Dancing Backwards With Go

This is a guest post from John Arundel, a Go writer and teacher who runs a free email course for Go learners. His book The Power of Go: Tests is a love letter to test-driven development in Go.

“Fred Astaire? Sure, he was great, but don’t forget Ginger Rogers did everything he did… backwards, and in high heels.”

Have you ever tried programming backwards? If not, you’re in for a treat! You won’t even need to wear high heels.

(If you want to, though, go for it—you’ll look fabulous!)

The function that never was

Suppose we want to write a Go function that checks whether a given slice is sorted (that is, its elements are in order).

For example, if the input is {1, 2, 3}, the answer should be true, because the slice is sorted. On the other hand, if the input is {3, 1, 2}, we should get false, because the slice is not sorted.

Most people would probably start writing some function IsSorted. That’s fine for Fred Astaire. Just for fun, though, shall we try tackling this problem backwards, like Ginger Rogers?

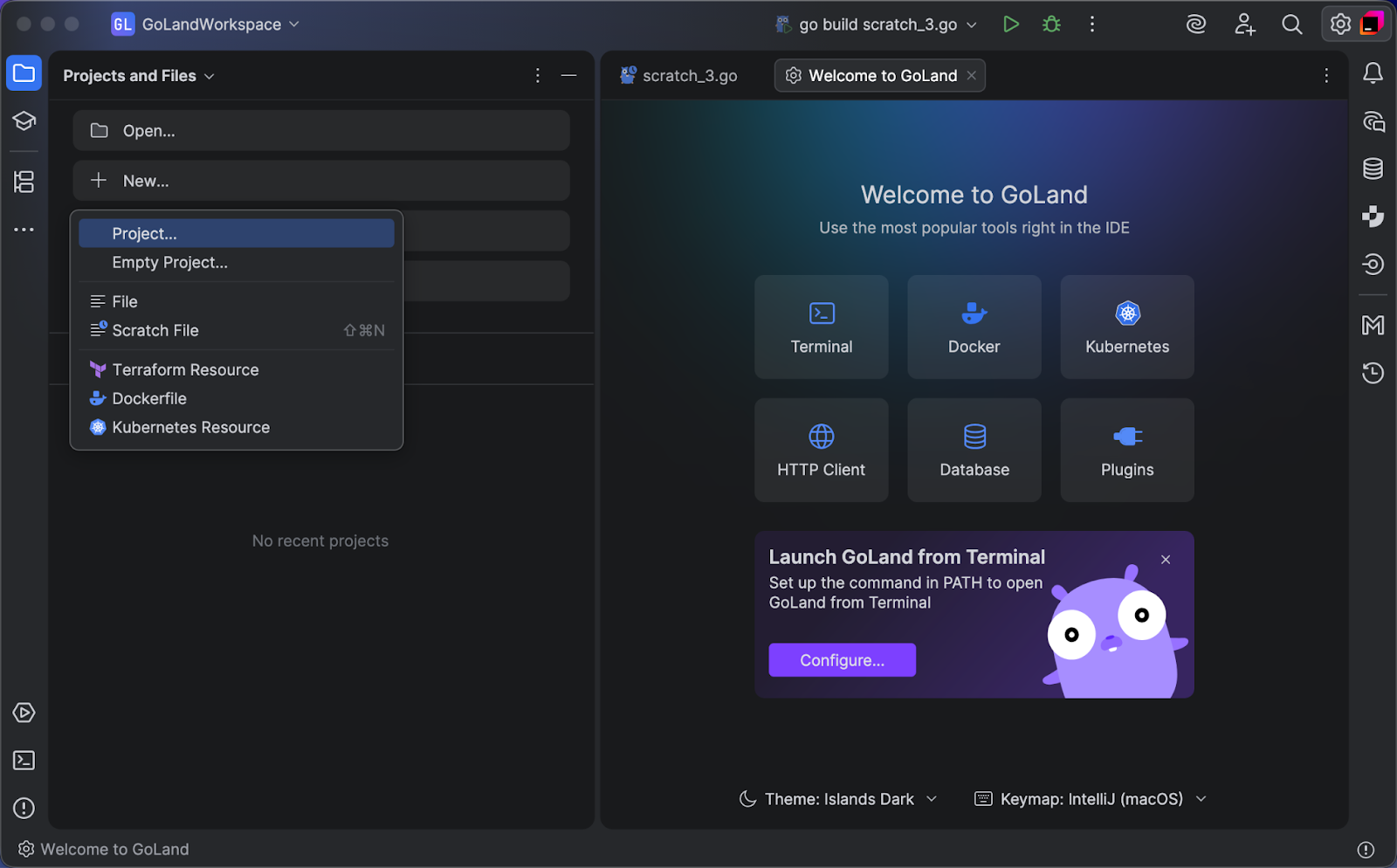

We’ll start by imagining that we already have the IsSorted function, and we’ll try to write a test for it. Once we have the test, we’ll go on to write the function.Let’s fire up GoLand and select File / New / Project… / sorted.

Next, we’ll use New / Go File to create a source file, and name it sorted_test.go.

We’ll start by declaring:

package sorted_test

All Go tests have the same signature, so the test snippet saves us writing it. We’ll type test, and press Tab to complete:

func TestName(t *testing.T) {

}

We’re invited to replace Name with a description of the behavior to test. How about:

func TestIsSorted_IsTrueForSortedSlice(t *testing.T) {

}

Sounds believable, so let’s fill in the rest:

func TestIsSorted_IsTrueForSortedSlice(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

input := []int{1, 2, 3}

if !sorted.IsSorted(input) {

t.Errorf("got false for %v", input)

}

}

If the result of calling IsSorted on this input is false, the test fails. Straightforward!

The fastest route to failure

We know IsSorted doesn’t exist yet, but before we implement it, we need to know if this test will actually detect bugs in IsSorted. That’s what tests are for, after all.

