The “10x” Commandments of Highly Effective Go

This is a guest post from John Arundel of Bitfield Consulting, a Go trainer and writer who runs a free newsletter for Go learners. His most recent book is The Deeper Love of Go.

Ever wondered if there’s a software engineer, somewhere, who actually knows what they’re doing? Well, I finally found the one serene, omnicompetent guru who writes perfect code. I can’t disclose the location of her mountain hermitage, but I can share her ten mantras of Go excellence. Let’s meditate on them together.

1. Write packages, not programs

The standard library is great, but the universal library of free, open-source software is Go’s biggest asset. Return the favour by writing not just programs, but packages that others can use too.

Your main function’s only job should be parsing flags and arguments, and handling errors and cleanup, while your imported “domain” package does the real work.

Flexible packages return data instead of printing, and return errors rather than calling panic or os.Exit. Keep your module structure simple: ideally, one package.

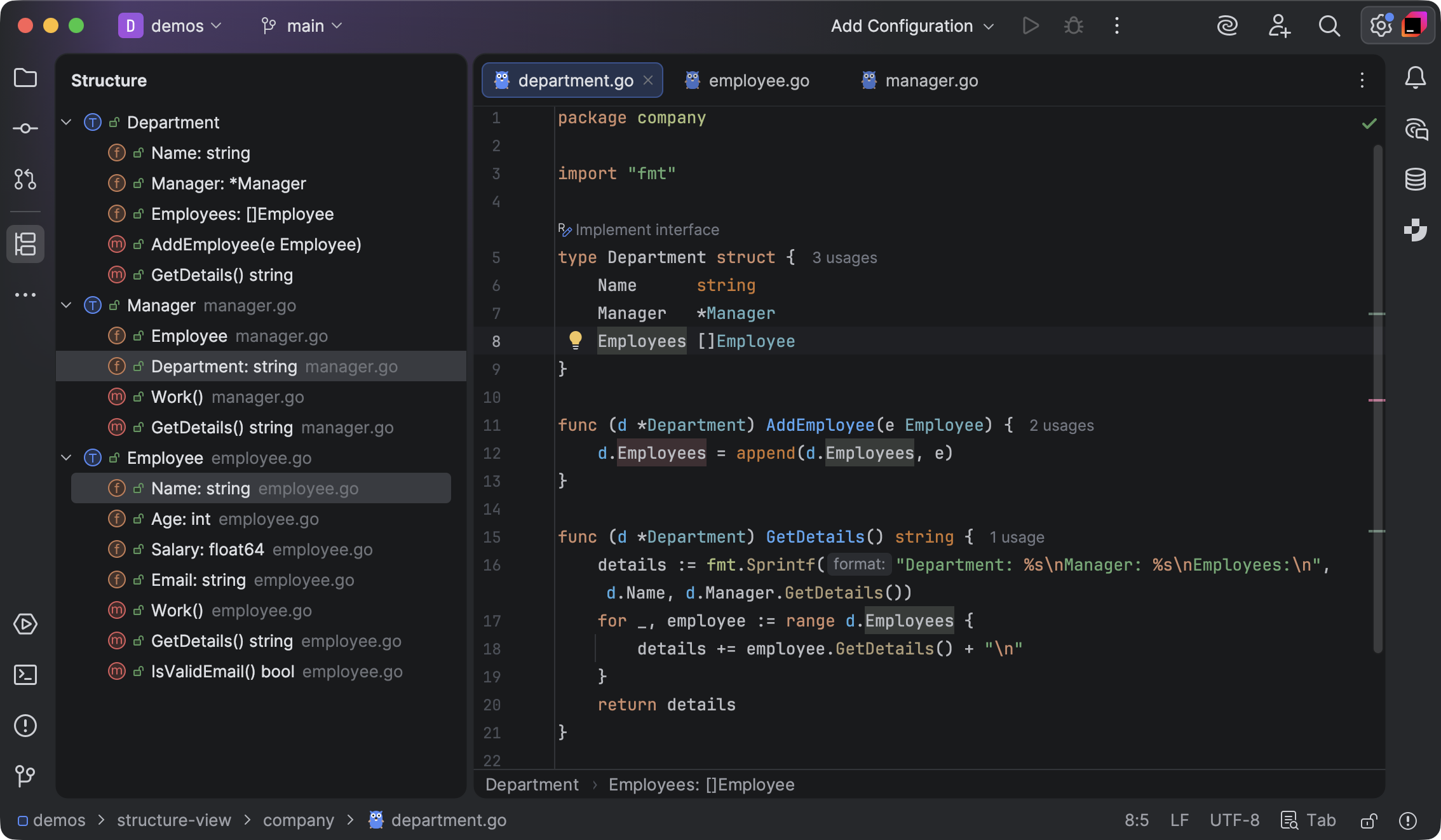

Tip: Use Structure view (Cmd-F12) for a high-level picture of your module.

