Kotlin

A concise multiplatform language developed by JetBrains

Improving Java Interop: Top-Level Functions and Properties

Kotlin has had top-level functions and properties from day one. They are very convenient in many cases: from basic utilities to extensions for standard APIs.

But Kotlin code is not the only client, and today I’m going to explain how we are planning to improve on the Java interop when it comes to calling top-level functions and properties.

Basics

Top-level functions are compiled to static methods in the byte code, so that

package foo.bar

fun demo() { ... }

becomes

package foo.bar;

public class BarPackage {

public static void demo() { ... }

}

Or at least you can think of it this way. :)

Properties are very similar, only they are translated to a field and accessor(s):

package foo.bar val prop: String = ...

becomes

package foo.bar;

public class BarPackage {

static String prop = ...;

public static String getProp() { return prop; }

}

Note the name of the class: BarPackage. It is derived from the short name of the package: bar. The rest is easy: static methods. So, we can refer to them from Java:

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println(BarPackage.getProp());

}

Package-parts and facades

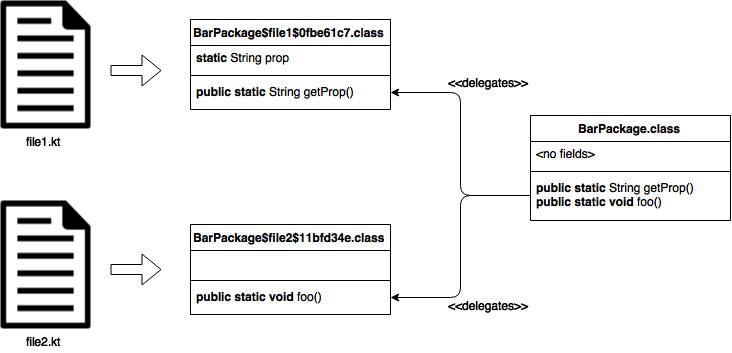

In fact, it’s all a little trickier: top-level functions and properties become statics in Java classes, and we can access them through a class named after the package, yes, but that class is only a facade. The actual layout of the code is as follows:

Every source file is compiled into a separate class file. Even when they are in the same package. Those per-source-file classes are called package-parts. They contain all the actual byte code of methods and declare all the fields. So, all implementation resides in package-parts.

Then, a single package-facade class is generated that declares all the top-level functions and properties (again), and delegates implementations to the package-parts.

Why

Why have a single facade. This is something we are going to change, but here’s the reasoning we followed a few years ago when we made this decision: having a single entry point class for Java clients seems to be as simple as it gets. Also, moving functions from one file to another doesn’t break anything since we refer to them only through the facade, don’t we? Win-win, isn’t it? Well, not quite in fact, but we’ll get to it later, and for now will just explain the rest of the design taking the need for a facade for granted.

Why package-parts. The main reason is initialization order for static fields. Indeed, consider these two files:

file1.kt:

package foo.bar val a = computeA()

file2.kt:

package foo.bar val b = computeB()

When we access a or b from Java, in what order should their initializers be called? In fact, it may be a very complicated question, because computeA() and computeB() may depend on one another (directly or indirectly, through other code). And they may have side-effects, so this actually matters.

So, Kotlin’s answer is:

- inside a single file properties are initialized top-down,

- upon the first access to any code in this file.

Loops may happen (and lead to errors), but this is inevitable and Java has it the same way with statics, doesn’t it? So the implementation piggybacks on the Java’s semantics for static class initializers: every file has its own package-part, which declares all the fields and initializes them in the <clinit> method (that corresponds to the static {...} initializer in the Java language). Thus fields are initialized upon first access. And we get thread-safety for free, which is a big plus. If not for package parts, we couldn’t make it work.

Package-part names

As you might have noticed in the picture above, package-parts tend to have weird names, such as BarPackage$file1$0fbe61c7.class. This consists, obviously, of a package-facade name (BarPackage), a short name of the source file (file1) and a hash-code of the absolute path to the source file. Yes, an ABSOLUTE path. There’s no other way to be sure that two package-part names won’t clash.

If you ever saw an exception stack trace from a Kotlin program, you probably noticed those hashes, they are just ugly. The bigger problem is that they may change when the project is built on another machine (which is not unlikely to have the source tree located in another directory). This may cause trouble, and it did, a few times.

Package-facade names, again

Now it’s time to talk about REAL trouble that keeps biting us and our users more or less all the time. Let’s face it: package-facade names do clash.

How it usually happens: you have two modules, a and b, and in a you have a top-level function declared inside the foo.bar package. Everything is fine until you add another top-level function into the same foo.bar package in another module, b. As soon as you do that, both modules generate class files with the same fully-qualified name: foo.bar.BarPackage, and there’s no chance for the runtime to distinguish them. And you get a NoSuchMethodError, because only one of the two facades is loaded at run-time, and the function from the other one is not there.

(Compilation may break too, but it is not that bad.)

The new design

Well, it took me a while to explain how things work at the moment. But this was only to tell you that we are going to change it :)

So, the design described above has some problems:

- package-facade clashes are painful and very likely in projects of considerable sizes,

- package-part names are ugly because of hashes,

- Java APIs are not that pretty with

BarPackageall over them: those names are not very informative.

To mitigate these problems, we decided to:

- get rid of the single-facade paradigm,

- name package-parts after file names (

Foo.kt->Foo.class), - provide a file-level annotation to customize Java class names,

- allow multiple files to have the same custom name for the cases where facades are actually relevant.

Consequently:

- you can not have files with the same name if they declare members of the same package (e.g. both have

package foo.barat the top), - you can refer to top-level functions from Java by the file name (

File1.foo()), - renaming a file requires the clients to be recompiled, unless you have customized the class name with the annotation.

Example 1. By default, each file is compiled to a class named after it:

file1.kt:

package foo.bar

fun foo() {...}

becomes

package foo.bar;

public class File1 {

public static void foo() {...}

}

Example 2. We can change the name of the class by providing a file-level annotation:

@file:jvmName("Utils")

package foo.bar

fun foo() {...}

becomes

package foo.bar;

public class Utils {

public static void foo() {...}

}

regardless of the source file name.

Example 3. We can hide many package-parts generated for individual files behind a facade by specifying the same JVM name for many files:

file1.kt:

@file:jvmName("Utils")

package foo.bar

fun foo() {...}

file2.kt:

@file:jvmName("Utils")

package foo.bar

fun bar() {...}

generates File1.class and File2.class containing implementations and a facade:

package foo.bar;

public class Utils {

public static void foo() { File1.foo(); }

public static void bar() { File2.bar(); }

}

A small bit on metadata

When we had a single package-facade, we could look into it and find all members of the package at once. Now there’s no single place to look into, and this may affect the compilation performance, so, for each module, the compiler will generate a special file META-INF/<module name>.kotlin_module and store a mapping from packages to package-parts there. This will facilitate rapid discovery of top-level members.

Conclusion

The new scheme liberates us from the issues of the old one. Class name clashes are still possible, but no more probable than they are for normal classes.

This blog post describes the design we are going to implement soon.

If you have feedback, it is very welcome!

Subscribe to Kotlin Blog updates