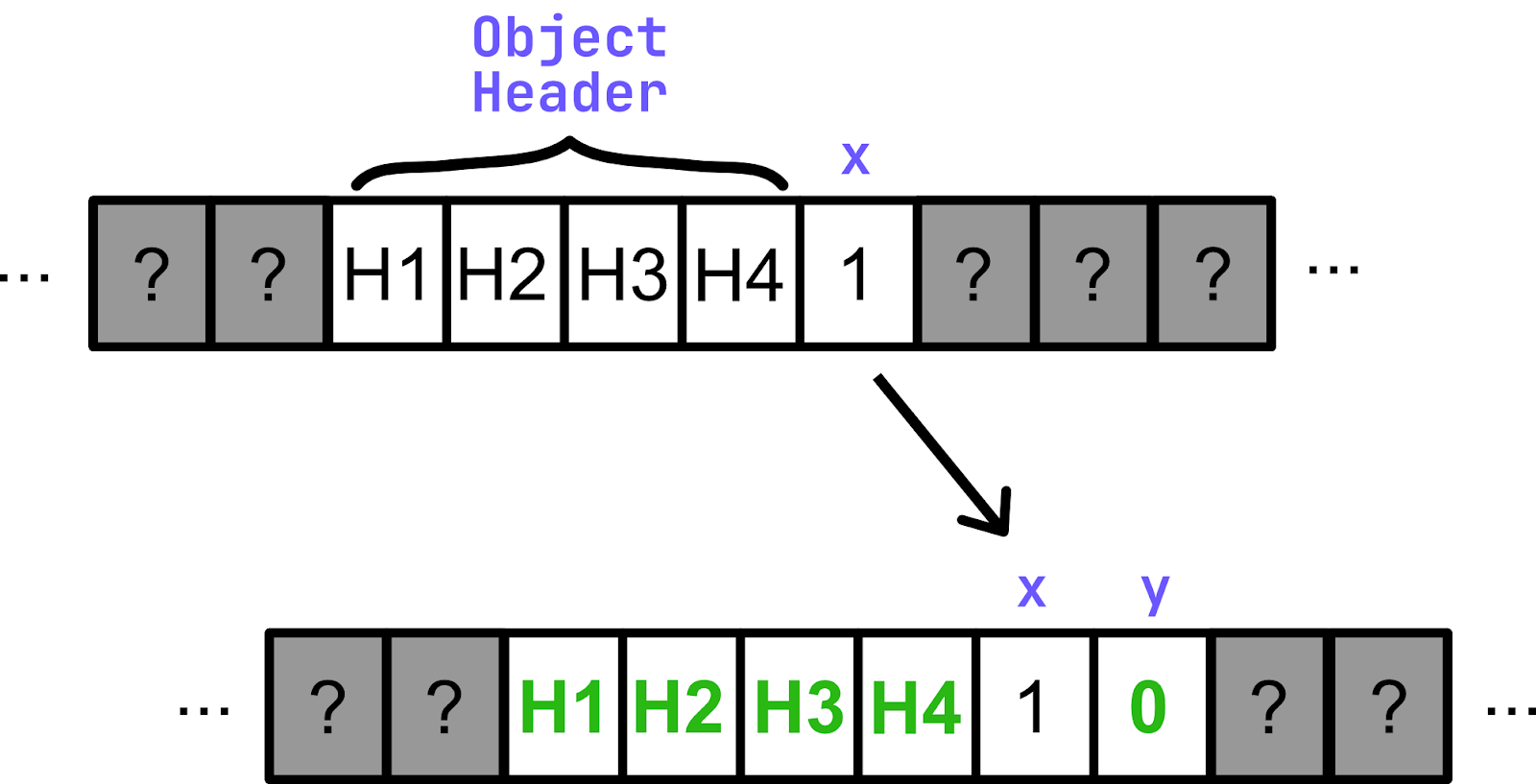

To demonstrate this for the previous example, we can look at the instance created by val foo = Foo(1). The actual instance might look something like this in your memory:

This is where the object currently resides at a known memory location. The memory representation of our object starts with a 16-byte header containing metadata about our object, for example, a pointer or a compressed pointer to our runtime representation of the class (called Klass). Right after the header, we can find the actual fields stored in the object. In our case, we see the value 1 associated with the property x. Memory before or after our object is unknown and could contain basically anything. When a reload changes a class’s layout by adding or removing properties, it becomes clear that the object needs to be adjusted.

This is where the nature of GC works well for migrating the object. GC can allocate a new block of memory to account for the object’s new size, and then start migrating the object by copying its previous values. In the chosen example, we added one more int field, requiring us to allocate 32 additional bits of memory. Since the x field was unchanged, we can just copy the previous value to its new location. However, a decision has to be made on how to treat the newly introduced field y. Re-running the constructor is not feasible, so DCEVM uses the JVM defaults: null, 0, and false.

Note that the new object has a different header that points to the new Klass object, representing the reloaded code.

Once all objects are migrated, all pointers to them will be updated to point to the migrated objects. In our example above, the instance Foo has moved to a new memory location and now carries a y property.

Before we can resume the application, the runtime needs to consider that previous optimizations and just-in-time compilations to machine code might be invalid. For this reason, the code is then “de-optimized”. Once the application resumes, the JIT compiler is free to kick in again, optimizing our code and returning the application to the previous level of performance.

Java agents FTW

DCEVM is an amazing technology that allows you to dynamically reload and redefine code while it is executing. However, to make it actually work, we need a way to call its APIs from the user application.

Luckily, the JVM has a way to implement that – it’s called a Java agent. A Java agent is a Java library that can be attached to any Java program and execute code before the target program starts.

To create a Java agent, we need to declare a class with a premain method. This method, as the name suggests, will be executed before the target application’s main, i.e. during JVM startup. The method takes a String argument and an instance of java.lang.instrument.Instrumentation as its parameters.

fun premain(args: String, instrumentation: Instrumentation)

java.lang.instrument.Instrumentation is a part of the Java Instrumentation API, which allows agents to observe, modify, and redefine classes at runtime. When you are using the JetBrains Runtime, java.lang.instrument.Instrumentation provides you with access to DCEVM via its redefineClasses method implementation.

So, in the case of Compose Hot Reload, the Java agent’s function is relatively straightforward: We attach it to the target application and launch a background task/thread in the premain. This background task will invoke instrumentation.redefineClasses with new classes whenever it receives information about changes to the application’s code.

Finally, we just need to package our agent as a standalone JAR and give the agent information required by the JVM in the manifest file:

Premain-Class: org.jetbrains.compose.reload.agent.ComposeHotReloadAgent

Can-Redefine-Classes: true // declare that we intend to redefine classes

In practice, we use the Compose Hot Reload agent for much more than just redefining classes via DCEVM. We will cover its other functions in the following sections.

You may have noticed that we boldly skipped one of the most important parts of any hot reload by simply claiming that the agent “receives information about changes in the code”. It is, indeed, not so simple. However, to get the whole picture, we first have to dive into another complex subsystem of Compose Hot Reload – its integration with build systems.

Building a zero-configuration tool

The combination of the JetBrains Runtime’s ability to reload code and an agent that can listen for reload requests form the core functionality of Compose Hot Reload. Integrating these components into a zero-configuration product requires careful integration into build tools. The following describes how the Gradle plugin is implemented, but hot reload is also available in Amper. The user-facing workflows can be separated into two typical kinds of builds: In the first, the user compiles the application and intends to launch it in hot-reload mode. In the second kind of build, there will be multiple reloads. These consist of incrementally compiling the code, and then sending the reload request to the agent after a given change. Reload requests typically contain all .class files that have been either changed, added, or modified. While reloading can be triggered manually, it is typically managed either by Compose Hot Reload itself or by the IDE, which watches source files for changes.

This leads to two questions:

- How can the set of changed files be resolved efficiently when reloading?

- How can other tools reliably issue reloads?

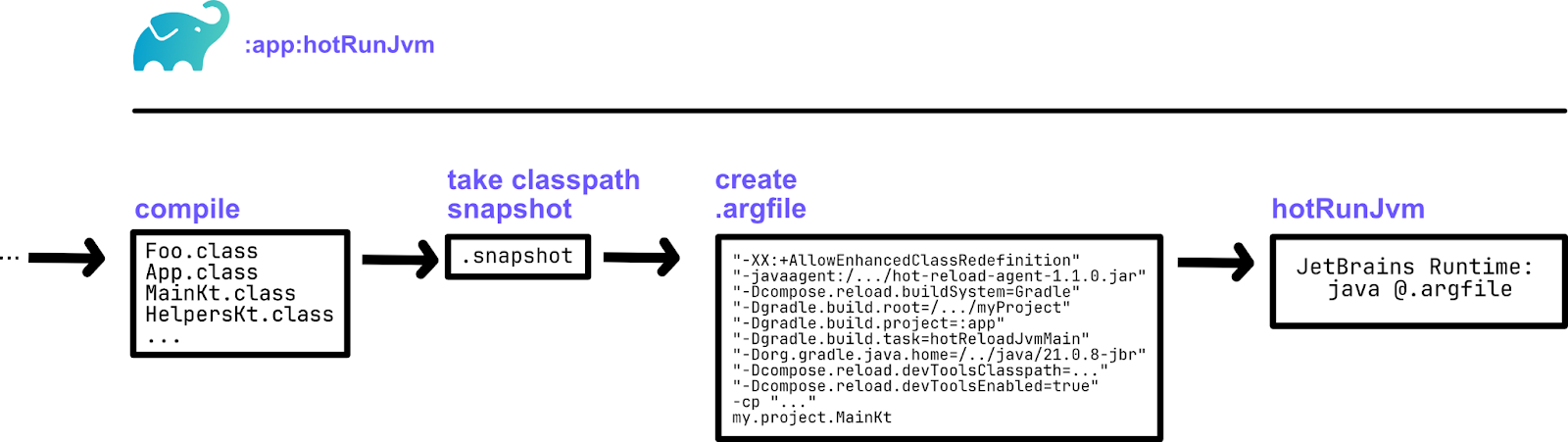

The flow of launching the application already gives a lot of insights into how the overall system works, and it is relatively straightforward:

The entire project is compiled, as usual, and produces the corresponding .class files. Typically, applications can launch directly afterwards by launching the JVM with all necessary arguments (classpath, properties, JVM arguments, user arguments, etc.). A hot reload run will then perform two additional steps before actually launching.