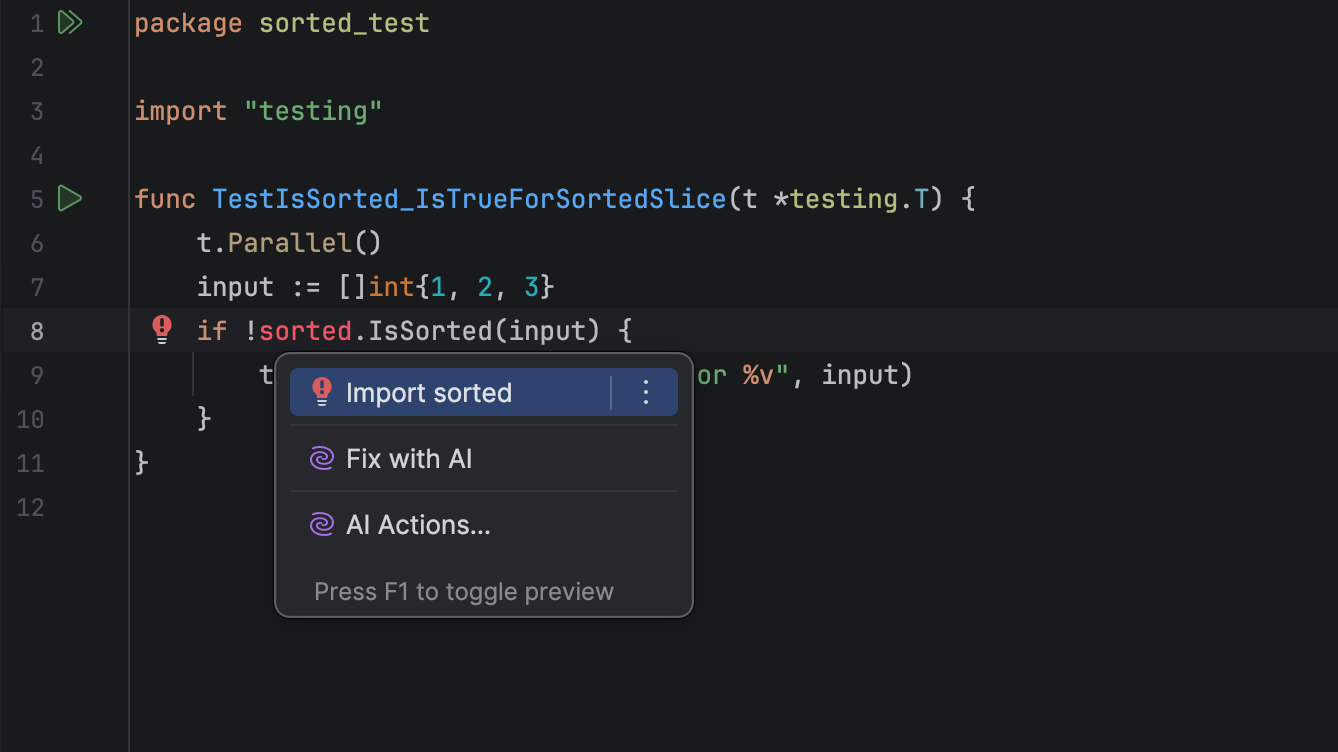

Let’s write as little code as we possibly can to get this test compiling and failing. The first problem GoLand tells us about is “Unresolved reference sorted”. Fair enough!

We need to create the sorted package, so let’s set up another new file: New / Go File / sorted.go.

Now we have a quick-fix action available in the test: import sorted. Great!

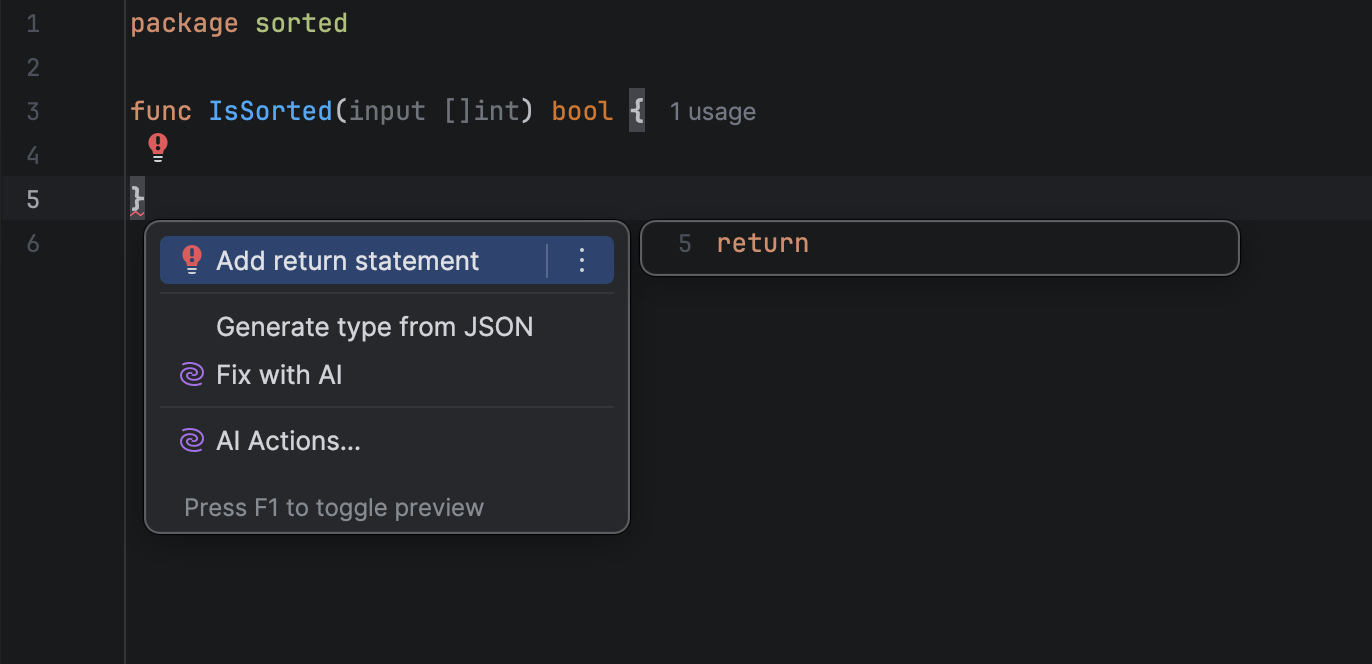

We still have an unresolved reference IsSorted, but now we can use the quick fix Create Function IsSorted. Here’s the result:

func IsSorted(input []int) bool {

}

Good start, but now GoLand says “Missing the return statement at end of function.” Here’s the quick fix: Add return statement.

Now we have:

func IsSorted(input []int) bool {

return

}

Almost there, but now we have the error “not enough arguments to return.” Quick fix again: Add missing return values.

func IsSorted(input []int) bool {

return false

}

“But this won’t work!” I hear you wail. “It always returns false no matter what the input!”

