JetBrains Research

Research is crucial for progress and innovation, which is why at JetBrains we are passionate about both scientific and market research

How Students Are Using AI-Powered Hints in Programming Courses

Learning to code in an online course can feel like hitting a wall again and again, without much help moving forward. Our research team wanted to change that. That’s why our Education Research team built an AI-powered hints tool that doesn’t just point out errors but helps students understand them. As described in our blog post last summer, students can use the tool in JetBrains Academy courses to get tailored guidance nudging them towards the solution instead of staring blankly at a stubborn piece of code or waiting for help on a forum.

Since then, our researchers have investigated how students actually use the tool and published the results in a paper that they will present at the Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE TS) February 19 in St. Louis, Missouri. In this blog post, we will explain how the study was set up, its results, and our analysis.

Learning to code with the help of smart feedback

In the last post, we covered the history of online learning and the importance of feedback in any type of learning environment. Online programming courses can differ a lot in format, especially in how they encourage students to practice writing and running code within the course.

Many online learning platforms, such as Udemy, Codecademy, and edX, provide online editors for students to complete the exercises. Learning programming inside a code editor is easier than installing and learning new software, but in the long run it means that the student is unfamiliar with the relevant professional environment. Other platforms, such as Hyperskill, offer a hybrid option, where the student can also learn in a professional integrated developer environment (IDE) if they choose to do so. The downside of a hybrid course is that some students might not choose to use the IDE, for example if they consider it a hurdle to install and learn to navigate new software.

For our JetBrains Academy courses, we released the JetBrains Academy plugin a few years ago, which lets educators build complete courses directly inside the IDE. With this setup, students can read theory and immediately apply it by solving practical tasks in the very same environment they use to write code. As a result, they can become comfortable working in IDEs early on and are better prepared for real-world software development roles.

A recent addition to our plugin is the AI-powered hints tool, developed by our Education Research team. The tool leverages powerful IDE features by combining static analysis and code quality checks with LLMs to provide personalized hints to students. In the previous paper, we conducted evaluation studies to gauge how useful students found the tool while learning, as described in the previous blog post.

To help students even further, we wanted to know more about how they are really interacting with the tool and discover possible new behavior patterns. In the rest of this blog post, we will talk about exactly this: how students are actually interacting with the AI-powered hints tool.

Smart feedback in online learning

Recent years have seen many studies exploring how students interact with intelligent tutoring systems, offering useful directions for future system design. In this short subsection, we will provide a summary of recent studies, plus describe what our study adds to the field.

Researchers in this study examined an intelligent next-step hint system to understand why students ask for help, looking at factors such as time elapsed and code completeness after each hint, and identifying reasons like difficulty starting an exercise. This work provides general insights into students’ hint-seeking patterns, but without the details (e.g. keystroke data). This study analyzed when and how to provide feedback and hints using keystroke datasets annotated with points where experts would intervene, but did not look at students’ actual interactions with hint systems.

In this paper, researchers investigated how different hint levels support task completion and why students request hints, using a think‑aloud study with pre‑ and post‑tests for 12 students. However, we would have liked to see broader usage patterns or how learners cope with unhelpful hints.

More recently, researchers studied how students use on-demand automated hints in an SQL course and how these hints affect learning, using A/B testing to identify behavioral differences and simple patterns. For example, they found that students often request a second hint within 10 seconds of the first one. While this research sheds light on basic behavioral trends, it mainly asks whether adding a hint system supports learning, rather than closely examining the interaction patterns themselves.

Overall, prior work has focused on why and when hints are given, but far less on how students actually work with them in practice. In our study, we applied process mining techniques to uncover detailed behavioral patterns in how students interact with hints while they solve programming tasks. In addition, we conducted interviews with a subset of the students to learn more about how they interact with the hints tool in specific scenarios.

Our investigation into students’ behavioral patterns

With our study, we wanted to better understand how the students are really interacting with the tool, as well as how students navigate situations with less helpful hints. Specifically, our two research questions were:

- What behavioral patterns can be identified based on students’ interaction with the next-step hint system?