After the compilation finishes, a snapshot of the classpath is taken. It’s worth mentioning that Compose Hot Reload differentiates the classpath into a hot and cold part. Dependencies resolved from remote repositories are considered cold because they won’t change during a hot reload session. Code compiled by the current build, however, is considered hot. The snapshot is therefore only taken of the hot part of the classpath and contains all known .class files, each with a checksum of its contents.

The second task performed by hot reload is to produce special hot-reload arguments for the run. For convenience and to support restarting the application, these arguments will be stored in an .argfile. The most important arguments being:

-XX:+AllowEnhancedClassRedefinition, which enables the JetBrains Runtime’s DCEVM capabilities.-javaagent:/.../hot-reload-agent-1.1.0.jar, which adds our agent to the application.-Dcompose.reload.buildSystem=Gradle, which tells Compose Hot Reload to use the Gradle recompiler backend.-Dgradle.build.root=/.../myProject, which tells Compose Hot Reload where the current Gradle project is located.-Dgradle.build.project=:app, which indicates which Gradle project was launched for hot reload.-Dgradle.build.task=hotReloadJvmMain, which tells Compose Hot Reload which Gradle task can be executed to issue a reload.-Dcompose.reload.devToolsClasspath=..., which provides the floating toolbar application classpath.-Dcompose.reload.devToolsEnabled=true, which enables the floating toolbar application.

Given that the application now has all the information necessary to start reloads by invoking the provided Gradle task at the provided location, Compose Hot Reload will start a supervisor process called devTools. This is the same process that will then provide the floating toolbar window. This process will either start a continuous Gradle build for reloading or wait for external events (such as you clicking Reload, or the IDE sending a signal to reload).

Such signals can be sent through the orchestration protocol, which we’ll talk about in more detail later. For now, it is just essential to know that the application will host a TCP server that allows components, such as Gradle, Amper, or the IDE, to communicate with each other.

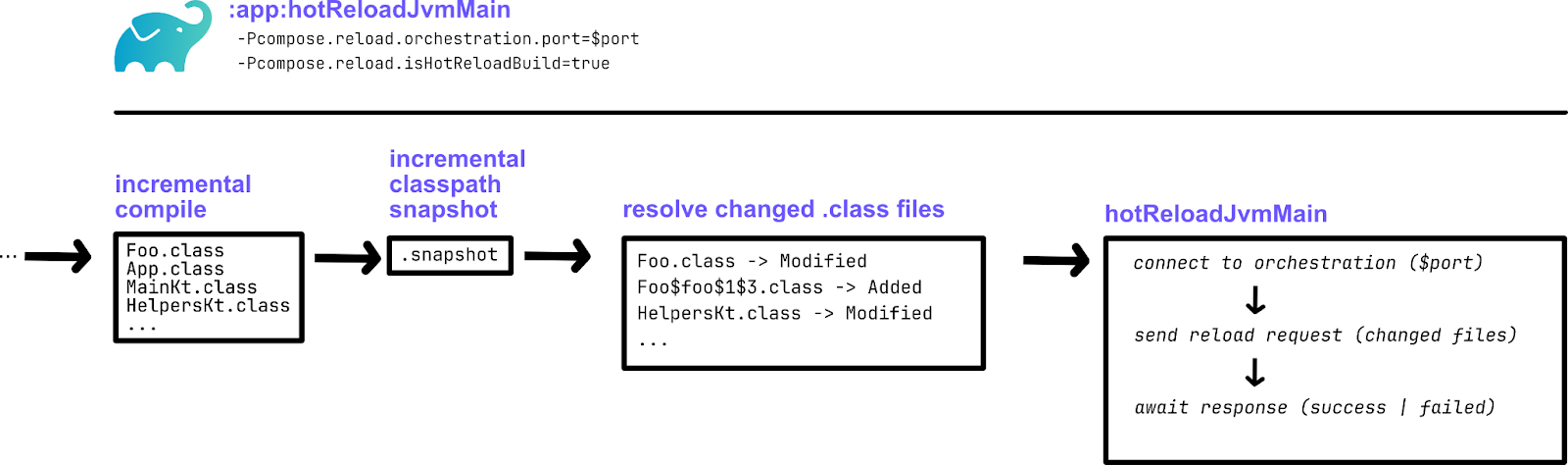

Requests to reload the application will trigger the corresponding reload task. Such a Gradle invocation will be marked as isHotReloadBuild and will get the application server port forwarded as orchestration.port.

Once the project is compiled incrementally, the snapshot will be rebuilt incrementally as well. Comparing the previous snapshot to the new one is quick and produces a map of .class files that are either added, removed, or modified.

The last task is to connect to the application using the provided port and send a request to reload those files. The agent will handle this request and reload the code using the JetBrains Runtime.

Since all relevant tasks can be created automatically by inferring them from the Kotlin Gradle Plugin model, the tool can be used effectively without any further configuration. Launching from the CLI only requires calling the corresponding hotRunJvm task. IntelliJ IDEA can import hot reload tasks during the Gradle sync process and create corresponding run gutters.

But what about the UI?

As we mentioned before, being able to reload the code does not guarantee that Compose Hot Reload will magically start working. Modern applications are far too complex for that to happen. Therefore, after reloading the code, we need to propagate those updates throughout the application, re-rendering the UI, resetting the state, cleaning the references to the old code, etc.

Now, to do that correctly, we first need to understand how Compose code actually works. Let’s take a look at how our App function from the previous examples is represented.

@Composable

fun App() {

var clicks by remember { mutableStateOf(0) }

MaterialTheme {

Column(

horizontalAlignment = Alignment.CenterHorizontally,

) {

Button(onClick = { clicks++ }) {

Text("Clicks: $clicks")

}

Icon(

imageResource(Res.drawable.Kodee_Assets_Digital_Kodee_greeting),

contentDescription = "Kodee!!!",

modifier = Modifier,

tint = Color.Unspecified

)