Your wailing is on point, dear reader, but remember, we want a non-working implementation, and now we have one. This is the perfect time to check if our test will actually detect a bug in IsSorted—for instance, that it always returns false!

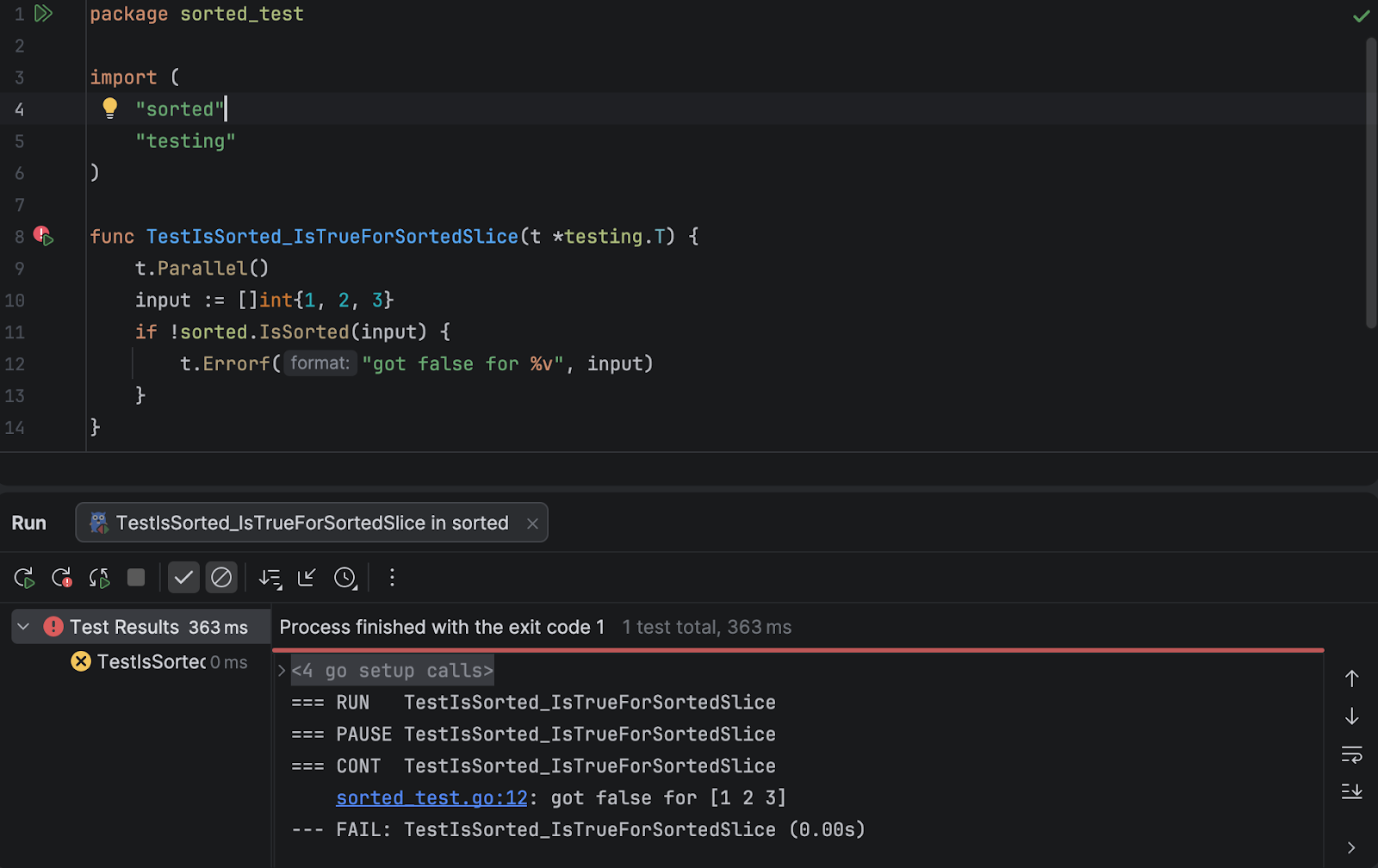

Let’s click the green triangle next to the test name to run the test. We assume it will fail, but you never know—that’s why we check:

sorted_test.go:12: got false for [1 2 3] --- FAIL: TestIsSorted_IsTrueForSortedSlice (0.00s)

Success! (I said this was backwards.)

Cranking up the difficulty

We could trivially change IsSorted to return true instead of false to make this pass, but that doesn’t really get us anywhere. IsSorted needs to be able to distinguish between sorted and unsorted slices, not just return a fixed value.

We want two tests, for two different behaviours: that IsSorted is true for sorted inputs, and that it’s false for unsorted ones.

func TestIsSorted_IsTrueForSortedSlice(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

input := []int{1, 2, 3}

if !sorted.IsSorted(input) {

t.Errorf("got false for %v", input)

}

}

func TestIsSorted_IsFalseForUnsortedSlice(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

input := []int{1, 3, 2}

if sorted.IsSorted(input) {

t.Errorf("got true for %v", input)