- What strategies do students use to overcome unhelpful hints?

Our study collected data in two steps. First, we collected information about all of the students’ interactions with the hints system, analyzing these interactions quantitatively. Then, we selected a subset of six students to interview for about 30 minutes, so that we had a qualitative and in-depth complement to the quantitative analysis. In the next subsection, we will tell you about the methodology for each step. The subsection after that will present the results and analysis.

Quantitative behavioral analysis

For the first part of the study, we analyzed detailed problem-solving data from first- and second-year Bachelor’s students working on programming tasks in our introductory Kotlin course. The selected projects represent different levels of complexity and cover basic topics such as variables, loops, conditional operators, and functions. The 34 participants had previously completed at least one programming course in another language, and they had no experience with Kotlin before. We asked these students to complete three projects from the course, using the hint system whenever they wanted.

We used KOALA to capture keystrokes, IDE actions, the windows they accessed, and rich information about their hint usage. Hint-usage information included details like when hints were requested and for which specific tasks. The resulting dataset contains:

- 6,658,936 lines of code

- 1,364,943 IDE activity events

- 960 textual hint requests

- 453 code hint requests

Note: This dataset is open source, and we encourage you to take a look. It can be used for further analysis in a research project, or even just for educators to see how beginner learners are programming.

Process mining and our dataset: Preliminaries

After collecting this data, we conducted a quantitative analysis of the students’ behavior. To do this, we used a process mining technique. Process mining turns log or event data into behavioral models using action analysis, taking into account both event frequency and sequence. In business settings, the technique can help companies see where improvements are needed, as is argued for in this process mining manifesto, and save a lot of money, for example, by finding instances of duplicate payments or minimizing complex order delays.

Although it is primarily used in industry settings, process mining has already been applied in educational domains (see this paper and this paper for examples). As far as we know, we are the first to use process mining to analyze programming hint systems.

To apply this technique to our hint-systems dataset, we first extracted all hint-request sessions from the dataset (1,050 in total). The data from these sessions are the input for the analysis, which uses specialized algorithms to map the activities and transitions between them.

The sessions began when a student requested a hint. By clicking Get Hint or Retry, they ended when it was clear that the hint was processed, either by accepting the code hint or closing the text hint banner. The session was also considered “over” if the student ran into an error or there was no activity for five minutes.

We also defined different activities within sessions. Here are the activities:

- Hint Button Clicked: The student clicks Get Hint to generate a hint.

- Hint Retry Clicked: The student clicks Retry to regenerate a hint.

- Hint Code Generated: The code hint is generated. By tool design, this action is triggered every time Get Hint is clicked.

- Hint Banner Shown: The banner with a textual hint is shown to the student. Although this action is carried out by the system, not by the student, it marks the moment when the student has viewed the hint. This action will be used for a more detailed analysis.

- Show Code Hint Clicked: The student clicks Show Code to show a code hint.

- Hint Accepted: The student clicks Accept to accept a code hint.

- Hint Banner Closed: The student closes the textual hint banner.

- Hint Canceled: The student clicks Cancel to decline a code hint.

- Error Occurred: This action includes cases where internal errors occurred during the hint generation process, e.g. problems with the internet connection, or when the LLM did not provide a response.

All sessions began with items 1 or 2, i.e. clicking Get Hint or Retry. A session could end with different activities, with the most common being items 6, 8, and 9: Hint Accepted, Hint Canceled, or Error Occurred.

In the analysis, we coded the sequence of activities within each session. We also grouped the sessions into the following three main types:

- Positive Student accepted the code hint

- Neutral Student saw a hint but didn’t clearly accept or reject it

- Negative Student canceled a hint or got an error

The first and last types are straightforward: For the positive type, the session ended when the student accepted the code hint. For the negative, the session ended because the student did not use the hint, having received an error or actively cancelled the hint.