2. Test everything

Writing tests helps you dogfood your packages: awkward names and inconvenient APIs are obvious when you use them yourself.

Test names should be sentences. Focus tests on small units of user-visible behaviour. Add integration tests for end-to-end checks. Test binaries with testscript.

Tip: Use GoLand’s “generate tests” feature to add tests for existing code. Run with coverage can identify untested code. Use the debugger to analyse test failures.

3. Write code for reading

Ask a co-worker to read your code line by line and tell you what it does. Their stumbles will show you where your speed-bumps are: flatten them out and reduce cognitive load by refactoring. Read other people’s code and notice where you stumble—why?

Use consistent naming to maximise glanceability: err for errors, data for arbitrary []bytes, buf for buffers, file for *os.File pointers, path for pathnames, i for index values, req for requests, resp for responses, ctx for contexts, and so on.

Good names make code read naturally. Design the architecture, name the components, document the details. Simplify wordy functions by moving low-level “paperwork” into smaller functions with informative names (createRequest, parseResponse).

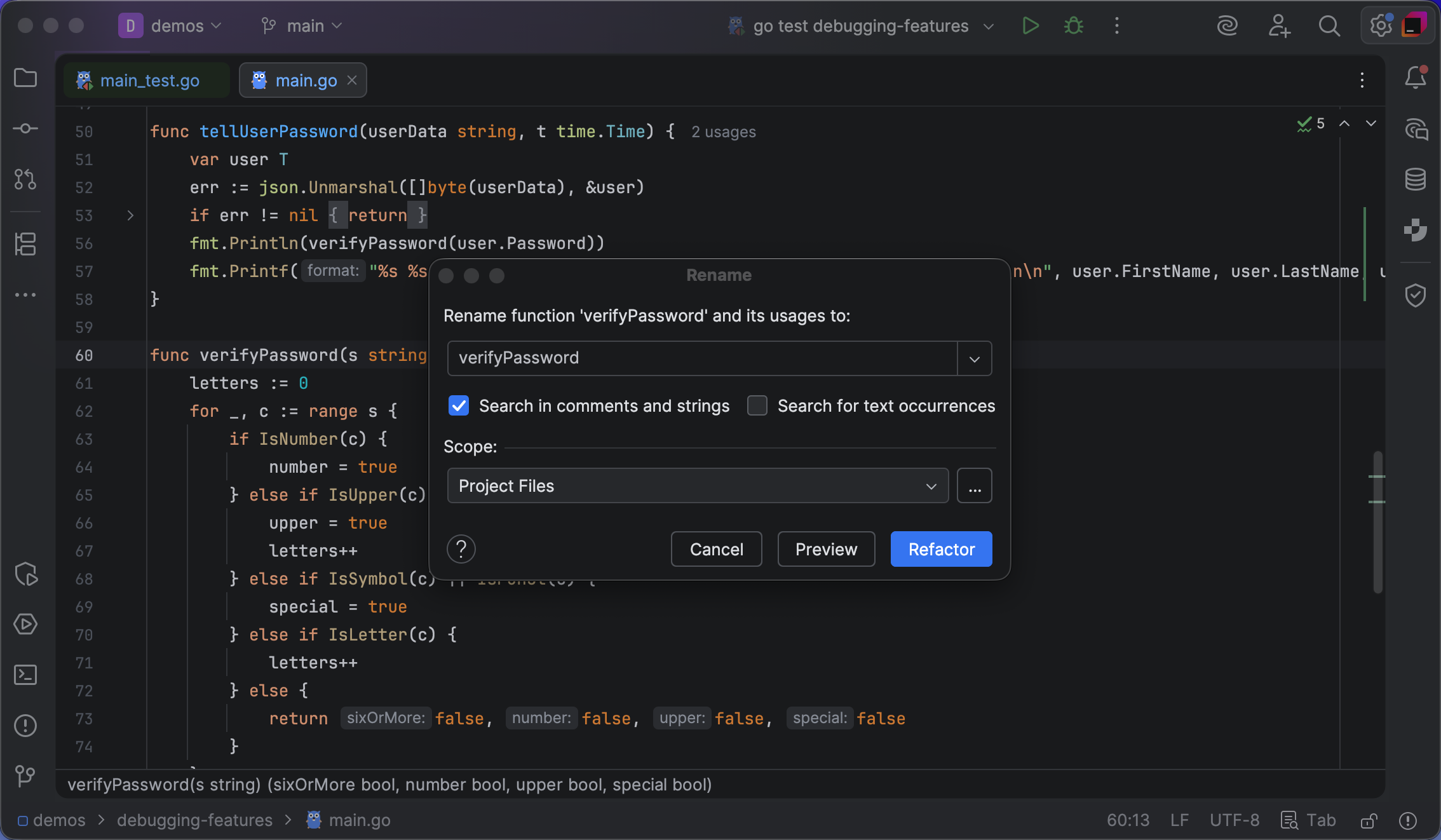

Tip: In GoLand, use the Extract method refactoring to shorten long functions. Use Rename to rename an identifier everywhere.

4. Be safe by default

Use “always valid values” in your programs, and design types so that users can’t accidentally create values that won’t work. Make the zero value useful for literals, or write a validating constructor that guarantees a valid, usable object with default settings. Add configuration using WithX methods:

widget := NewWidget().WithTimeout(time.Second)

Use named constants instead of magic values. http.StatusOK is self-explanatory; 200 isn’t. Define your own constants so IDEs like GoLand can auto-complete them, preventing typos. Use iota to auto-assign arbitrary values:

const (

Planet = iota // 0

Star // 1

Comet // 2

// ...

)

Prevent security holes by using os.Root instead of os.Open, eliminating path traversal attacks:

root, err := os.OpenRoot("/var/www/assets")

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer root.Close()

file, err := root.Open("../../../etc/passwd")

// Error: 'openat ../../../etc/passwd: path escapes from parent'

Don’t require your program to run as root or in setuid mode; let users configure the minimal permissions and capabilities they need.

Tip: Use Goland’s Generate constructor and Generate getter and setter functions to help you create always valid struct types.