}

}

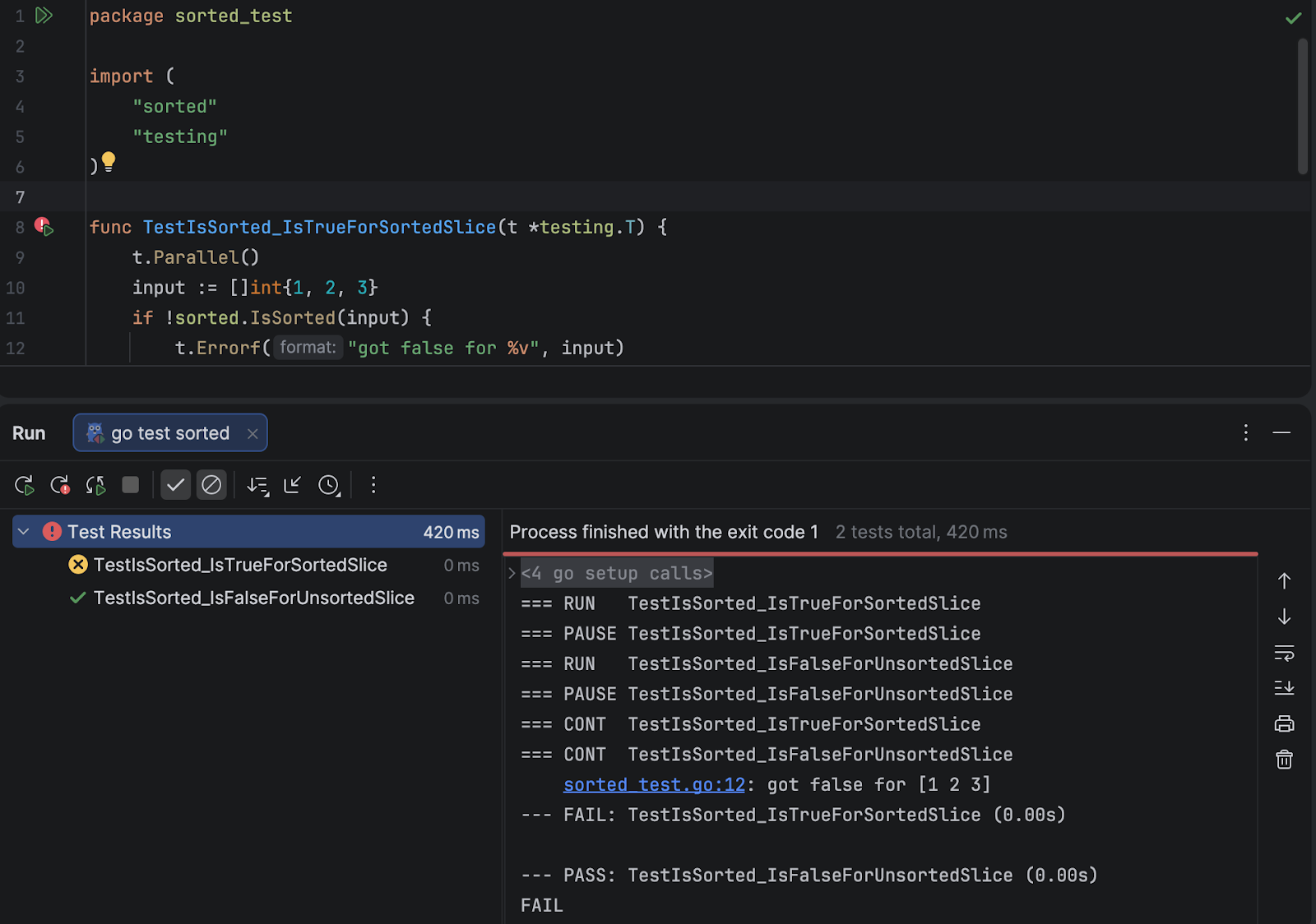

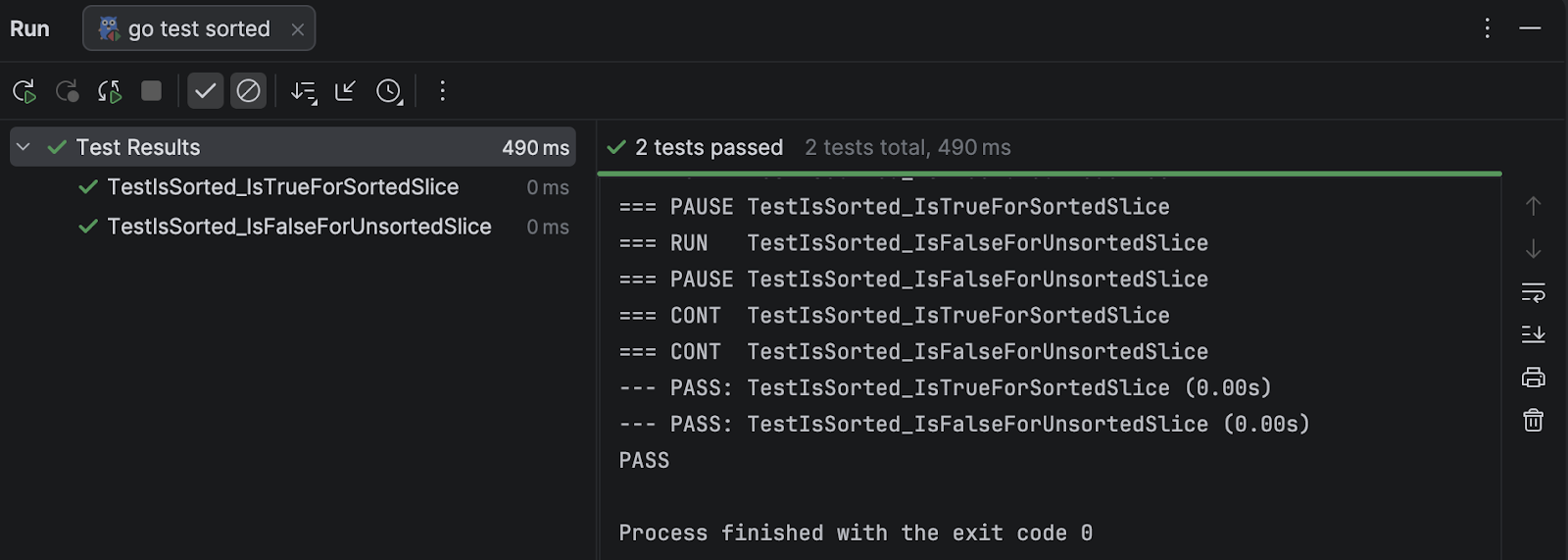

A fixed-value implementation could pass one test or the other, but not both. Let’s prove it, using the Ctrl-Shift-R shortcut to run all tests in this file:

How little work do you think we can do to get both tests passing?

Baby’s first steps

If any elements are not in order, then at some point we’ll encounter a number that’s smaller than the previous one. The simplest, dumbest way I can think of to detect that is:

func IsSorted(input []int) bool {

prev := 0

for _, v := range input {

if v < prev {

return false

}

}

return true

}

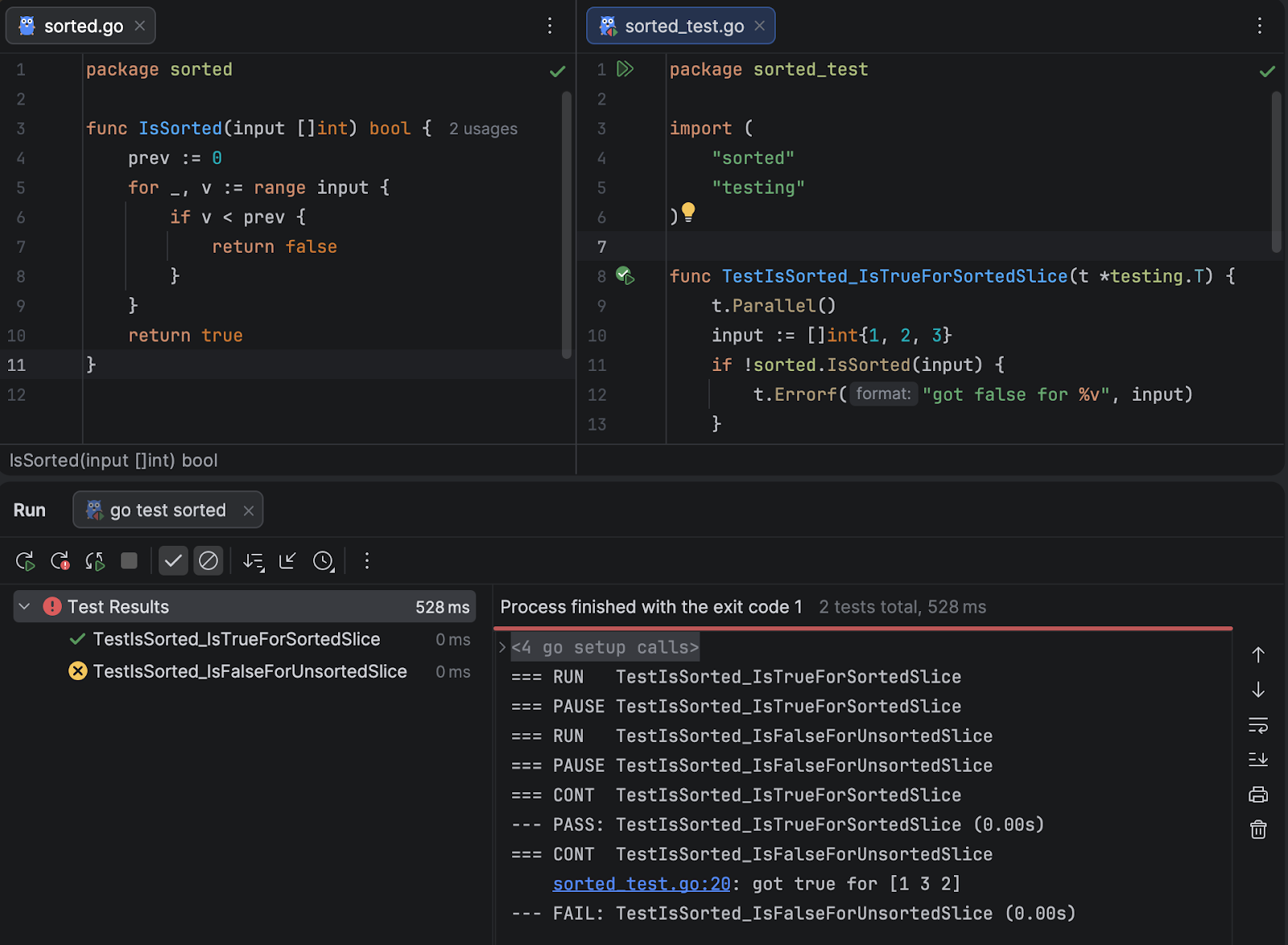

It seems reasonable, but I could stare at this code all day and not be sure whether it’s correct or not. Let’s check:

=== FAIL: TestIsSorted_IsFalseForUnsortedSlice

sorted_test.go:20: got true for [1 3 2]

Oops. I forgot to update prev with each new number (not enough coffee today). Let’s add a prev = v to the loop:

func IsSorted(input []int) bool {

prev := 0

for _, v := range input {

if v < prev {

return false

}

prev = v

}

return true

}

This passes both tests now, but is it really correct? Again, we could have a staring contest with this code looking for bugs, and we might find some, or we might not.

The backwards programmer’s approach, though, is to stare at the tests instead. Can we think of some more test cases that might trip up a buggy implementation of IsSorted?

What about a slice that contains repeated numbers, for example?