}

}

}

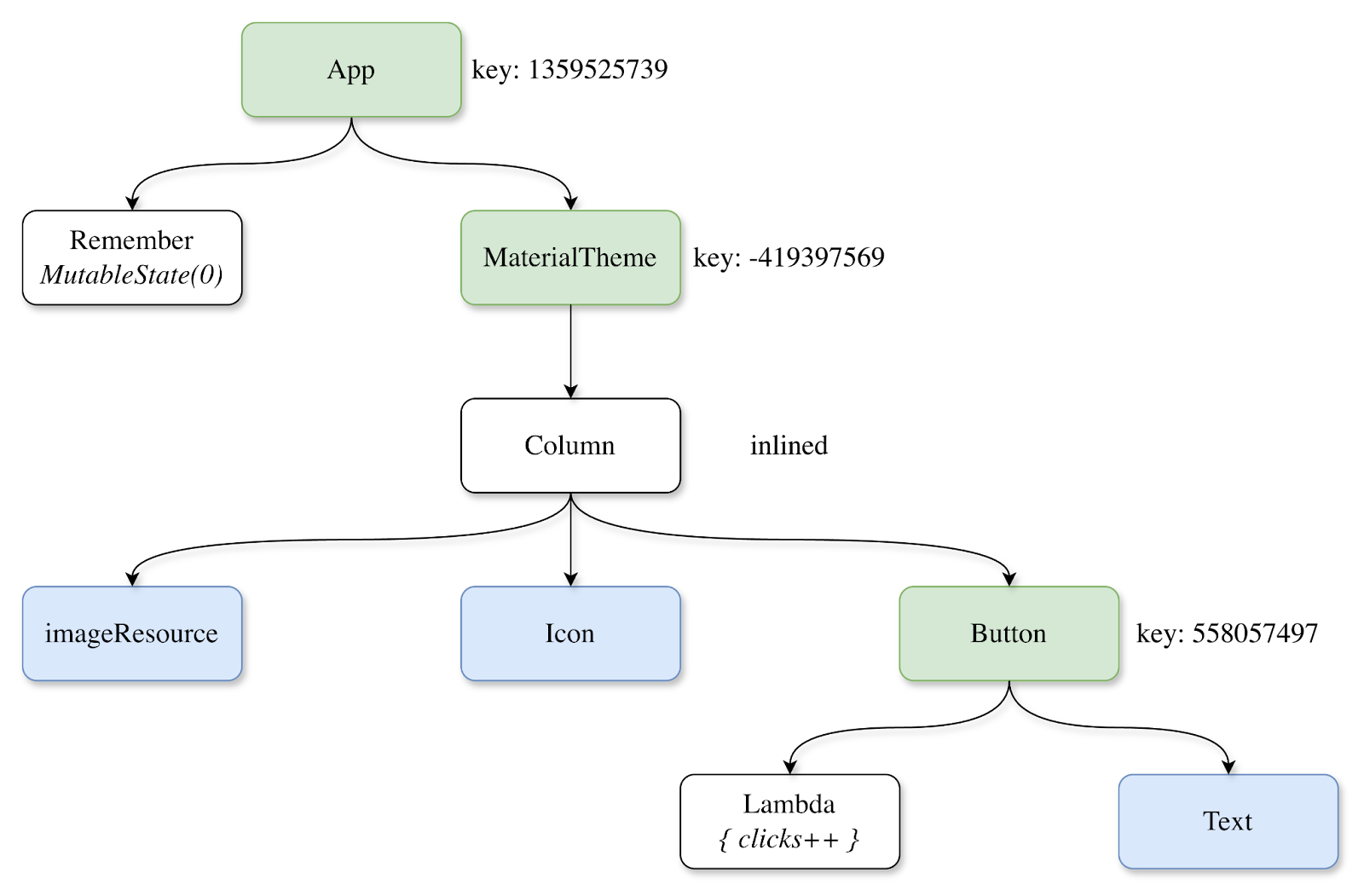

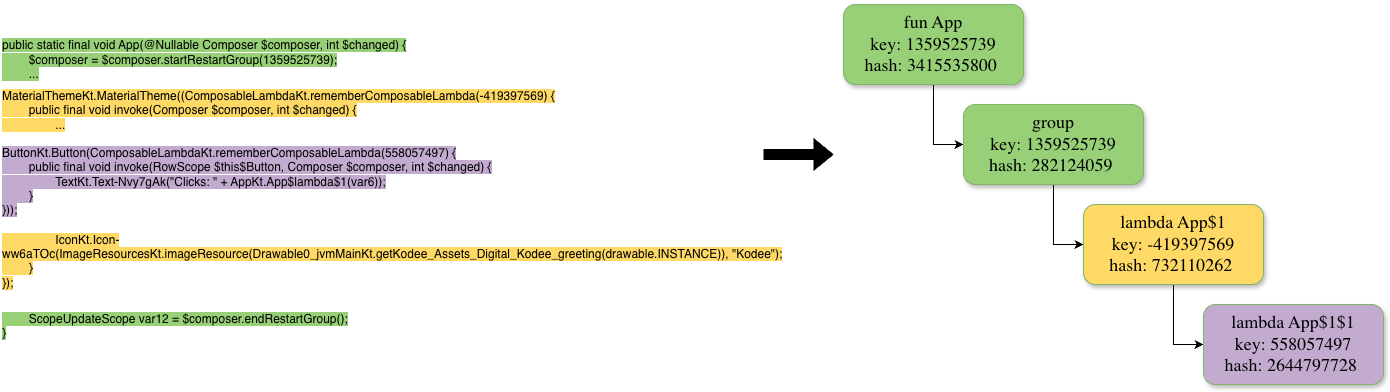

Compose splits the code into sections called groups and assigns each group a unique integer key. As an approximation, you can think that each scope (e.g. each {} pair in the code) corresponds to a separate group. The groups are organized in a tree-like structure that corresponds to their relations in the source code. In this image, green nodes correspond to Compose groups created by the App function, blue nodes represent other Composable functions called in the App function, and white nodes represent state information.

When the Compose Runtime detects that some parts of the UI need to be re-rendered, it marks the groups corresponding to those components as invalid. It then re-executes all the code corresponding to those groups, creating an updated version of the tree. Subsequently, this means that the state created by any invalidated groups will be reset. For example, if we invalidate the group with the key -419397569, the mutable state with the counter will not be reset, while all the other code will be re-executed.

Now that we have a high-level understanding of the Compose representation, how do we actually implement hot reload? Well, the intuitive option would be to reuse the Compose Runtime’s existing functionality: If the code changes, we invalidate all groups corresponding to that code. This will allow us to:

- Re-render only the necessary parts of the UI.

- Preserve the state whenever possible.

- Clean up all references to the old code.

To do that, we need to understand:

- What code has been changed?

- Which Compose groups need to be invalidated because of that change?

And here, the Compose Hot Reload agent comes into play one more time.

Bytecode analysis

When compiling the application, the Compose plugin changes the intermediate representation (IR) of the Composable functions and inserts additional instructions for the Compose Runtime. For example, the bytecode of the App function will start with the following instruction: $composer.startRestartGroup(1359525739).

Here, startRestartGroup is a special instruction of the Compose Runtime that marks the start of a new group, and its argument is the key for this group. Correspondingly, the end of this group will be marked by a call to endRestartGroup. This means that all the information that we’re interested in is actually contained in the bytecode; we just need to extract it.

Luckily, the Java agent allows us to hook into the target application and inspect all the classes while they are loading. We use the ASM library to analyze classes, and for each method, we build our own representation of the Compose tree. By locating the startGroup and endGroup calls, we can determine the bounds (and keys) of Compose groups, and their locations in the code define the parent-child relations between them. Conditional branches inside a function can be parsed by tracking jump instructions and their target labels.

For each Compose group, we determine its key, its relations with other groups, its dependencies on different methods, and its hash. The group’s hash value attempts to capture its semantics; for simplicity, we can think of it as a hash of all the bytecode instructions in this group. It allows us to quickly determine whether the group’s code has changed semantically during reloads.

Tracking changes

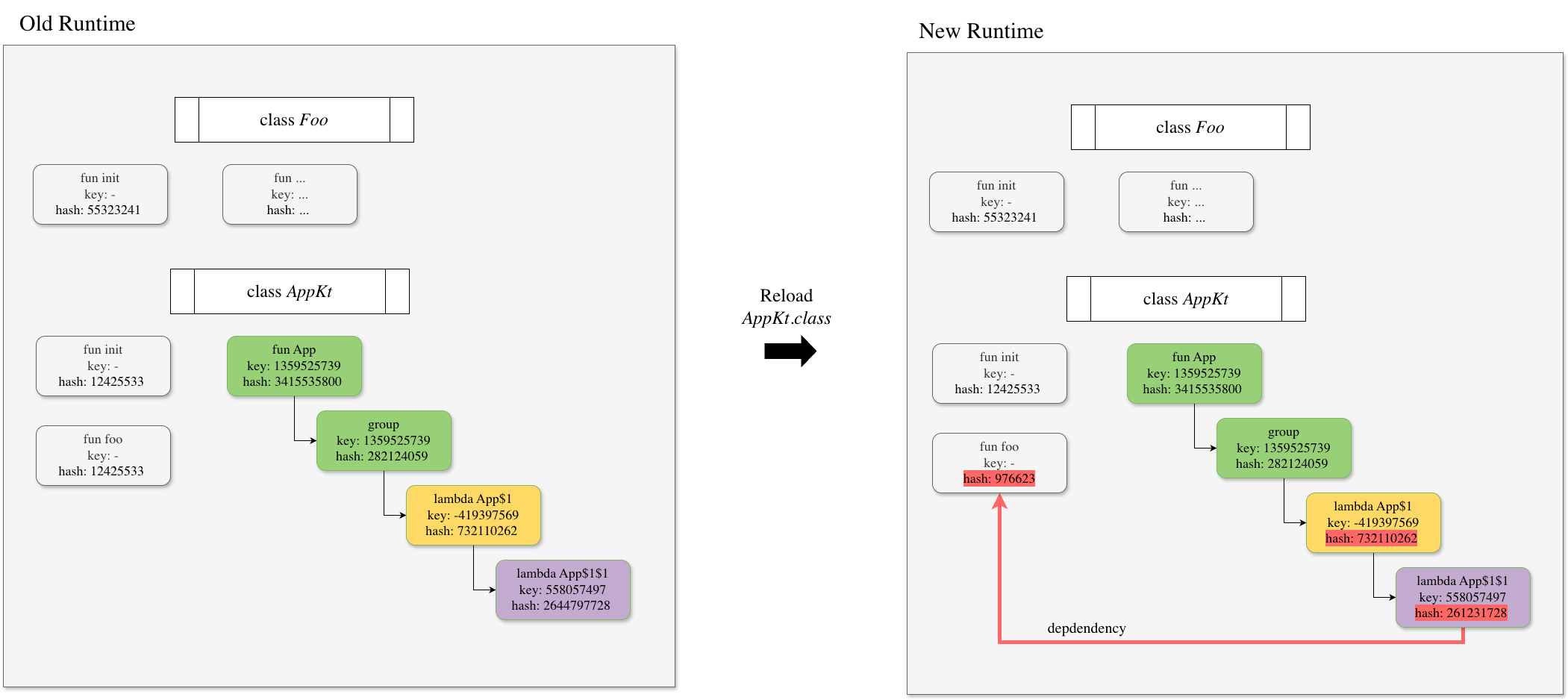

Now that we know how to extract information from the bytecode, we need to think about how to apply it. As we mentioned, a Java agent allows us to analyze every class before it has been loaded. This will enable us to analyze classes not only during initial loading, but also during reloads. Thus, during reload, we can keep track of both the old and new versions of each class and monitor changes.

When the class is reloaded, we can compare both its old and new runtime information and invalidate groups using the following rules.

- If the code hash of a Compose group is changed, invalidate it.

- If the code hash of a non-Compose function is changed, invalidate all Compose groups that are (transitively) dependent on it. Since we keep track of the entire runtime, we can efficiently compute all method dependencies.

After that, the only thing left to do is to save the new version of the runtime as the current one.

The compiler doesn’t like your hot reload stuff

Even though the core idea of the code invalidation and UI re-rendering approach is not particularly complicated, the path to Compose Hot Reload’s success was blocked by many obstacles and hurdles we had to overcome. Many of them stemmed from the fact that the Kotlin compiler and Compose plugin weren’t built with DCEVM and hot swapping in mind. Therefore, bytecode produced by those tools often behaved unexpectedly during hot reload. In this section, we will highlight some of the technical difficulties we encountered during the development of Compose Hot Reload and how we solved them.

All your lambdas belong to us

Both Kotlin and Compose encourage heavy use of lambda functions. However, lambda functions were a significant source of inconsistency in the bytecode produced by the Kotlin compiler, mainly due to their names. Users do not provide names for lambda functions; therefore, the compiler generates them itself, using predefined rules to determine each lambda’s name. Unfortunately, those rules are not designed with hot reload in mind.

There are two ways a lambda function can be compiled to the bytecode: anonymous classes and indy lambdas. The first way suggests that a lambda is compiled as a class that implements one of Kotlin’s FunctionN interfaces, and the lambda’s body is placed inside the invoke method of this class.