5. Wrap errors, don’t flatten

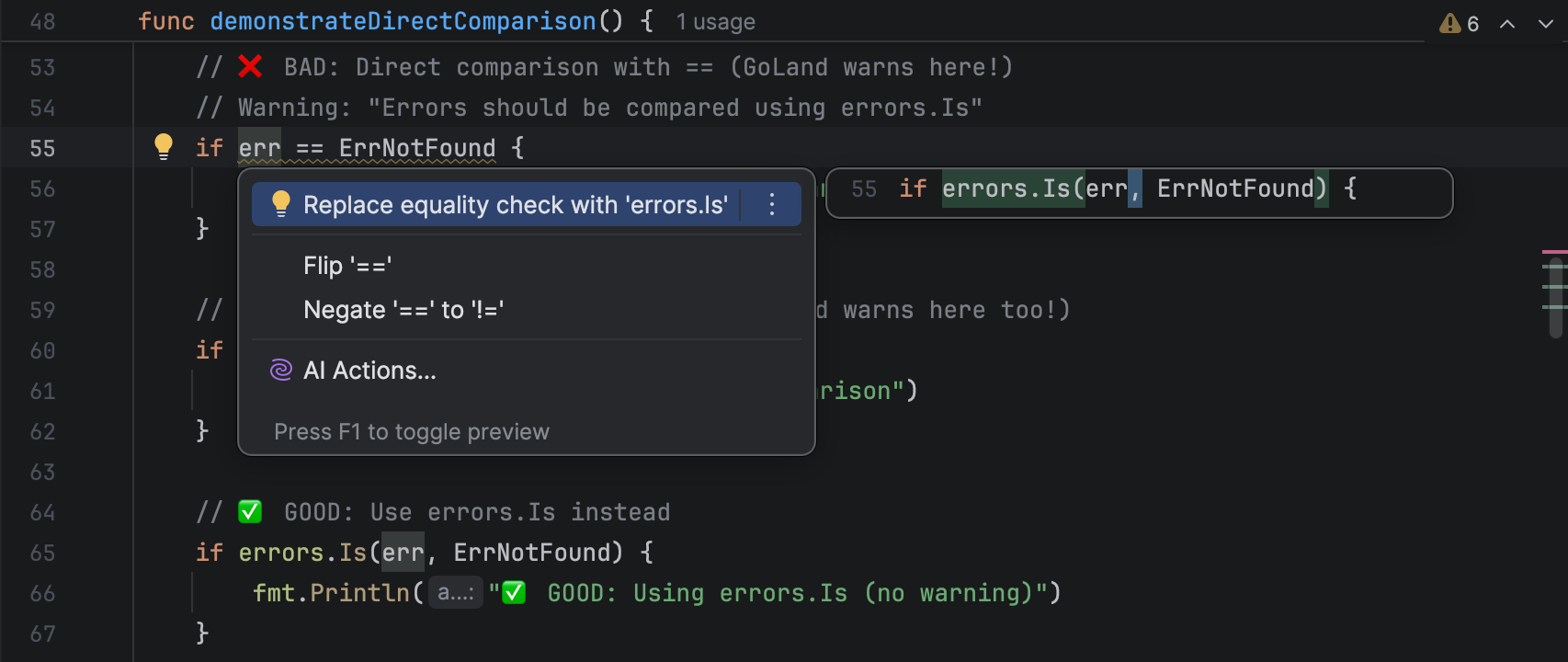

Don’t type-assert errors or compare error values directly with ==, define named “sentinel” values that users can match errors against:

var ErrOutOfCheese = errors.New("++?????++ Out of Cheese Error. Redo From Start.")

Don’t inspect the string values of errors to find out what they are; this is fragile. Instead, use errors.Is:

if errors.Is(err, ErrOutOfCheese) {

To add run-time information or context to an error, don’t flatten it into a string. Use the %w verb with fmt.Errorf to create a wrapped error:

return fmt.Errorf("GNU Terry Pratchett: %w", ErrOutOfCheese)

This way, errors.Is can still match the wrapped error against your sentinel value, even though it contains extra information.