The neutral type will be looked at in more detail in the next section, as it required additional analysis to determine how helpful the student found the hint. We know by the actions carried out that the student saw a text or code hint, but they proceeded without explicitly accepting the code hint. Examples of neutral sessions include the following (Hint Code Generated has been omitted, as it automatically occurs as the second step in each):

- Hint Retry Clicked → Hint Banner Shown

- Hint Button Clicked → Hint Banner Shown → Show Code Hint Clicked

- Hint Retry Clicked → Hint Banner Shown → Hint Banner Closed

The numbers below shows the distribution of session types among the 1,050 total sessions.

- Positive: 299 (28%)

- Neutral: 420 (40%)

- Negative: 284 (27%)

The above shows that strictly positive sessions make up about a third of all sessions. As will be discussed below, we found out that the neutral cases often actually were successful in helping the students with their tasks, even if not positive as defined above. Namely, in these cases students clearly analyzed and used the content of the hints but did not automatically apply them.

Note that 266 of the 284 (94%) negative sessions ended with errors, rather than the student cancelling the hint. These errors were either internet connection issues on the student side or a system issue on our side; we have already fixed any such system errors. In addition to these three types listed above, we collected 47 data points, accounting for 4,5% of the sessions, that were not classifiable based on the available data.

With these preliminary data about the “events”, we were able to move on to applying the process mining technique for our analysis. The next subsection describes these results.