The indy way suggests that a lambda is compiled as a function inside the original class, which is then converted into an object in the runtime via the JVM’s invokedynamic instruction and the LambdaMetafactory.

fun bar() =

foo { println(it) }

fun foo(a: (Int) -> Unit) {

listOf(1, 2, 3).forEach(a)

}

Class-based lambda:

final class org/example/project/MainKt$bar$1 extends kotlin/jvm/internal/Lambda implements kotlin/jvm/functions/Function1 {

// access flags 0x0

<init>()V

L0

ALOAD 0

ICONST_1

INVOKESPECIAL kotlin/jvm/internal/Lambda.<init> (I)V

RETURN

// access flags 0x11

public final invoke(I)V

GETSTATIC java/lang/System.out : Ljava/io/PrintStream;

ILOAD 1

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/io/PrintStream.println (I)V

RETURN

}

Indy lambda:

public final static bar()V INVOKEDYNAMIC invoke()Lkotlin/jvm/functions/Function1; [ // handle kind 0x6 : INVOKESTATIC java/lang/invoke/LambdaMetafactory.metafactory(Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodHandles$Lookup;Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodType;Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodType;Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodHandle;Ljava/lang/invoke/MethodType;)Ljava/lang/invoke/CallSite; // arguments: (Ljava/lang/Object;)Ljava/lang/Object;, // handle kind 0x6 : INVOKESTATIC org/example/project/MainKt.bar$lambda$0(I)Lkotlin/Unit;, (Ljava/lang/Integer;)Lkotlin/Unit; ] INVOKESTATIC org/example/project/MainKt.foo (Lkotlin/jvm/functions/Function1;)V RETURN private final static bar$lambda$0(I)Lkotlin/Unit; GETSTATIC java/lang/System.out : Ljava/io/PrintStream; ILOAD 0 INVOKEVIRTUAL java/io/PrintStream.println (I)V GETSTATIC kotlin/Unit.INSTANCE : Lkotlin/Unit; ARETURN

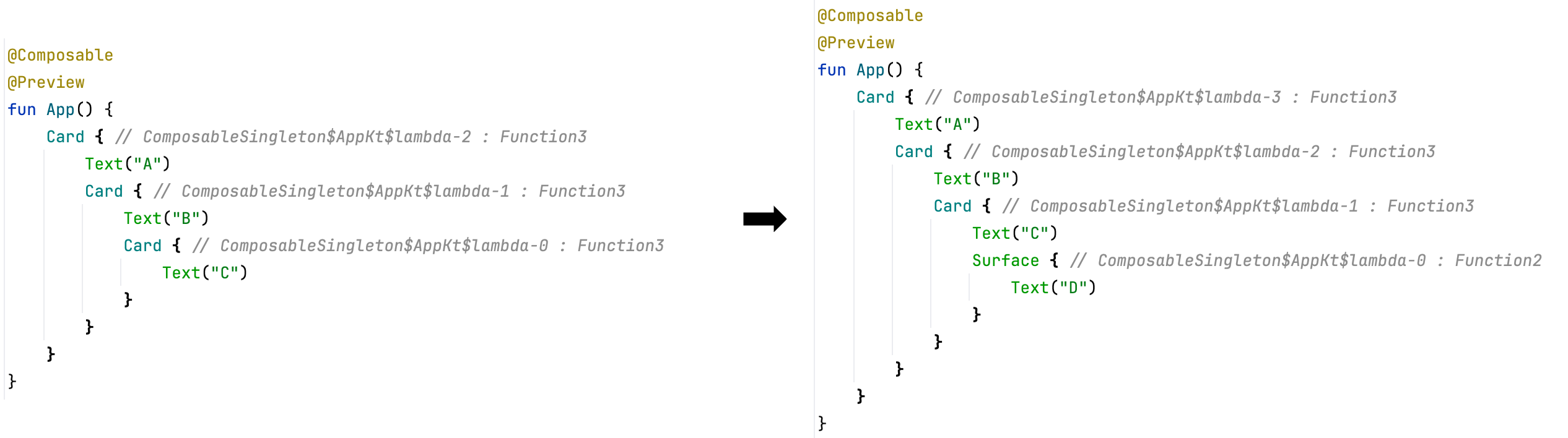

ComposableSingleton classes

Compose attempts to emit every composable lambda function as a singleton, meaning there is only one instance of that lambda function in existence. Therefore, it compiles all the composable lambdas as classes with a ComposableSingleton prefix in their names. Before Kotlin 2.1.20, the Compose compiler traversed nested functions using depth-first search and assigned each lambda class a unique name just using a counter.

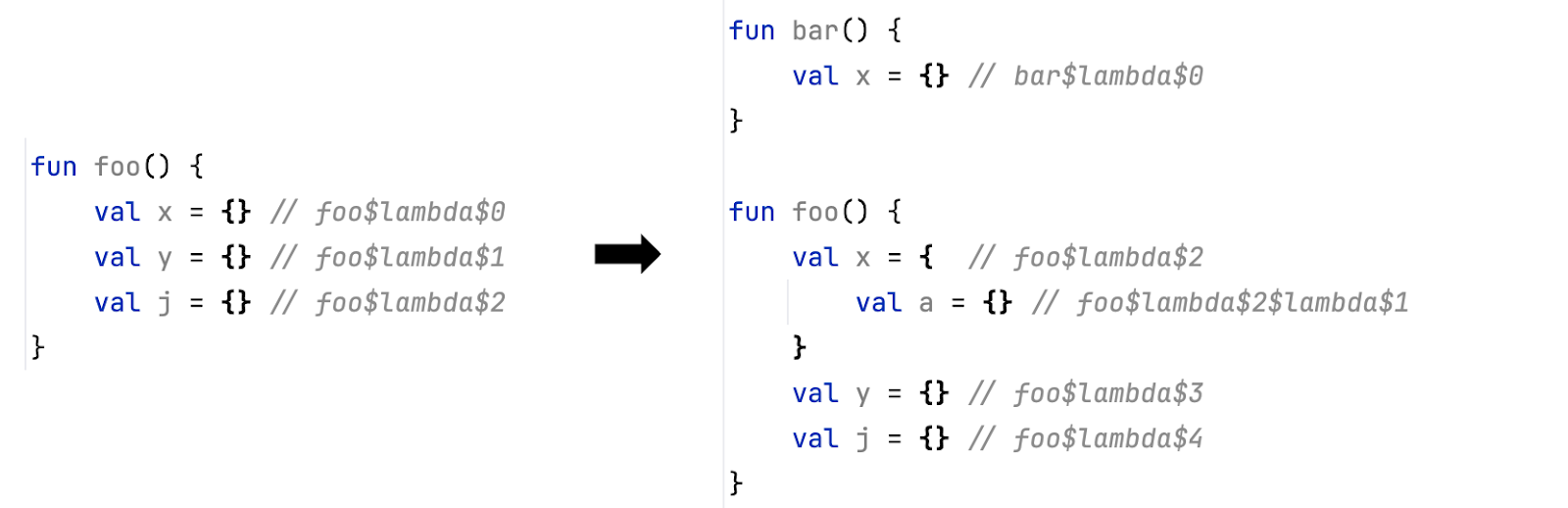

The problem, however, arises when we introduce changes to the original code:

As you can see, just by adding a single new call to Surface, we caused two significant changes:

- Each lambda class changed, because adding a new lambda at the bottom of the tree caused all the lambda classes in the file to be renamed.

- The class named

ComposableSingleton$AppKt$lambda-0changed its interface fromFunction3toFunction2, which causes an error in the JetBrains Runtime during reload, as before version 21.0.8, the JetBrains Runtime did not support changes to class interfaces.

Obviously, these kinds of dramatic bytecode changes are not good when hot reloading. Therefore, we changed how the Compose compiler generates names for composable singleton lambdas. Starting from version 2.1.20, the Compose compiler uses group keys as a stable, unique name for composable lambdas:

This change ensures that changes to composable lambdas do not cause errors or excessive invalidations in Compose Hot Reload.