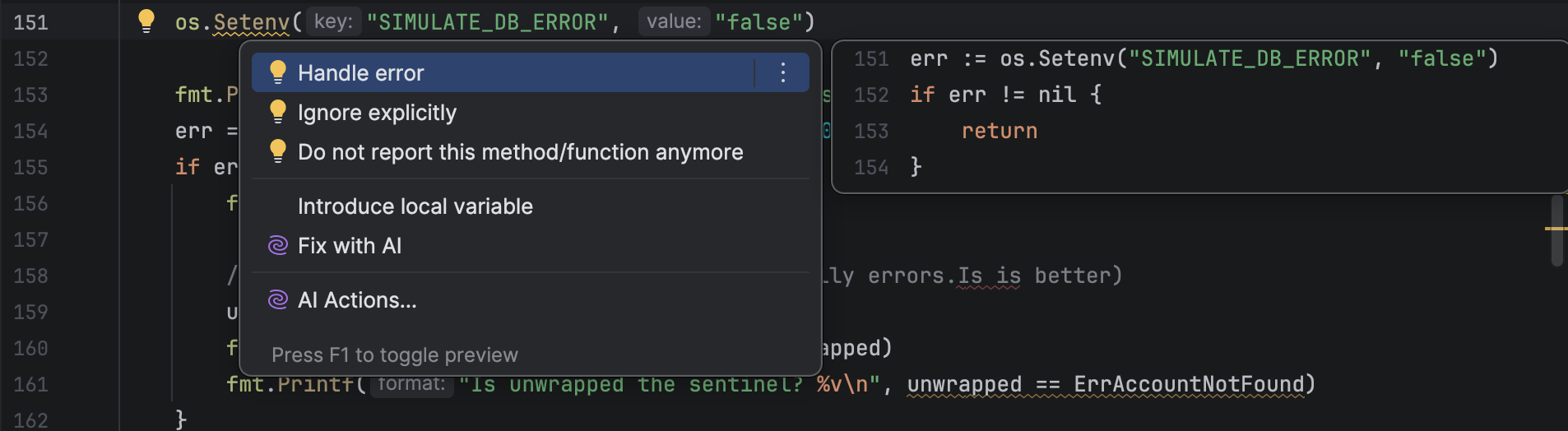

Tip: GoLand will warn you against comparing or type-asserting error values.

6. Avoid mutable global state

Package-level variables can cause data races: reading a variable from one goroutine while writing it from another can crash your program. Instead, use a sync.Mutex to prevent concurrent access, or allow access to the data only in a single “guard” goroutine that takes read or write requests via a channel.

Don’t use global objects like http.DefaultServeMux or DefaultClient; packages you import might invisibly change these objects, maliciously or otherwise. Instead, create a new instance with http.NewServeMux (for example) and configure it how you want.