Process mining and our dataset: Analysis

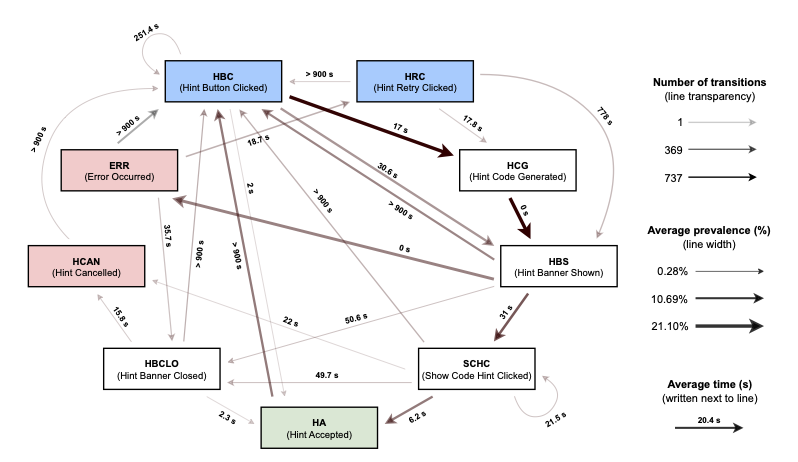

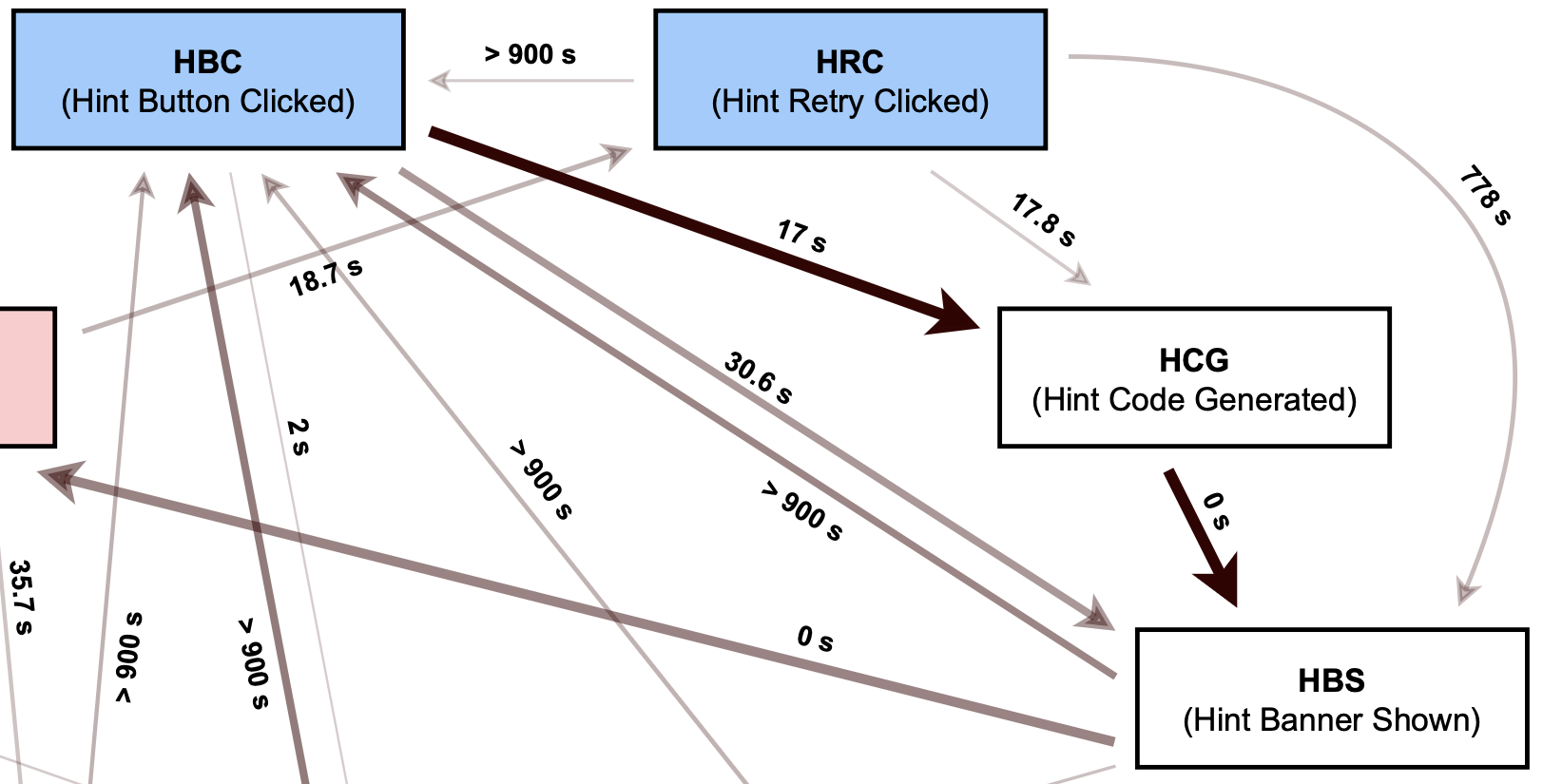

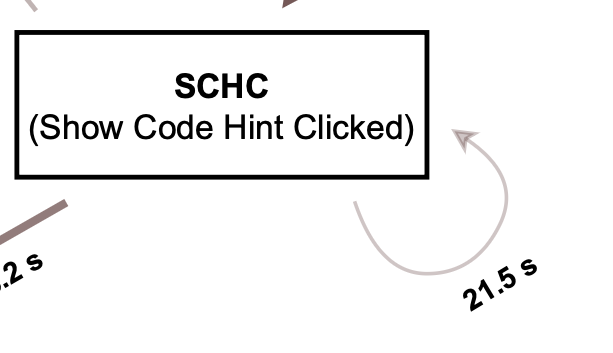

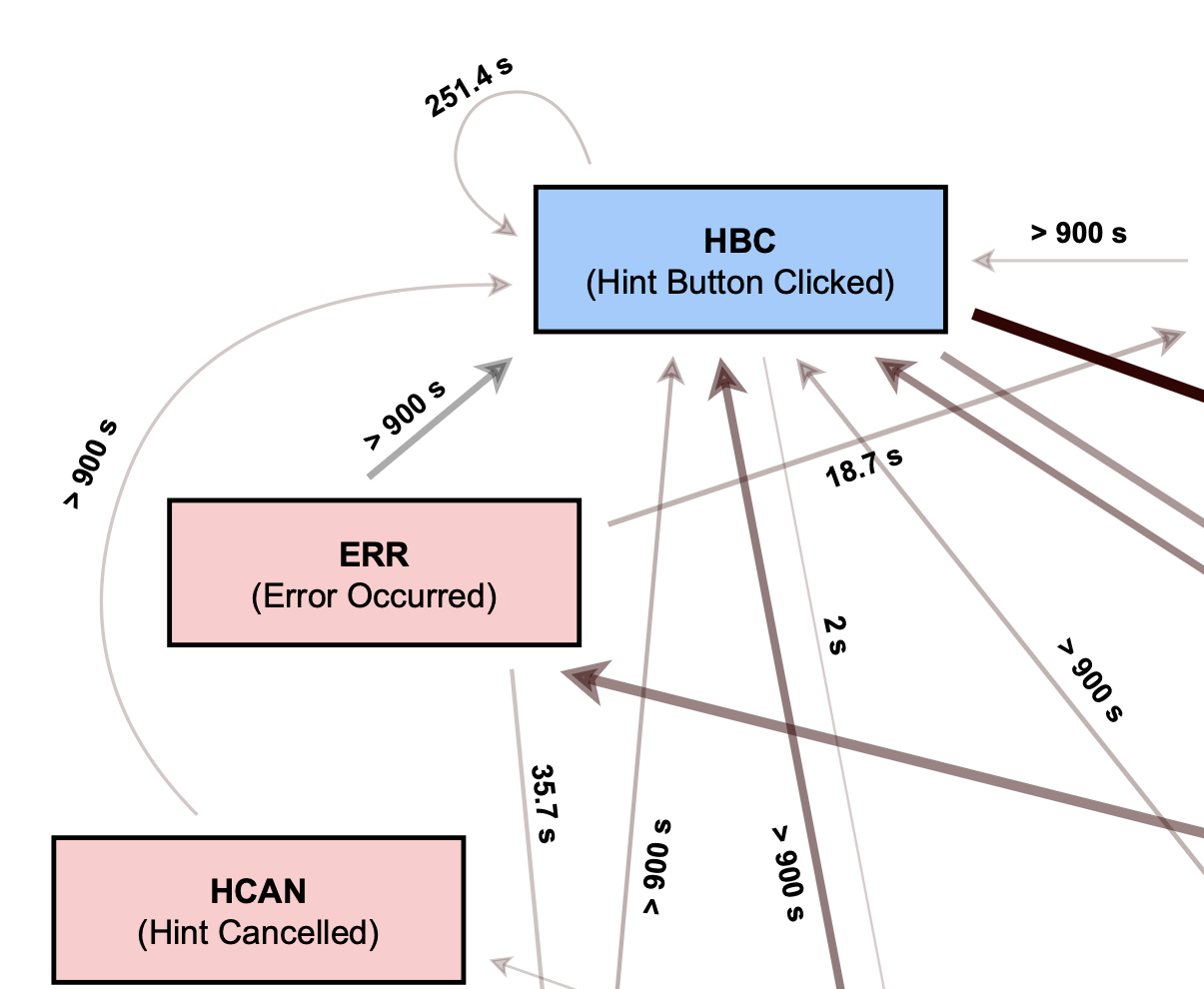

We turned the data described in the previous subsection into a map of how students moved through the system. This sort of map is also called a process behavior graph. The graph for our dataset is displayed below; as it is quite complex, we will explain the most important parts individually.

In the above graph, some boxes are colored, while others are not. The blue boxes at the top represent activities that begin a session, either by generating a new hint or retrying a hint; the red boxes on the left represent activities that end a negative session; the green box at the bottom is the activity that can end a positive session; and the other activities represent activities that can otherwise happen during a session.