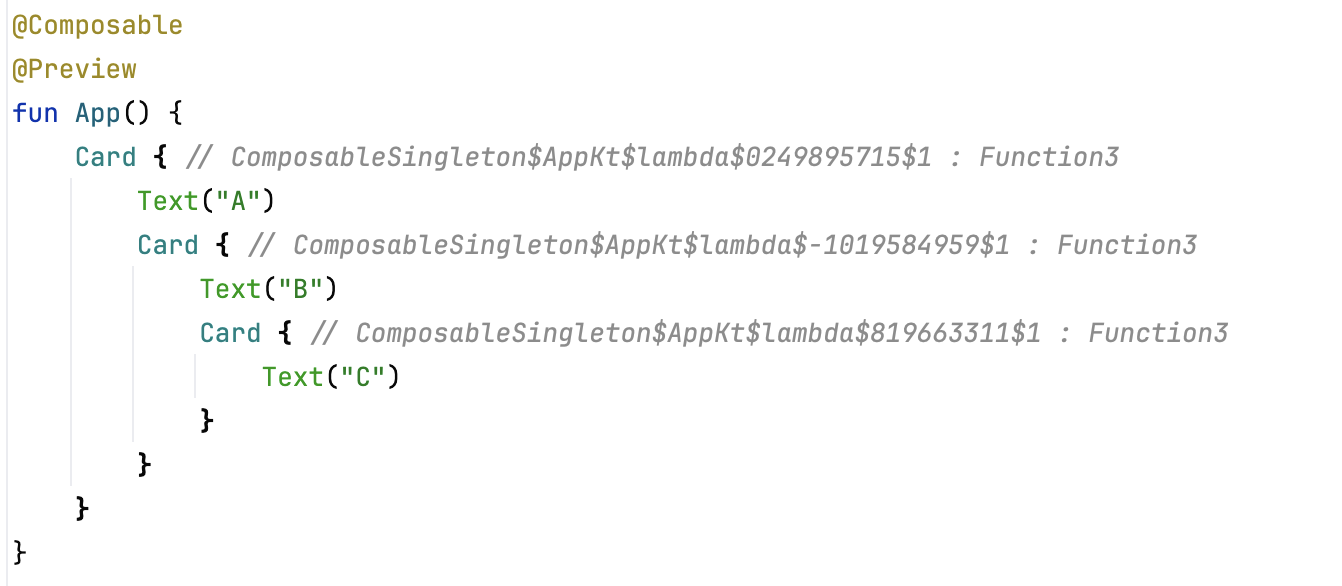

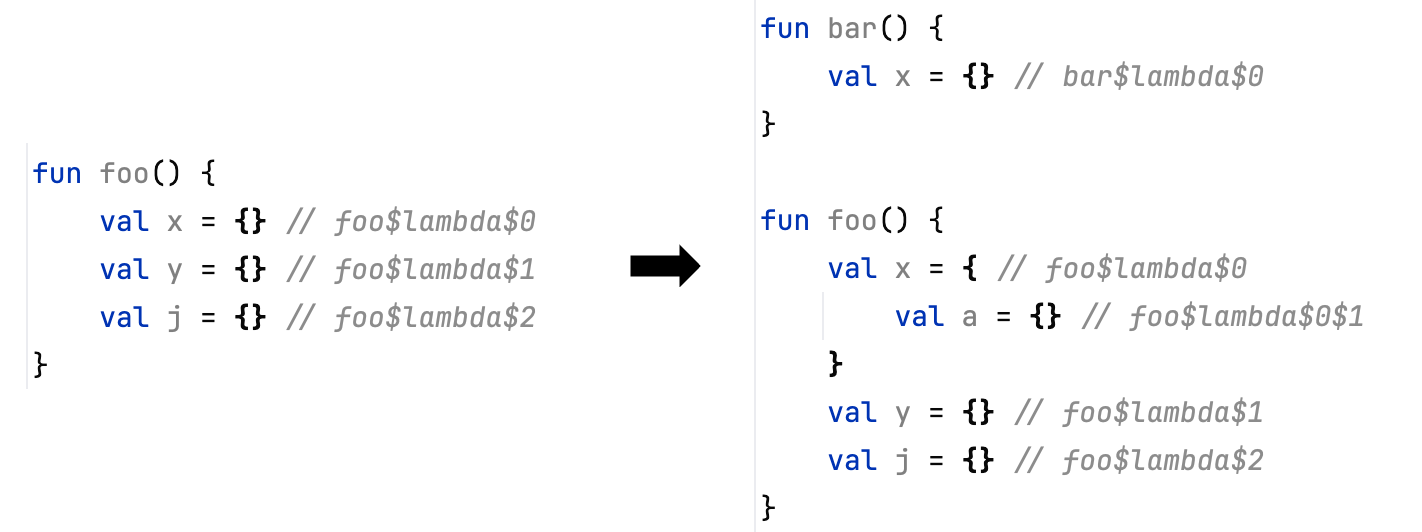

Indy lambdas

We encountered similar problems with the names generated for indy lambdas by the Kotlin compiler: Adding a nested lambda anywhere in the code renames all other lambdas.

This issue leads to the same problems as we observed with ComposableSingletons. However, this issue was reinforced by the fact that it affects all lambdas in the code, and Kotlin switched to indy lambdas by default in 2.0.0.

To solve this problem, we have changed the Kotlin compiler. As of Kotlin 2.2.20, indices for indy lambda names are unique for each scope they appear in. This guarantees that:

- Random changes at the beginning of the file will not affect lambda names at the end of the file.

- Adding nested lambdas will not affect all the other lambdas declared in the class.

FunctionKeyMeta annotations

The whole functionality of Compose Hot Reload relies on the fact that we can extract information about Compose from the bytecode. However, consider this example:

@Composable

fun App() {

Button(onClick = { }) {

Text("Click me!!!")

}

}

The lambda, passed to a Button call, only creates a single text field and does not create any new Compose groups. The (decompiled) bytecode of this lambda function looks like this:

final class ComposableSingletons$AppKt$lambda$-794152384$1 implements Function3<RowScope, Composer, Integer, Unit> {

@FunctionKeyMeta(

key = -794152384,

startOffset = 568,

endOffset = 603

)

@Composable

public final void invoke(RowScope $this$Button, Composer $composer, int $changed) {

Intrinsics.checkNotNullParameter($this$Button, "$this$Button");

ComposerKt.sourceInformation($composer, "C17@578L19:App.kt");

if ($composer.shouldExecute(($changed & 17) != 16, $changed & 1)) {

if (ComposerKt.isTraceInProgress()) {

ComposerKt.traceEventStart(-794152384, $changed, -1, "ComposableSingletons$AppKt.lambda$-794152384.<anonymous> (App.kt:17)");

}

TextKt.Text--4IGK_g("Click me!!!", (Modifier)null, 0L, 0L, (FontStyle)null, (FontWeight)null, (FontFamily)null, 0L, (TextDecoration)null, (TextAlign)null, 0L, 0, false, 0, 0, (Function1)null, (TextStyle)null, $composer, 6, 0, 131070);

if (ComposerKt.isTraceInProgress()) {

ComposerKt.traceEventEnd();

}

} else {

$composer.skipToGroupEnd();

}

}

}

As you may notice, the source code of the invoke function does not contain any calls to startGroup or endGroup methods, and we can’t reliably extract the group information from it. The only way to access it is to read the FunctionKeyMeta annotation. This is a special annotation emitted by the Compose compiler that is intended to be used by tooling.

However, before version 2.1.20, there was no way to generate FunctionKeyMeta annotations on composable functions, and there was no way to infer the group key from the bytecode of the compiled composable lambdas. We introduced this option in Kotlin 2.1.20 (which is why it is the required version of Kotlin if you want to use Compose Hot Reload) and enabled it by default in Kotlin 2.2.0.