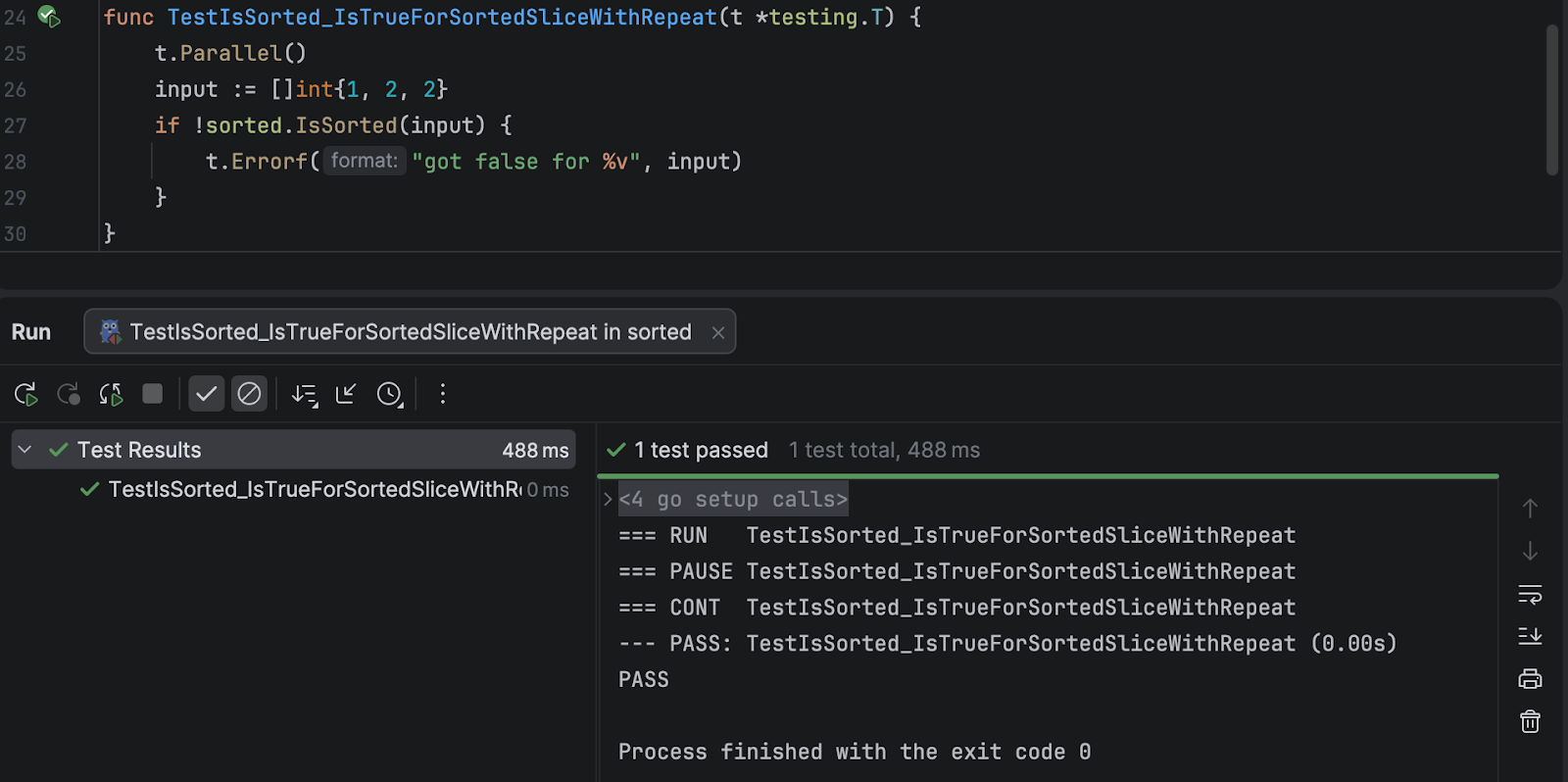

func TestIsSorted_IsTrueForSortedSliceWithRepeat(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

input := []int{1, 2, 2}

if !sorted.IsSorted(input) {

t.Errorf("got false for %v", input)

}

}

This passes, which is encouraging. But I notice that the test logic is the same for all our “sorted” tests, so let’s combine them into a single table test.

Cases on the table

GoLand can write this table test for us, if we right-click on the IsSorted function and select Generate / Test for function:

func TestIsSorted(t *testing.T) {

type args struct {

input []int

}

tests := []struct {

name string

args args

want bool

}{

// TODO: Add test cases.

}

for _, tt := range tests {

t.Run(tt.name, func(t *testing.T) {

if got := sorted.IsSorted(tt.args.input); got != tt.want {

t.Errorf("IsSorted() = %v, want %v", got, tt.want)

}

})

}

}

Not bad, but this generated code is just a suggestion: we don’t have to follow it slavishly. Let’s make a few small tweaks:

- We’ll run the test in parallel

- We’ll organise the test cases as a map, keyed by name

- We don’t need to specify

wantevery time, because it’s alwaystruein this test

So:

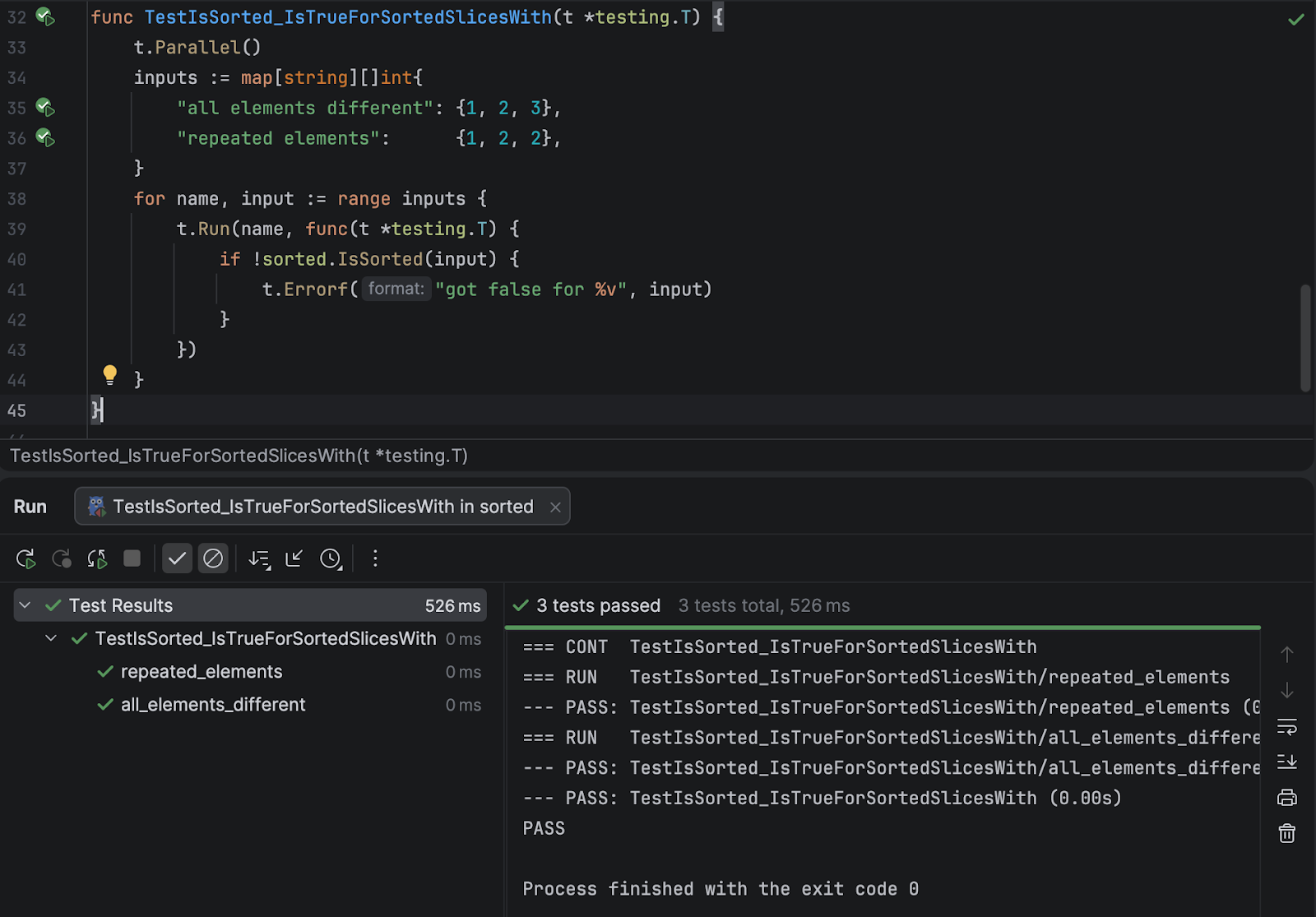

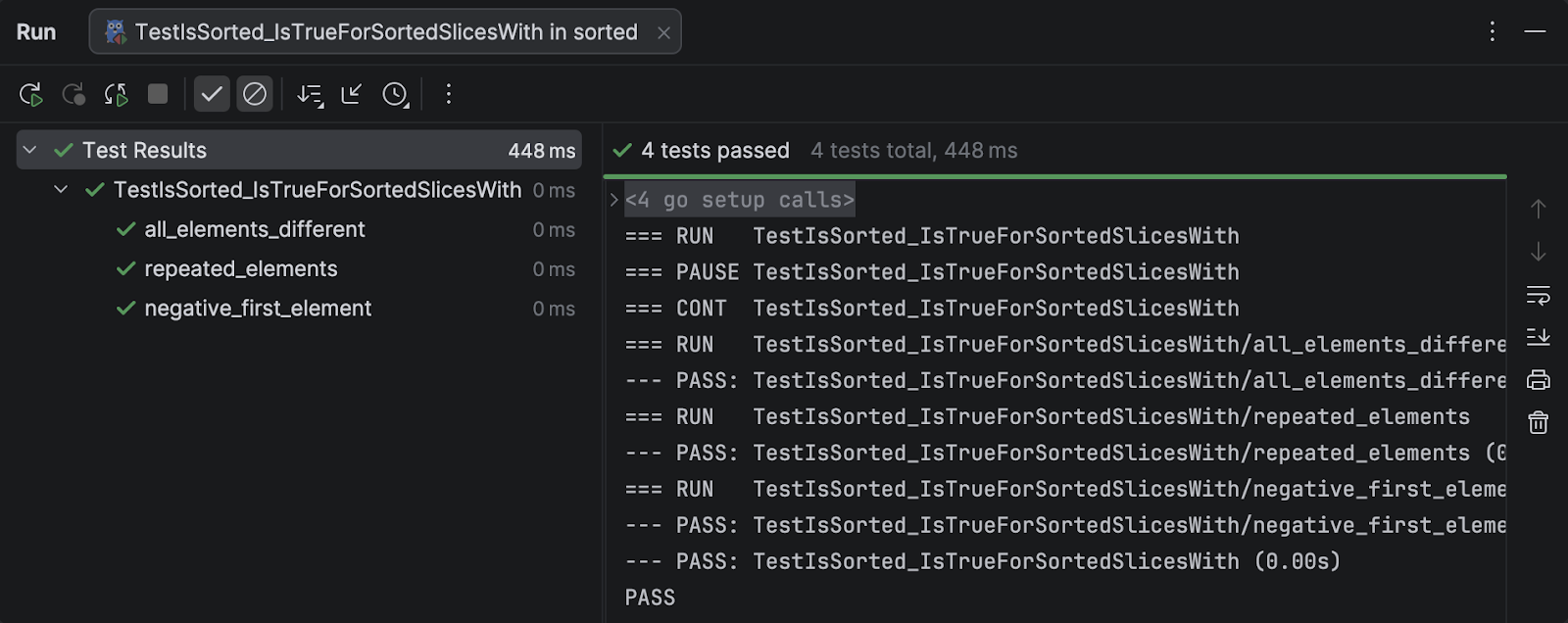

func TestIsSorted_IsTrueForSortedSlicesWith(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

inputs := map[string][]int{

"all elements different": {1, 2, 3},

"repeated elements": {1, 2, 2},

}

for name, input := range inputs {

t.Run(name, func(t *testing.T) {

if !sorted.IsSorted(input) {

t.Errorf("got false for %v", input)

}

})

}

}

Using t.Run turns each case into a named subtest, and all our subtests can share the same function body, which simplifies things.

This replaces the two old IsTrue tests, so now let’s add another table test for IsFalse:

func TestIsSorted_IsFalseForUnsortedSlicesWith(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

inputs := map[string][]int{

"all elements different": {1, 3, 2},

"repeated elements": {3, 2, 2},

}

for name, input := range inputs {

t.Run(name, func(t *testing.T) {

if sorted.IsSorted(input) {

t.Errorf("got true for %v", input)

}

})

}

}

Looking good. Time for a well-earned break, I think. Would you care for some tea and cake?