The arrows indicate the direction of transitions, and the numbers next to the arrows indicate the average time in seconds for each transition. Longer times, particularly those around 900 seconds, indicate that the student was solving the task and then returned for another hint. In those cases, a new event would have been triggered.

Each arrow’s transparency and thickness represent information about the frequency and average prevalence. As can be seen in the fragment below, the most frequent transitions occurred from the blue box Hint Button Clicked to white boxes Hint Code Generated and then to Hint Banner Shown.

The arrows that circle back to themselves, such as in the snippet below, represent those instances in which students repeatedly clicked the same button. In the case of the white box Show Code Hint Clicked, we think this suggests that the student might not have understood how the code hint worked, and that a future iteration of the tool would need to provide more explanation to help the student.

Looking more closely at the negative sessions, we can see in the following image two arrows coming from the red box labelled ERR. The right arrow with an 18.7-second average leads to HRC, or Hint Retry Clicked. The left arrow with > 900 s leads to HBC, or Hint Button Clicked.

These patterns indicate that even when the student encountered an error, such as a bad internet connection, they persisted in generating a new hint, either within the same task or in another. This is an important insight because it shows that students are motivated to use the hints tool even when encountering errors or negative scenarios.

In the image below, we can also see that between the blue Hint Button Clicked and various white boxes, there is an arrow going back to the blue HBC button. We interpret these transitions as indicating that the students modified their code to generate additional variations of the same hint before integrating the information into a solution. That is, the pattern suggests that they did not simply click Accept Hint, but tried to solve the task themselves.

In the classification part of the analysis described in the previous subsection, these types of activities usually comprised the sessions labelled as neutral, as they often did not end with the student accepting the hint. These and other unexpected patterns were why we wanted to hear more from these students about why they behaved the way they did.

Qualitative behavioral analysis

As described in the previous section, we observed three types of sessions when the students interacted with the AI-powered hint system. We categorized a session as positive when the student ended the trajectory by clicking Accept Hint, as the tool is working as intended. We categorized a session as negative if the student received an error message or they themselves canceled the hint. Interestingly, the students still persevered in trying for new hints despite errors.

Finally, we categorized sessions as neutral when the student clearly saw the hint but did not end the session like in positive or negative sessions. This means they saw the hint, but did not apply it to their code; for this reason, we do not consider these sessions negative or unsuccessful. Our analysis shows that neutral sessions make up 40% of all sessions, and we were curious about what exactly the students’ strategies were.

In order to learn more about what the students were thinking, we selected a subset of the participants so that they represented different experience levels, as well as locations. We conducted six semi-structured interviews, each lasting approximately 30 minutes. The interviews had two main sections: asking the participants about their experience with AI-powered hints and about any other forms of assistance they might have used while completing the tasks.

Let’s look at what is going on in the neutral scenarios. We will focus on reporting two kinds of behaviors in these neutral scenarios: selective use of hints and combining partial solutions.

Selective use of hints

From these interviews, we learned that some participants chose to work with the code hints manually instead of clicking Accept Hint. The reasons for this depended on the situation: sometimes they chose to manually alter their code for improved learning, i.e. so that they could better remember how to fix the problem next time; sometimes they only wanted to use part of the code hint. We call this behavior selective use of hints.

In the log data, we could see that the students opened the visual diff window in the code editor. This window allows the student to view both their own code and the code hint. After opening this window, the students then manually typed in the recommended code from the hint – if the hint was clear.