Lifting the limits of the JetBrains Runtime

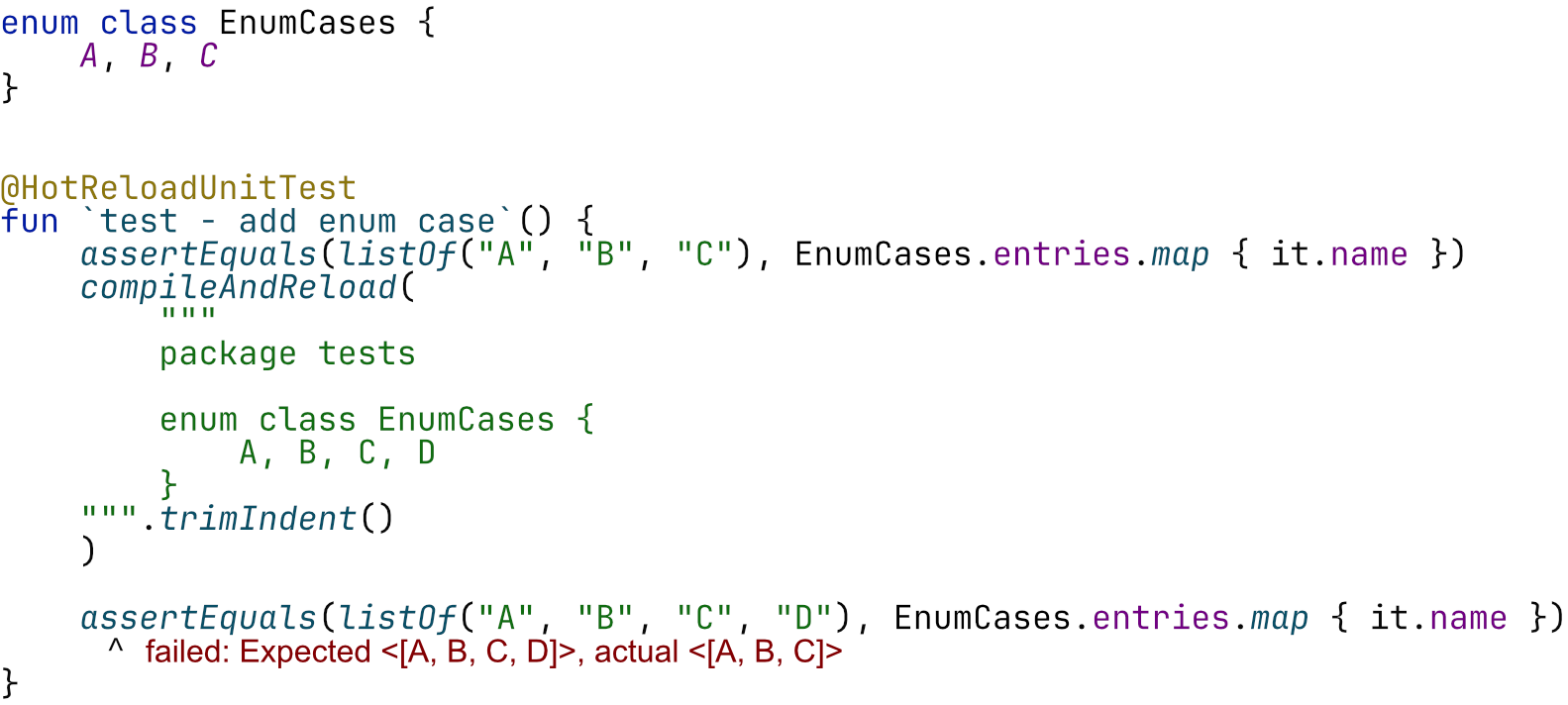

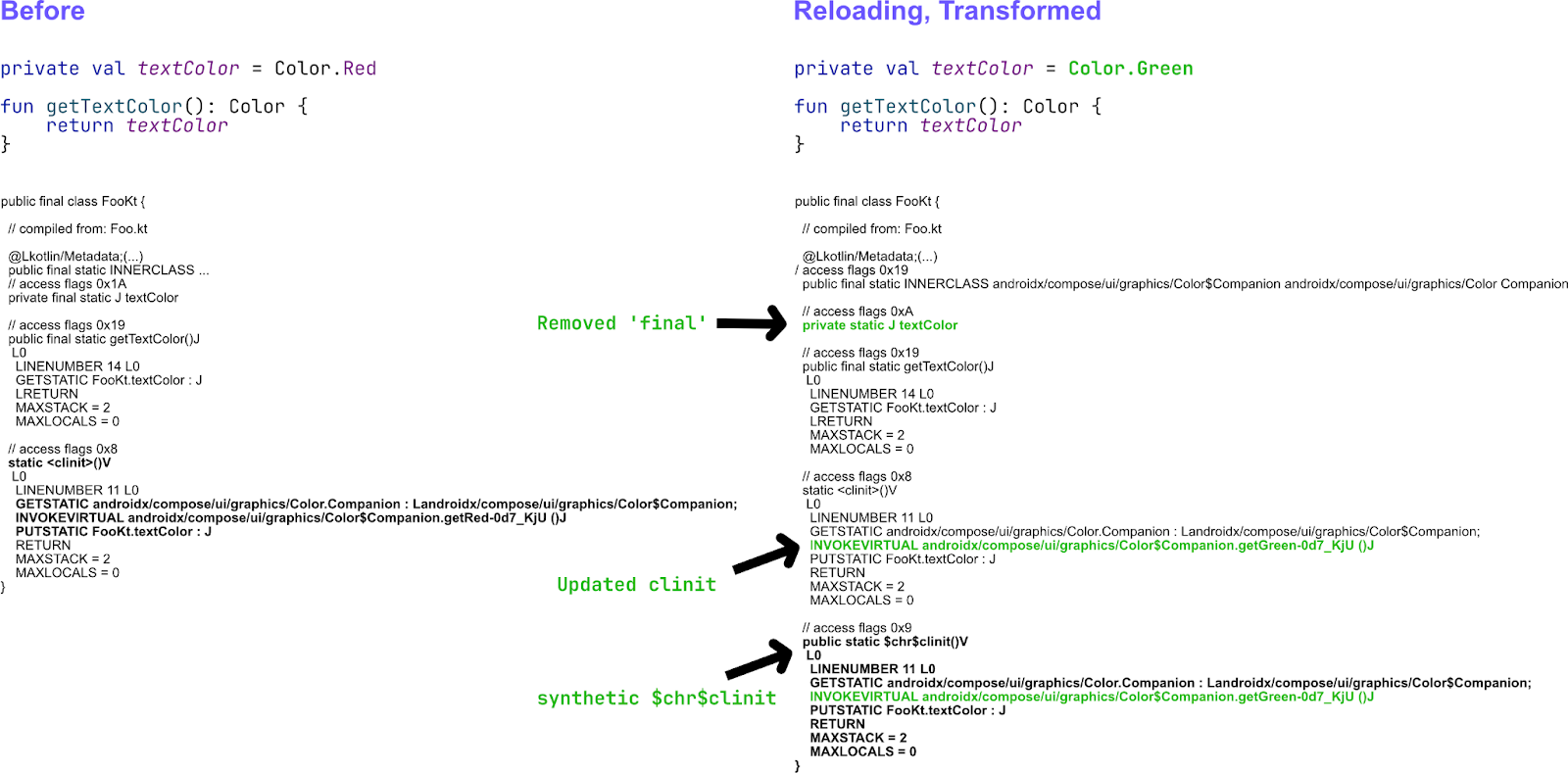

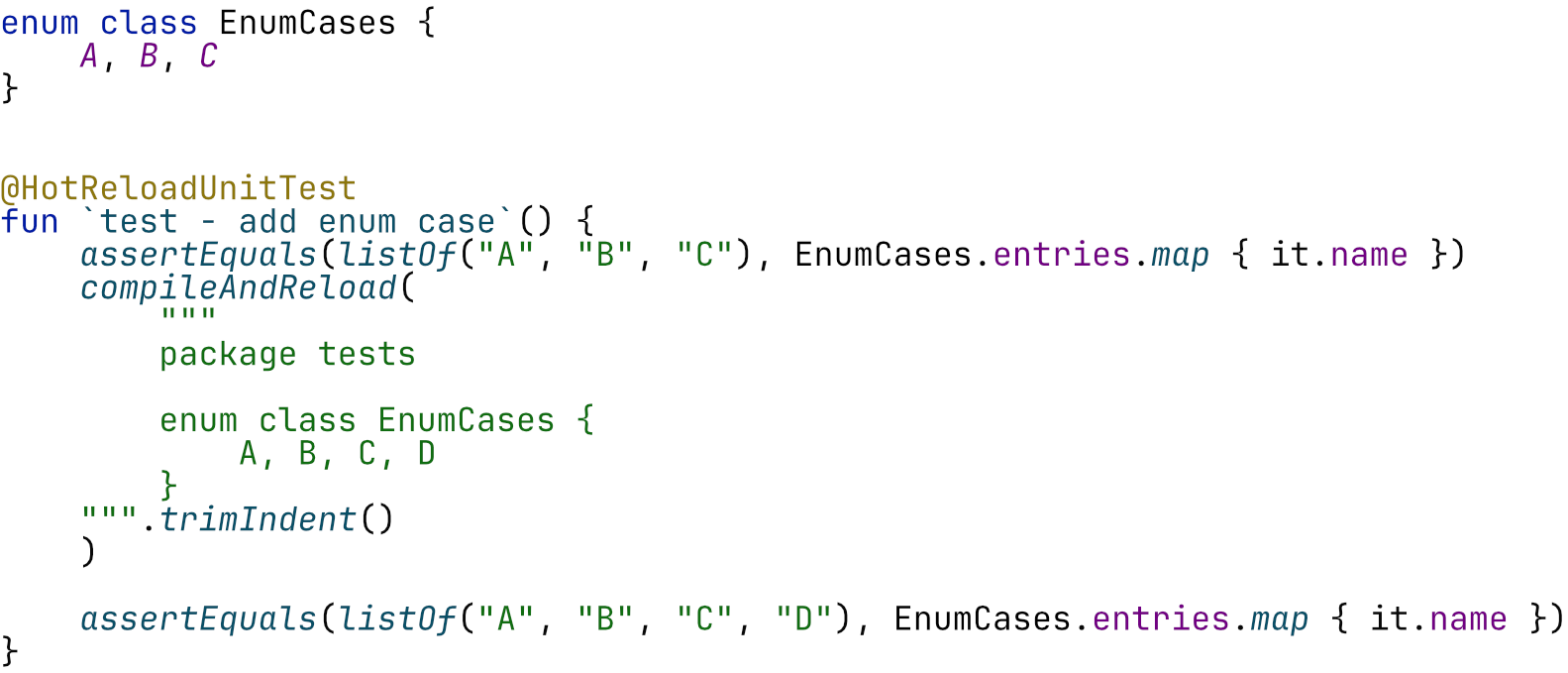

With the compiler tamed to emit bytecode that can be reloaded, another set of potential issues needs to be solved. One such issue surfaced very early in our testing. What should happen to the state that was statically initialized? The state in question here is not a UI state, stored by Compose, but static values, such as top-level properties. Take a look at the following test, which failed in early versions of Compose Hot Reload.

The test first defines an enum with the cases A, B, and C, then compiles and reloads the enum definition so that it also contains the case D. This failure is due to the EnumCases.entries being stored statically on the enum class. Once this collection is initialized, reloading this code will not magically cause its state to change to include the new case. Similarly, any other top-level property or static value would not change.

This is analogous to managing the state within the Compose framework, which means the same problems need to be solved.

We still need a way to reinitialize static values, and we need to know when to do so. This time around, we can answer the question of when to do so much more easily: Our bytecode analysis engine is perfectly capable of finding which functions and properties are considered dirty. However, reinitializing static fields is not as straightforward as calling a function. First, many static fields are also declared as final; re-assigning values cannot be done by calling a given function again, as it would require reflection. Second, the code that initializes statics lives inside a function called clinit. This function cannot be simply invoked, as it’s supposed to be invoked during class loading by the JVM itself. The problem requires transforming the code of .class files that will subsequently be reloaded. The transformation removes all final modifiers from static fields and copies the body of the clinit function to a new, synthetic $chr$clinit function (where chr is short for Compose Hot Reload). When reloading, the clinit method of several classes can be marked as dirty. We enqueue those classes for reinitialization and call them in topological order, according to their dependencies.

When this project started, one of the stated limitations of the JetBrains Runtime was that reloads were rejected if either the superclass or any of a class’s interfaces changed while the class had active instances. Since some Kotlin lambdas still compile to abstract classes that implement Function1, Function2, and other interfaces, the limitation prevented some valid user code from reloading. We were able to produce lambda class names that were unique in Compose and much more tame outside of Compose, but users could occasionally encounter this limitation. We’re happy to announce that the team working on the JetBrains Runtime, especially Vladimir Dvorak, has lifted the restriction on changing interfaces and is now working on changing superclasses as well.

The orchestration protocol

We have previously seen that different processes need to communicate with each other. There are two concepts we can deduce from the required communication:

- Events: Single-shot pieces of data (something that happened to which other parts of the system can react).

- States: Current statuses of different Compose Hot Reload components that are continuously updated and available across the entire orchestration. For example, the

ReloadStatecan either beOk,Reloading, orFailed. This is not just a single event, but a universal state that each component can interact with. You can see that thisReloadStatewill be displayed in the application, the floating toolbar, and the IDE.