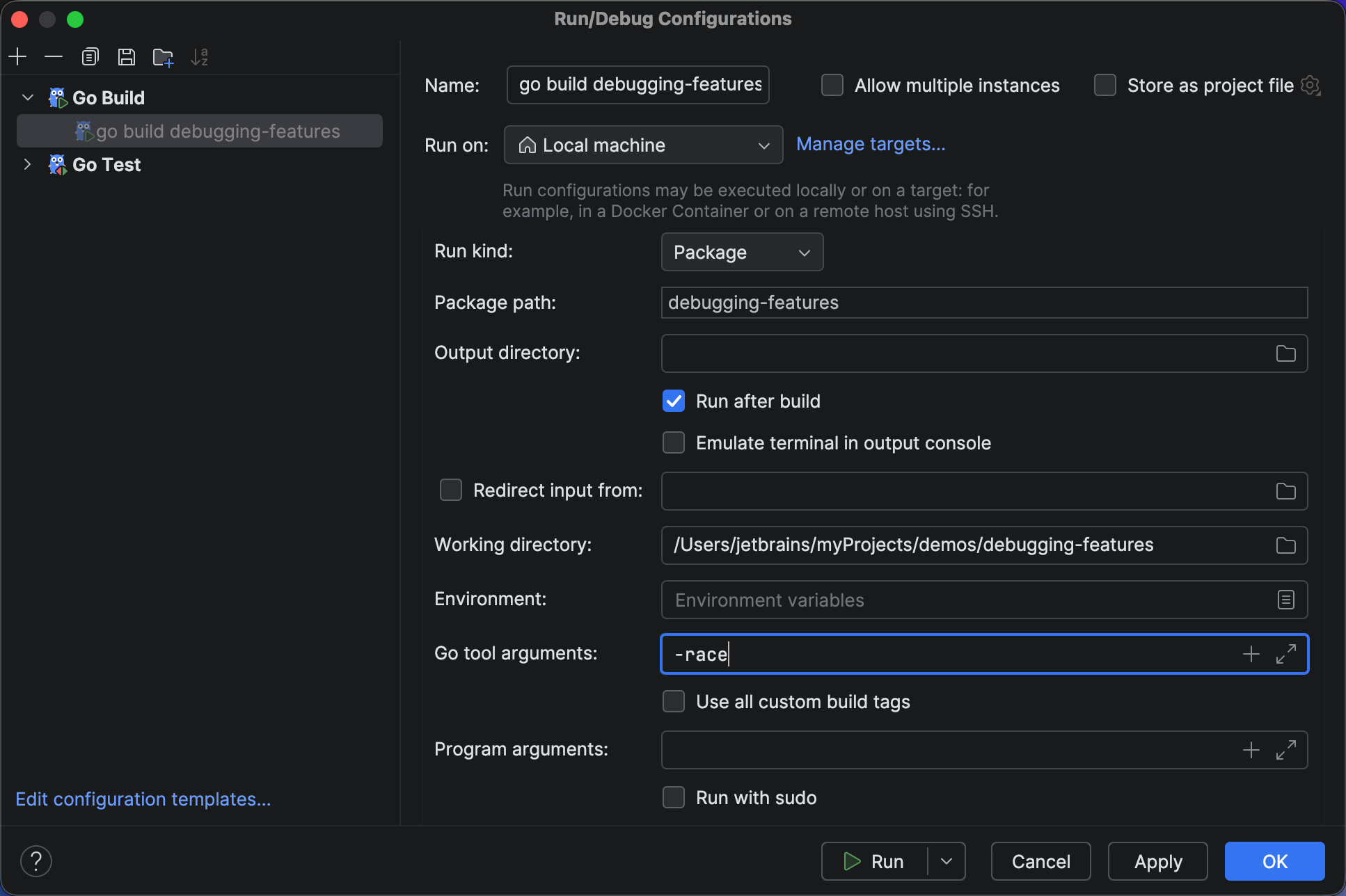

Tip: Use GoLand’s Run/Debug Configurations settings to enable the Go race detector for testing concurrent code.

7. Use (structured) concurrency sparingly

Concurrent programming is a minefield: it’s easy to trigger crashes or race conditions. Don’t introduce concurrency to a program unless it’s unavoidable. When you do use goroutines and channels, keep them strictly confined: once they escape the scope where they’re created, it’s hard to follow the flow of control. “Global” goroutines, like global variables, can lead to hard-to-find bugs.

Make sure any goroutines you create will terminate before the enclosing function exits, using a context or waitgroup:

var wg sync.WaitGroup wg.Go(task1) wg.Go(task2) wg.Wait()

The Wait call ensures that both tasks have completed before we move on, making control flow easy to understand, and preventing resource leaks.