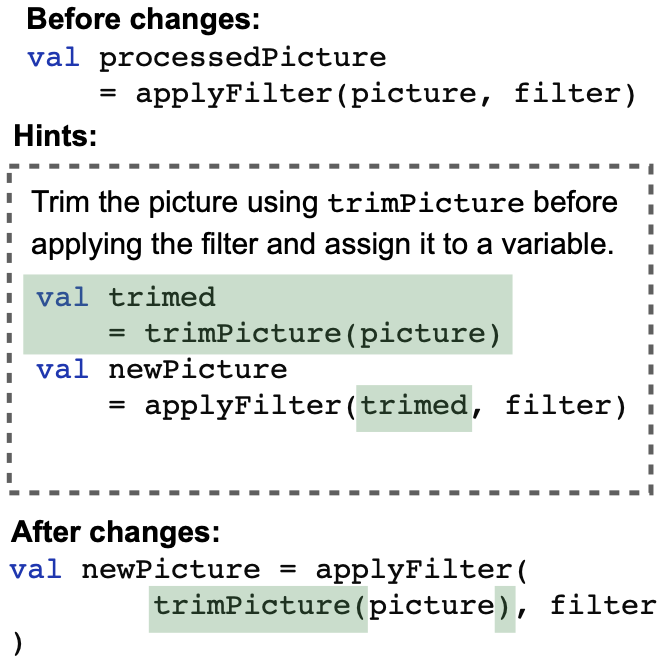

We can show you two examples where the hints were unclear. In the first, the text hint suggested that an image should be trimmed before applying filters, and that this trimming could be done by storing a temporary result in a variable. This can be seen in the image below, inside the box bordered by a dotted line.

As can be seen above, the student did not completely follow the hint; instead they only trimmed the image and did not create a new variable. An advantage of the in-IDE format over a course in an online editor is that the IDE will show the student an optimized way to proceed with the removed variable, even though the hint had suggested otherwise. The student’s strategy in this example suggests that students are not unquestioningly accepting hints, but are actually analyzing and adapting them for their benefit.

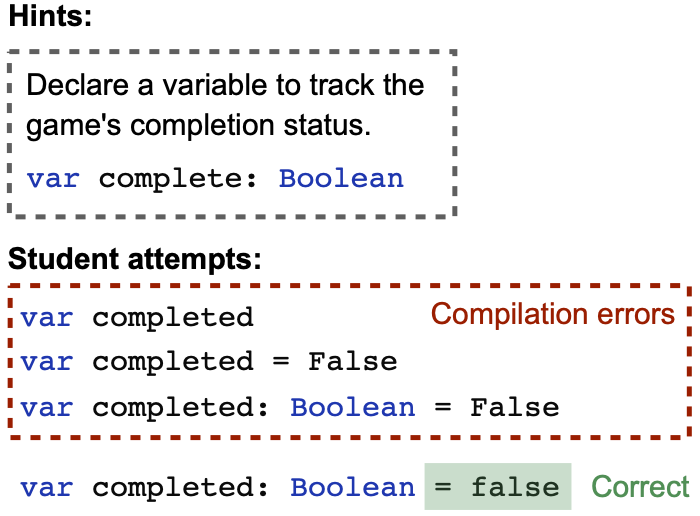

In a second case, the text hint suggested that the student should add a Boolean variable to store the result of a game. The image below displays the hint, as well as the various student attempts, which included a few compilation errors.

The text hint was not wrong, but it did not provide the full story: in Kotlin, Boolean

From looking more closely at the students’ behavior concerning selective use of hints, we learned both that students are actively trying to adapt the hints so that they can learn better and that, in creating the hints, we should take into account language-specific features that a beginner student might not yet know about. Both takeaways form a solid basis for future investigations.