Typically, such communication patterns can be modelled using higher-level abstractions, such as HTTP, and many would think that Ktor, or kotlinx.rpc might be fitting technologies. We, however, believe that technologies like Compose Hot Reload need to prioritize compatibility over our own developer experience. Using external libraries inside our devtools application is not a problem, but the communication with the user application requires code to run inside the user’s application, and polluting the user’s classpath might lead to frustrating compatibility issues. Shading such libraries can work, but most of those libraries would require kotlinx.coroutines. While kotlinx.coroutines can be shaded, it is designed to be a system-level library, and we would like to keep it this way.

Therefore, we opted to implement all of the server/client code without any external dependencies. To model async code accurately, we even implemented a tiny coroutines runtime that allows launching tasks, switching threads, offering a Queue option (analogous to a Channel in kotlinx.coroutines), and more.

The key aspect of this protocol is that it is both forward- and backwards-compatible. This bi-directional compatibility is verified by running tests in a special way, but we’ll go into more detail on that later.

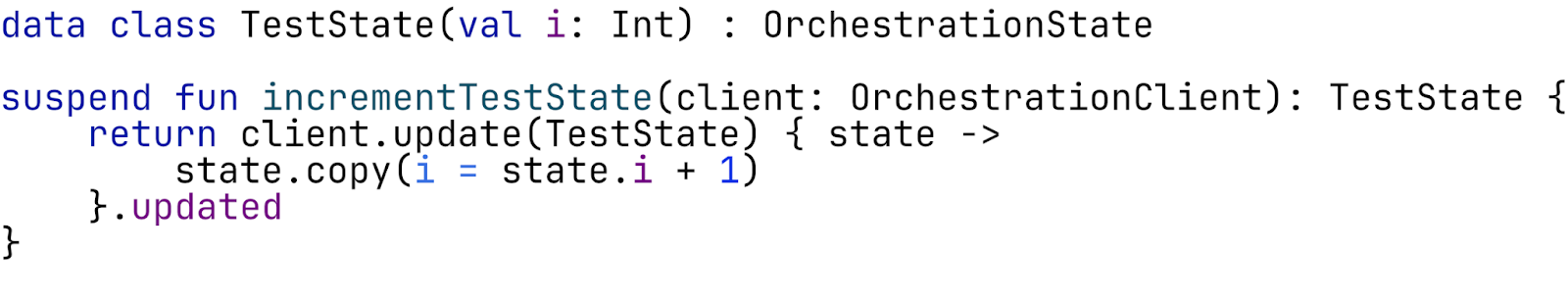

Defining a state within a single process is hard enough to get right, but defining it across multiple processes raises the question of how to implement it safely. State updates in Compose Hot Reload are defined atomically and are done through an atomic update function. This means that racing threads, even racing processes, will be able to conveniently update a given state while using a pattern that is widely adopted by application developers:

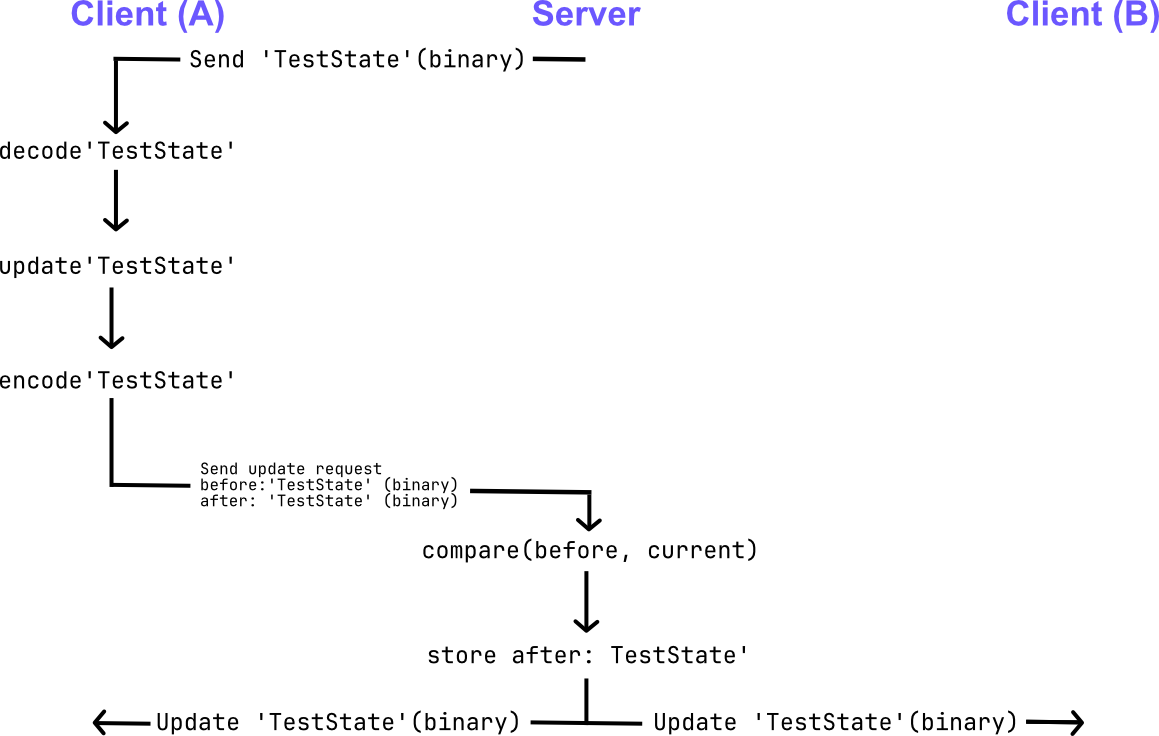

The provided update function ensures atomic updates to the state. Like an AtomicReference or a MutableSharedFlow, this update function might be called multiple times if proposed updates are rejected. To enable such atomic updates across numerous processes, the OrchestrationServer acts as the source of truth: Any participant trying to update the state will send binary Update requests to the server. These requests will contain the binary (serialized) form of the expected state and the binary form of the updated state.

The server processes all requests in a single Queue. If the expected binary matches, the update gets accepted, and the updated state binary is distributed to all clients. If many threads or processes are racing to update a given state value, the expected binary representation might have changed so that it no longer matches the update request. Such updates will be rejected; the client will receive the new underlying state value, call the update function again, and send a new update request.

Fast visual feedback

We’ve now covered the internal workings of Compose Hot Reload. But as interesting as all that is, in our opinion, fast visual feedback is the most important part of the hot reload experience. So, how can we provide this feedback, and more importantly, share it across different processes? Well, the key to doing this is the states that are shared between all processes via the orchestration protocol. The hot-reload-devtooling-api module introduces them:

WindowsState. By hooking into the user application process and intercepting all theComposeWindow.setContentinvocations, we can keep track of all the windows created by the user application. Each window is assigned a uniquewindowId, and we keep information about the current position of all windows.

public class WindowsState(

public val windows: Map<WindowId, WindowState>

) : OrchestrationState {

public class WindowState(

public val x: Int,

public val y: Int,

public val width: Int,

public val height: Int,

public val isAlwaysOnTop: Boolean

)

}

ReloadState.ReloadStatekeeps track of the current reload status. Basically, it tracks all orchestration messages and updates the state based on reload, recompile, or build status messages exchanged between the processes.

public sealed class ReloadState : OrchestrationState {

public abstract val time: Instant

public class Ok(

override val time: Instant,

) : ReloadState()

public class Reloading(

override val time: Instant,

public val reloadRequestId: OrchestrationMessageId?

) : ReloadState() {

public class Failed(

override val time: Instant,

public val reason: String,

) : ReloadState()

}

ReloadCountState. In addition to the reload state, it is also nice to keep track of the history of reload attempts. Working on the UI of your application and seeing that you have iterated on it over 30 times already is a very inspiring feeling!

public class ReloadCountState( public val successfulReloads: Int = 0, public val failedReloads: Int = 0 ) : OrchestrationState

As we mentioned before, all these states are shared between the processes. So if you feel like it, you can actually create your own UI tooling for Compose Hot Reload!

In-app effects

The Compose Hot Reload agent hooks to the user application process and intercepts Compose calls that initialize the window: ComposeWindow.setContent and ComposeDialog.setContent. To be more precise, we don’t just intercept these calls; we actually replace them with our own implementation that wraps the user content into a special DevelopmentEntryPoint function.

@Composable

public fun DevelopmentEntryPoint(

window: Window,

child: @Composable () -> Unit

) {

startWindowManager(window)

val currentHotReloadState by hotReloadState.collectAsState()

CompositionLocalProvider(hotReloadStateLocal provides currentHotReloadState) {

key(currentHotReloadState.key) {

when {

reloadEffectsEnabled -> ReloadEffects(child)

else -> child()

}

}

}

}

This is a very high-level implementation of the DevelopmentEntryPoint. As you can see, it provides us with three key features:

- We start a window manager that updates the

WindowStateof the current window. - We wrap the user app’s contents in a separate scope guarded by a special hot-reload state. If we ever want to reset the user application’s UI state, we can do so by resetting the hot-reload state.

- We wrap the user content into the

ReloadEffectsfunction, which renders all in-app effects based on the shared states.

Floating toolbar

The floating toolbar, or the Compose Hot Reload Dev tools window, is a separate process that starts together with the user application and connects to the orchestration. Then, it just tracks the WindowsState, and launches a new toolbar for each window of the user application. The toolbar just tracks the target window’s state and updates its position accordingly.

The toolbar also contains action buttons that control the user application: Reload UI, Reset UI, and Shutdown. These actions are implemented via the orchestration protocol as well: Clicking a button just triggers a corresponding orchestration message to be sent to all connected processes. Each process then knows how to handle received commands.