Use errgroups to catch the first error from a number of parallel tasks, and terminate all the others:

var eg errgroup.Group

eg.Go(task1)

eg.Go(task2)

err := eg.Wait()

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("error %v: all other tasks cancelled", err)

} else {

fmt.Println("all tasks completed successfully")

}

When you take a channel as the parameter to a function, take either its send or receive aspect, but not both. This prevents a common kind of deadlock where the function tries to send and receive on the same channel concurrently.

func produce(ch chan<- Event) {

// can send on `ch` but not receive

}

func consume(ch <-chan Event) {

// can receive on `ch` but not send

}

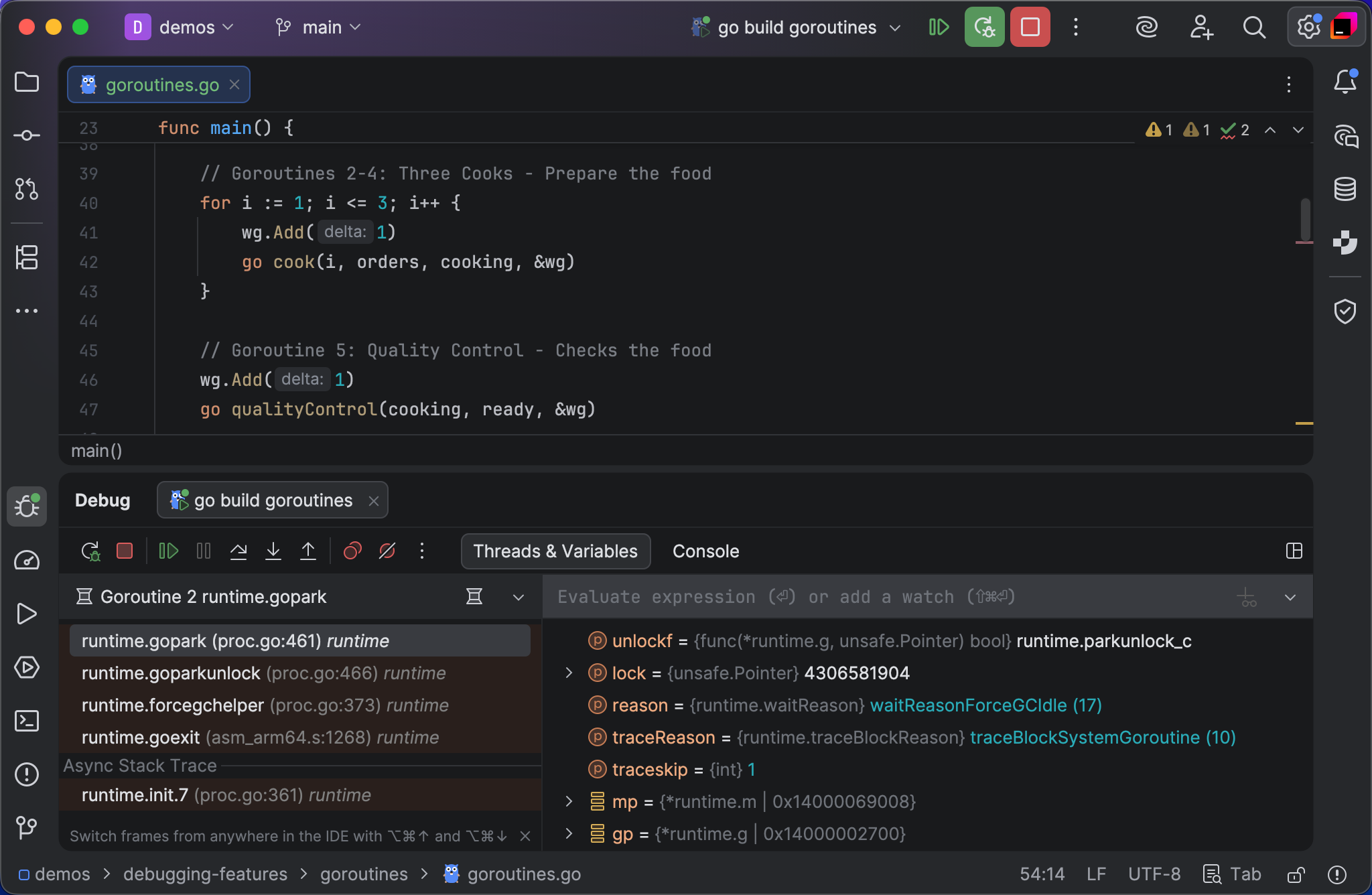

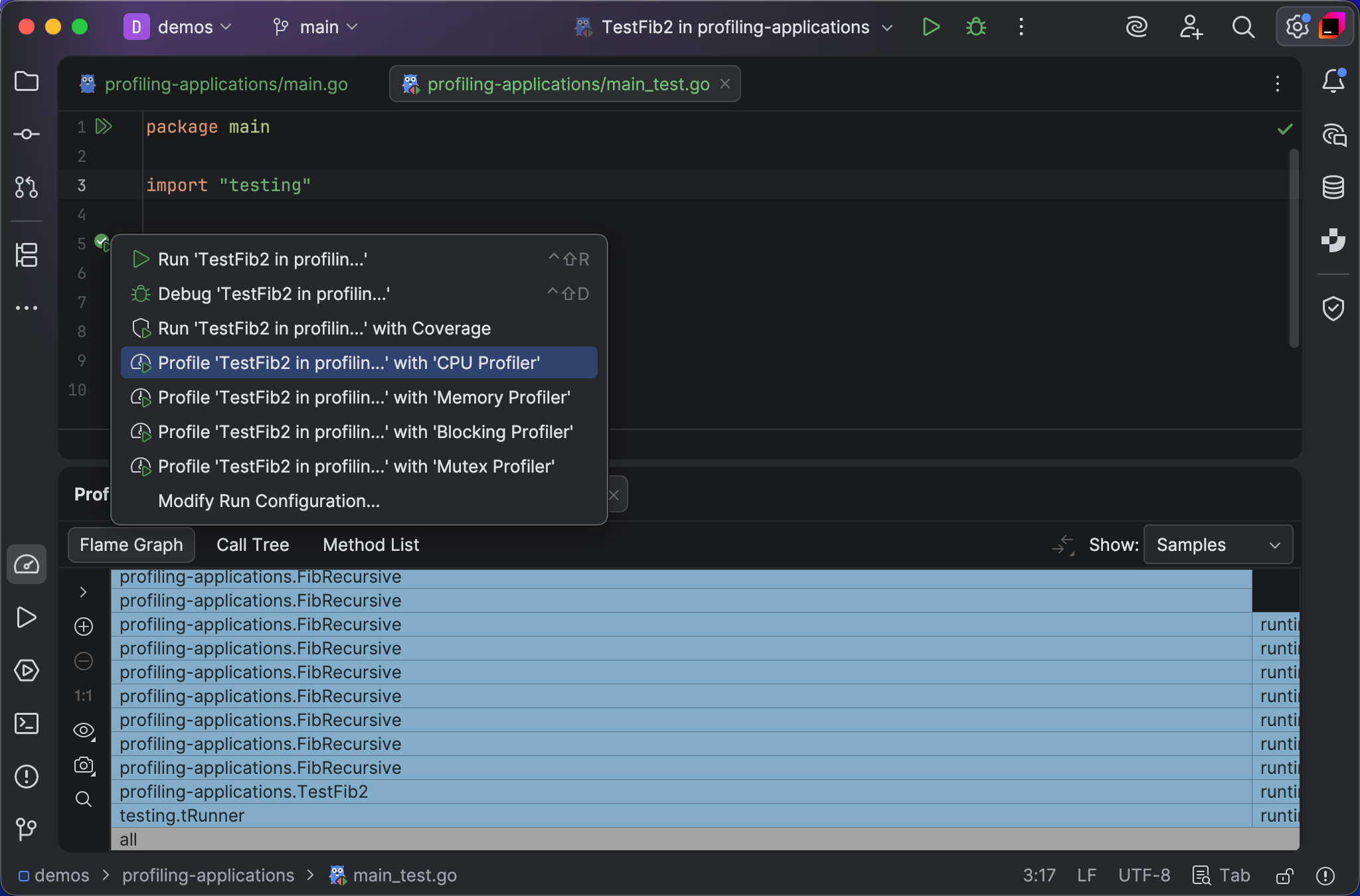

Tip: Use GoLand’s profiler and debugger to analyse the behaviour of your goroutines, eliminate leaks, and solve deadlocks.

8. Decouple code from environment

Don’t depend on OS or environment-specific details. Don’t use os.Getenv or os.Args deep in your package: only main should access environment variables or command-line arguments. Instead of taking choices away from users of your package, let them configure it however they want.

Single binaries are easier for users to install, update, and manage; don’t distribute config files. If necessary, create your config file at run time using defaults.