Combining partial solutions

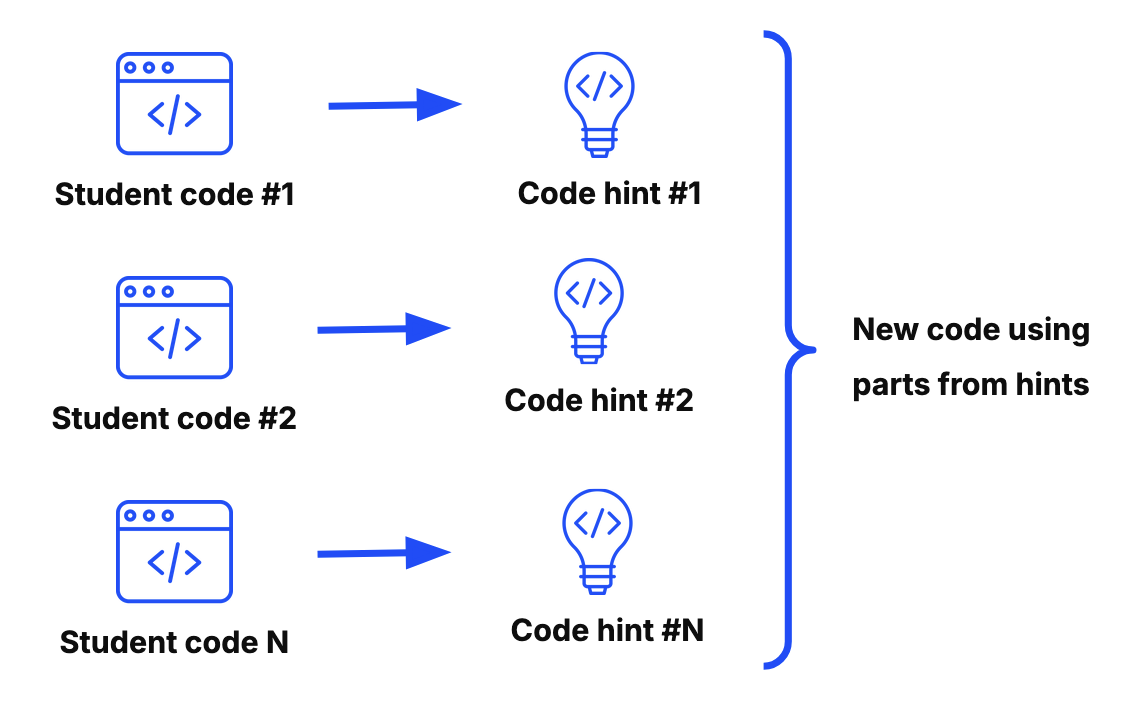

In the qualitative analysis of the AI-powered hints tool, we additionally learned that the students sometimes combined information from multiple hint attempts, instead of using only one hint. In the log data, this appeared as clusters of closely spaced hint requests on the same portion of code, followed by students editing the solution themselves rather than just copy-and-pasting code. This behavior is depicted schematically in the image below.

This behavior, which we call combining partial solutions, can be seen as a strategy to develop a working solution by troubleshooting and making small changes to their solutions, each time generating a new hint. As with the previous behavior, students did not accept the code hint, which is why we categorized it as a neutral and not a positive scenario.

Within this analysis, we found that students often toggled between their original code version and multiple hints: they kept the previous code hint windows open. We did not expect this behavior from students using the hint tool and will investigate further in future work.

We also observed that students sometimes copied their original code outside the task environment, reusing it later alongside new attempts. In the end, they were able to obtain a working solution with this strategy. This is another behavior that we did not expect from the students, and we are interested in investigating it further in the future. More specifically, we would like to provide the participants with multiple hints simultaneously (instead of sequentially), so that they can construct a working solution efficiently and effectively.

From this analysis, we have learned that the hint tool could benefit from better support for partial adoption of hints and designs that embrace the way students naturally mix system suggestions with their own understanding and ideas, so that the student does not have to manually open multiple windows or copy-and-paste code from outside the IDE.

Furthermore, what we can understand from this behavior of combining partial solutions is that the students are active problem solvers. That is, they are not just clicking through the hints so that they can advance to the next step or lesson. Instead, students analyze the hints and adapt them to get even a better solution – critical thinking skills like these are invaluable in the LLM era.

Explore it yourself

Interested in learning programming with the help of our AI-powered hints tool? Check out our JetBrains Academy course catalog.

You can also use our data to do your own research to discover something new about how students use smart feedback in online programming courses.

And finally, if you’re interested in collaborating with our team, let us know!

Subscribe to JetBrains Research blog updates