IDE integration

IDE support for Compose Hot Reload is implemented in the Kotlin Multiplatform plugin. When you open a Kotlin Multiplatform project in your IDE, the KMP plugin checks whether the Compose Hot Reload plugin is applied to the project. If it is, the KMP plugin also checks the versions for compatibility (IDEs support Compose Hot Reload versions from 1.0.0-beta07 onward). Via IDE integration with the build systems, the KMP plugin can extract all the information needed to run the app in hot-reload mode. And when you click on the Run button in the gutter next to main, the KMP plugin automatically generates a new run configuration with hot reload enabled.

Everything else works very similarly to the Dev tools window. The KMP plugin connects to the orchestration server of the running application and displays information about the app’s current state: logs, reload status, errors, etc.

Testing

This project required the team to think about many components across the entire Kotlin and JetBrains technology stack, and we have spent a lot of time debugging, experimenting, and writing production code. We would like to claim that most of our time was spent on our project infrastructure. However, we estimate that roughly 30% of all our commits were purely for introducing test infrastructure, highlighting how complicated testing a system that reloads code can be.

Hot-reload unit tests

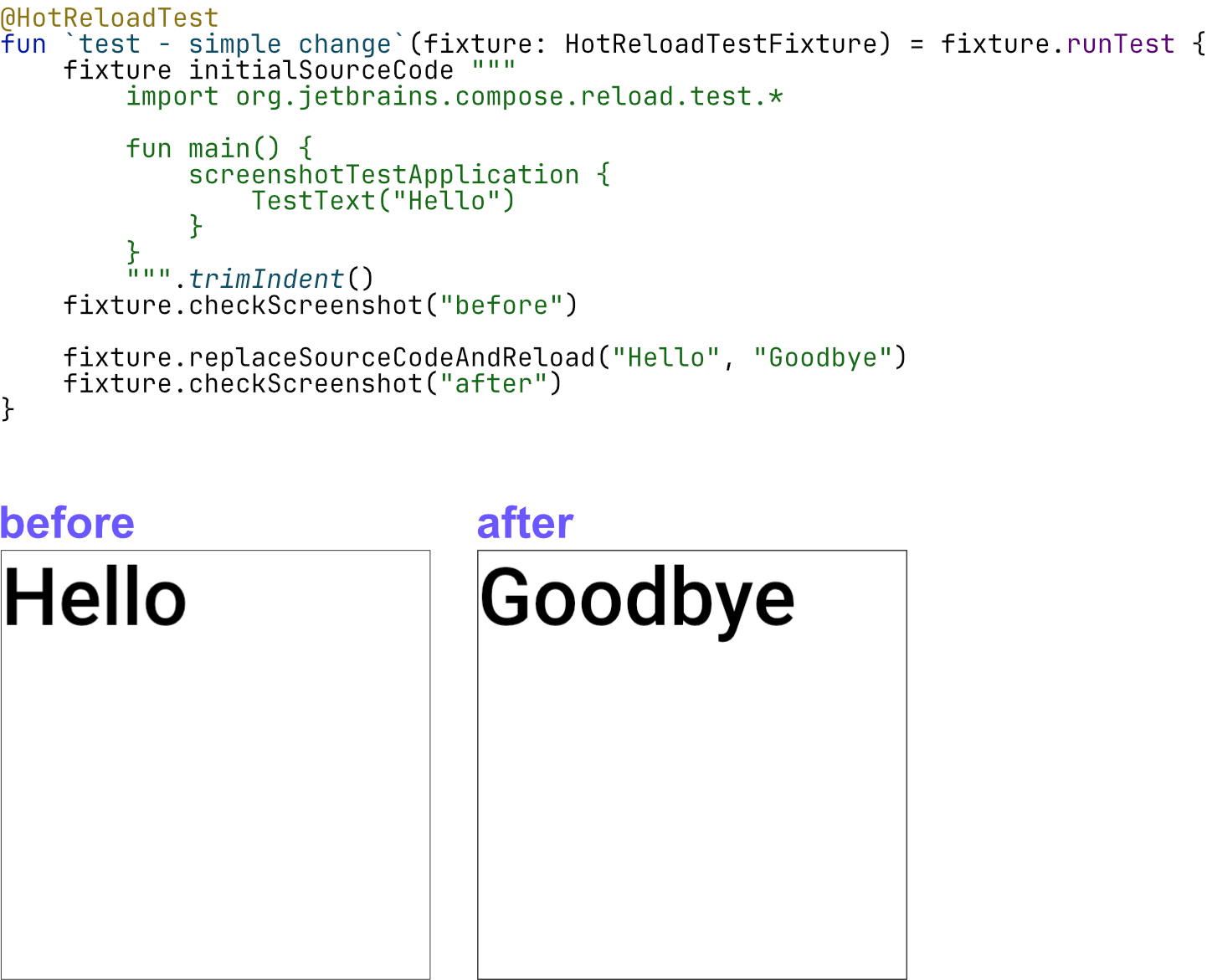

Tests running assertions within the JVM that reload code are called hot-reload unit tests. An example of such a test case was shown earlier in this blog post.

The tests here can define code of interest right next to the actual test function. But the real magic happens when calling the compileAndReload method.

This method allows us to compile the provided source code within the current process and reload it. Once this compileAndReload method finishes, we can safely assume the new code is available and begin to write assertions. The example above shows a test that defines an enum with three cases. After reloading the enum with one case added, we can safely assert that the .entries property contains the newly added case. This test suite implements a custom test executor for Gradle, which launches each test case in a fresh JetBrains Runtime with hot reload enabled and provides a Kotlin compiler for the compileAndReload function. We used such tests in cases where reloading either crashed or had some issues, as mentioned previously (reinitializing statics).

HotReloadTestFixture: Orchestration-based tests

Since this project integrates into many other systems, having a heavier, end-to-end test fixture at our disposal seems natural. Similar to how Gradle plugins would write Gradle integration tests using Gradle-specific fixtures, we have implemented a HotReloadTestFixture that launches actual applications with Gradle in hot-reload mode and communicates with Gradle and the application using the previously mentioned orchestration protocol. Such tests were implemented to cover the integration with the JDWP commands for reloading and testing generic Gradle tasks, but they were also very useful for building screenshot tests:

Just as unit tests do, orchestration-based tests have a convenient way to replace code, thanks to the HotReloadTestFixture; however, this test fixture actually changes source code on disk and thus relies on the entire Gradle/Compose Hot Reload machinery to pick the change up correctly, issue the reload request, and perform other relevant actions, right up until Compose actually updates the UI. After that, the test then takes a screenshot. We have many tests that ensure, through screenshots, that the code change was handled properly, i.e. that only the corresponding state was reset and the UI picked up the changes.

Testing the backwards and forwards compatibility of the orchestration protocol

As we mentioned before, compatibility is one of the key properties of the orchestration protocol. For example, the IDE might have a different client version bundled compared to the server version hosted by the application.

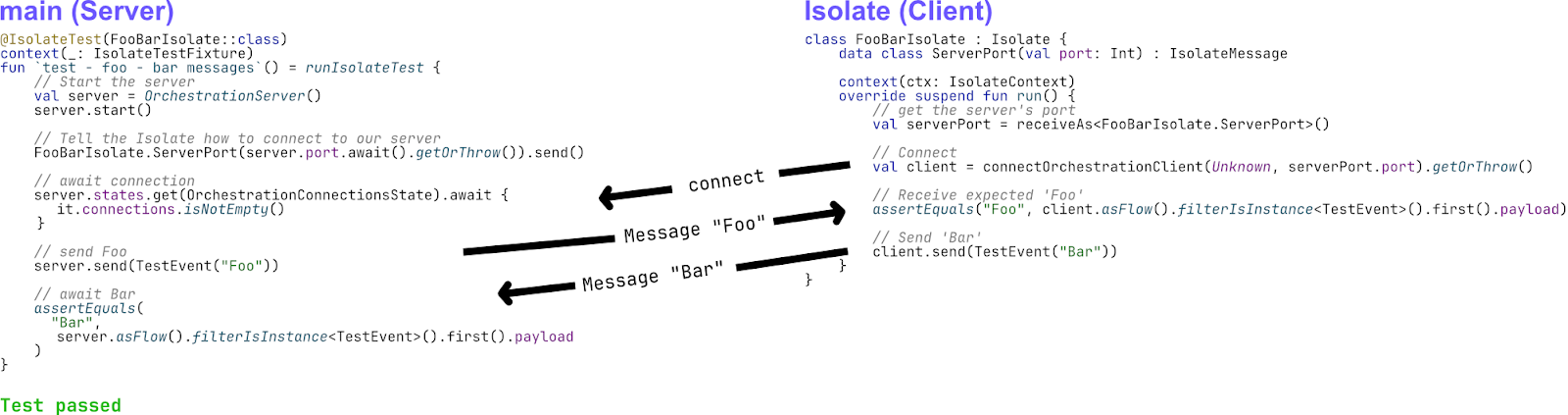

Such compatibility tests typically define a communication flow between a server and a client. Let’s say the client connects, the server sends a message Foo, and the client responds with Bar. Now, to test the compatibility, this flow will be separated into two parts:

The first part is called main, which contains one side of the communication (e.g. the server’s) and runs with the currently compiled version of the code. The second part is called Isolate, and this code will be running in a separate process, launched with the previous JARs of the protocol.

The Isolate class can be defined right next to the test function, making it easy to write compatibility test cases where both ends of the communication are close together. Still, only one will be launched in isolation, running the test against many different, previously released versions of Compose Hot Reload.

Continuing the journey

Compose Hot Reload is a very complex technical project, and we are proud of the engineering work behind it. We tried to highlight what we consider the most interesting aspects of Compose Hot Reload in this blog post. But if you are interested in learning more about the project, check out our GitHub repository. And don’t hesitate to create new issues or discussions if you have any questions or ideas.

Compose Hot Reload version 1.0.0 is bundled automatically with the latest Compose Multiplatform 1.10 release. But we are continuing to work on improving both the IDE experience and the underlying technology. So check out our latest releases and share your feedback!

Subscribe to Kotlin Blog updates