Use go:embed to bundle static data, such as images or certificates, into your binary:

import _ "embed" //go:embed hello.txt var s string fmt.Println(s) // `s` now has the contents of 'hello.txt'

Use xdg instead of hard-coding paths. Don’t assume $HOME exists. Don’t assume any disk storage exists, or is writable.

Go is popular in constrained environments, so be frugal with memory. Don’t read all your data at once; handle one chunk at a time, re-using the same buffer. This will keep your memory footprint small and reduce garbage collection cycles.

Tip: Use GoLand’s profiler to optimise your memory usage and eliminate leaks.

9. Design for errors

Always check errors, and handle them if possible, retrying where appropriate. Report run-time errors to the user and exit gracefully, reserving panic for internal program errors. Don’t ignore errors using _: this leads to obscure bugs.

Show usage hints for incorrect arguments, don’t crash. Rather than prompting users interactively, let them customise behaviour with flags or config.

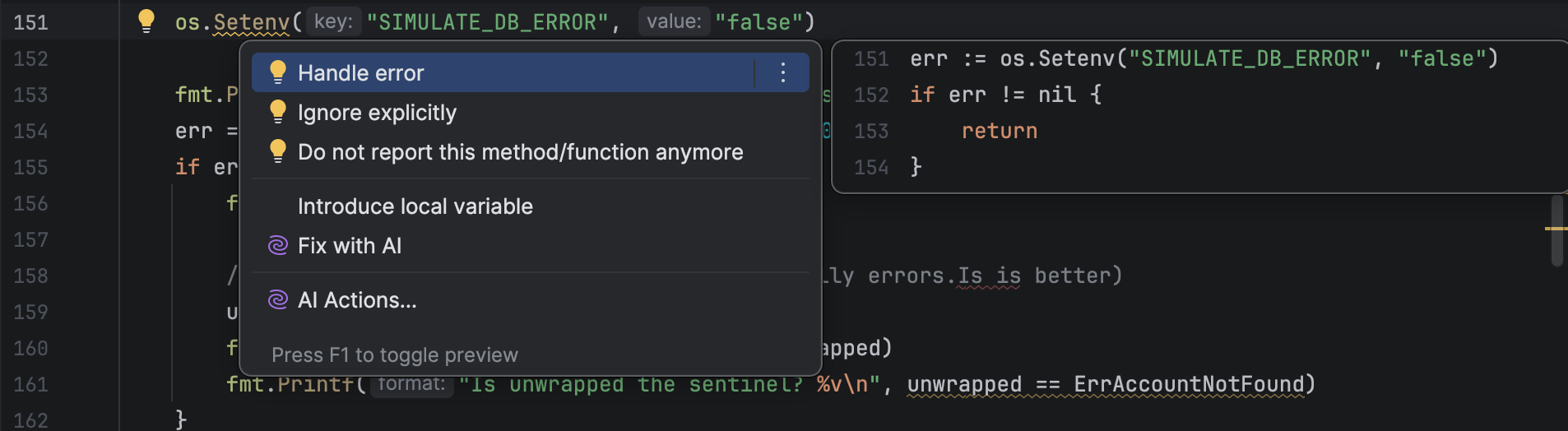

Tip: GoLand will warn you about unchecked or ignored errors, and offer to generate the handling code for you.

10. Log only actionable information

Logorrhea is irritating, so don’t spam the user with trivia. If you log at all, log only actionable errors that someone needs to fix. Don’t use fancy loggers, just print to the console, and let users redirect that output where they need it. Never log secrets or personal data.

Use slog to generate machine-readable JSON:

logger := slog.New(slog.NewJSONHandler(os.Stdout, nil))

logger.Error("oh no", "user", os.Getenv("USER"))

// Output:

// {"time":"...","level":"ERROR","msg":"oh no",

// "user":"bitfield"}

Logging is not for request-scoped troubleshooting: use tracing instead. Don’t log performance data or statistics: that’s what metrics are for.

Tip: Instead of logging, use GoLand’s debugger with non-suspending logging breakpoints to gather troubleshooting information.

Guru meditation

My mountain-dwelling guru also says, “Make it work first, then make it right. Draft a quick walking skeleton, using shameless green, and try it out on real users. Solve their problems first, and only then focus on code quality.”

Software takes more time to maintain than it does to write, so invest an extra 10% effort in refactoring, simplifying, and improving code while you still remember how it works. Making your programs better makes you a better programmer

Subscribe to GoLang Blog updates