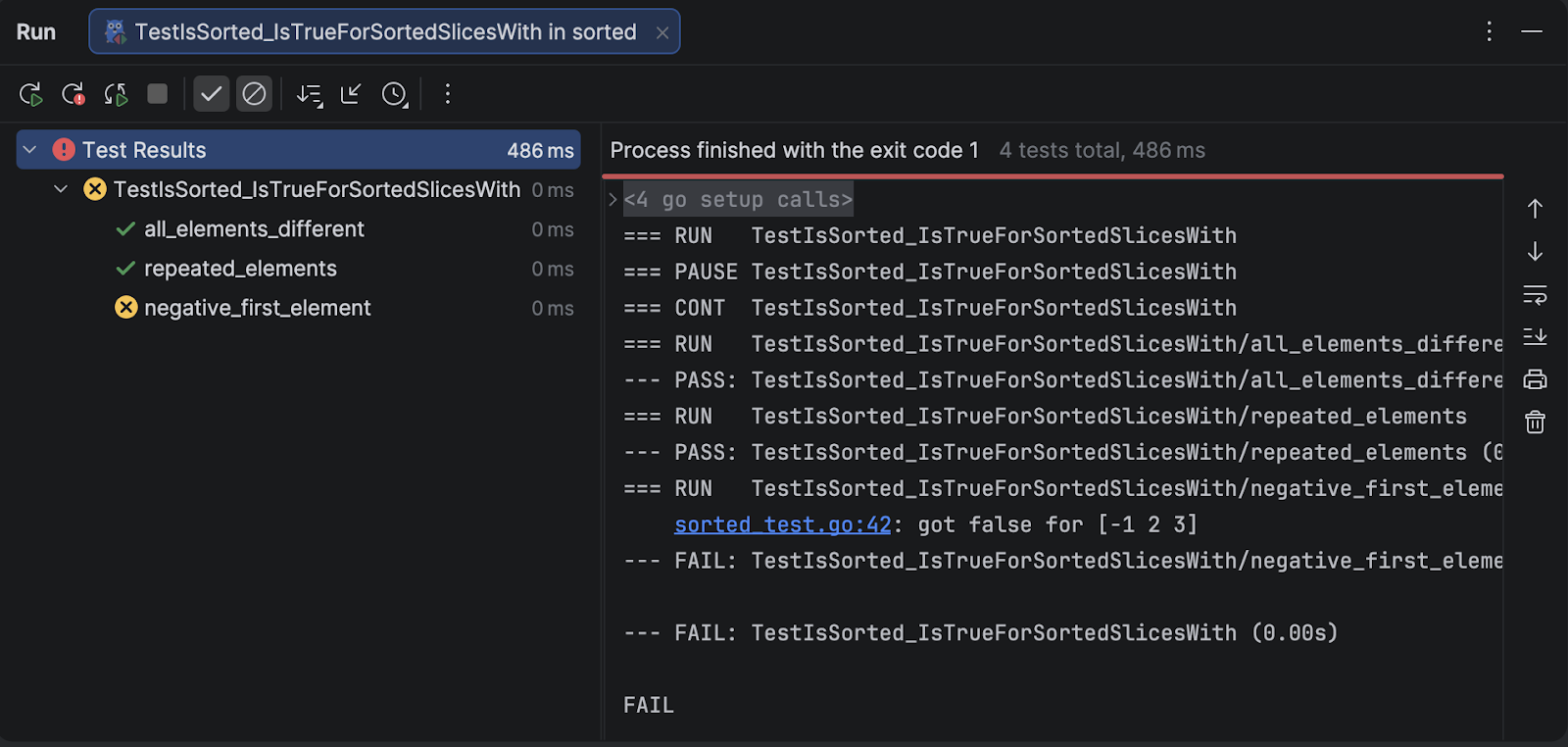

Don’t be so negative!

While I was nibbling at a moist, fudgy chocolate brownie just now, I thought: prev starts at zero, but what if the first element is negative? Then we’d wrongly return false for a sorted slice, because v < prev. Yikes!

Your conventional programmer—Fred Astaire, if you like—would jump straight into fixing IsSorted. But we’re backwards programmers, so we’ll use the Ginger Rogers technique: first write a failing test, then make it pass.

func TestIsSorted_IsTrueForSortedSlicesWith(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

inputs := map[string][]int{

"all elements different": {1, 2, 3},

"repeated elements": {1, 2, 2},

"negative first element": {-1, 2, 3},

}

...

This fails as expected:

Now we can fix it. Let’s initialize prev to the first element of input and then loop over the remaining elements:

func IsSorted(input []int) bool {

prev := input[0]

for _, v := range input[1:] {

if v < prev {

return false

}

prev = v

}

return true

}

And:

Oh glory be, oh happy day! We can ship the package to production and go out for our team pizza night (extra pepperoni on mine, please).

Later that same week…

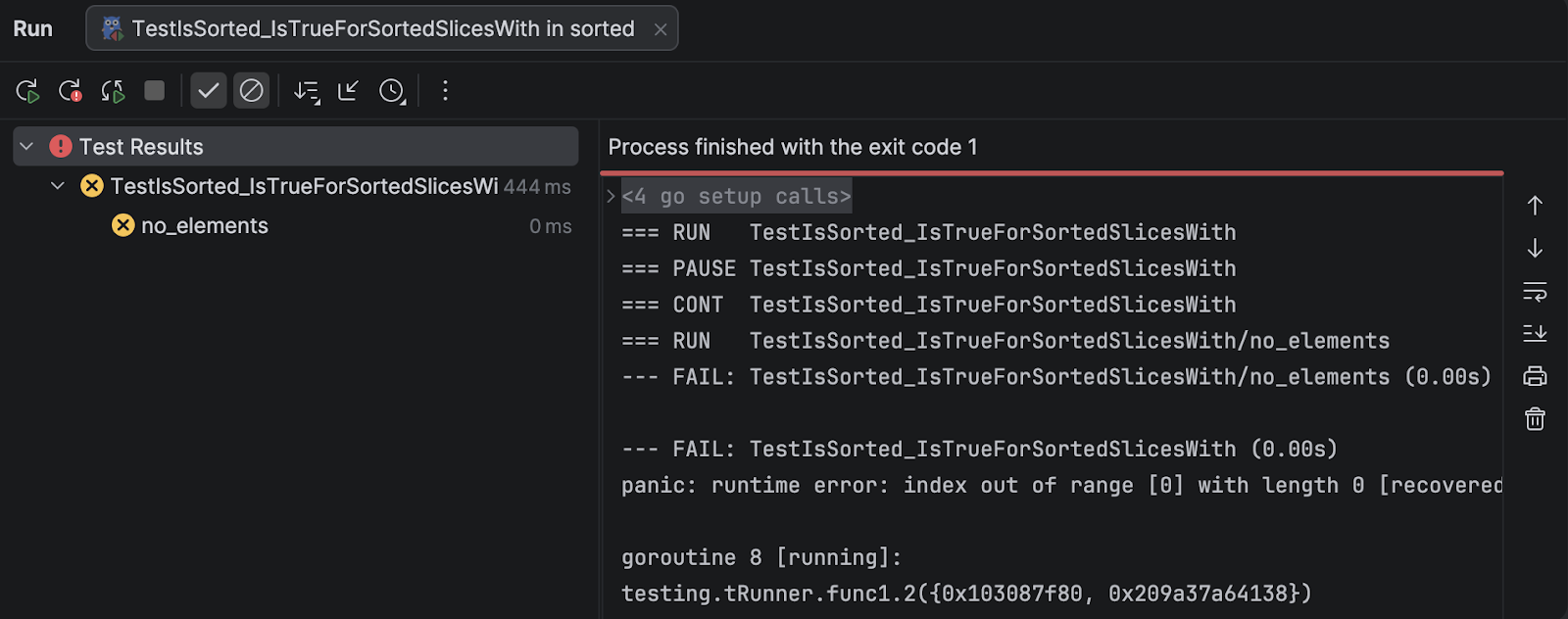

Well, everything was fine for a few days, but then a bug report came in from a customer: IsSorted panicked when they called it with an empty slice (oh dear).

Well, we can fix this—backwards! Let’s add the customer’s “no elements” test case to our table:

func TestIsSorted_IsTrueForSortedSlicesWith(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

inputs := map[string][]int{

"all elements different": {1, 2, 3},

"repeated elements": {1, 2, 2},

"negative first element": {-1, 2, 3},

"no elements": {},

}

...

This should reproduce the bug report:

Next, we’ll locate the panic using the stack trace:

sorted.IsSorted(...)

/yumyum/cake/yesplease/sorted/sorted.go:4

This is a link, so clicking the filename teleports us straight to the offending line:

prev := input[0]

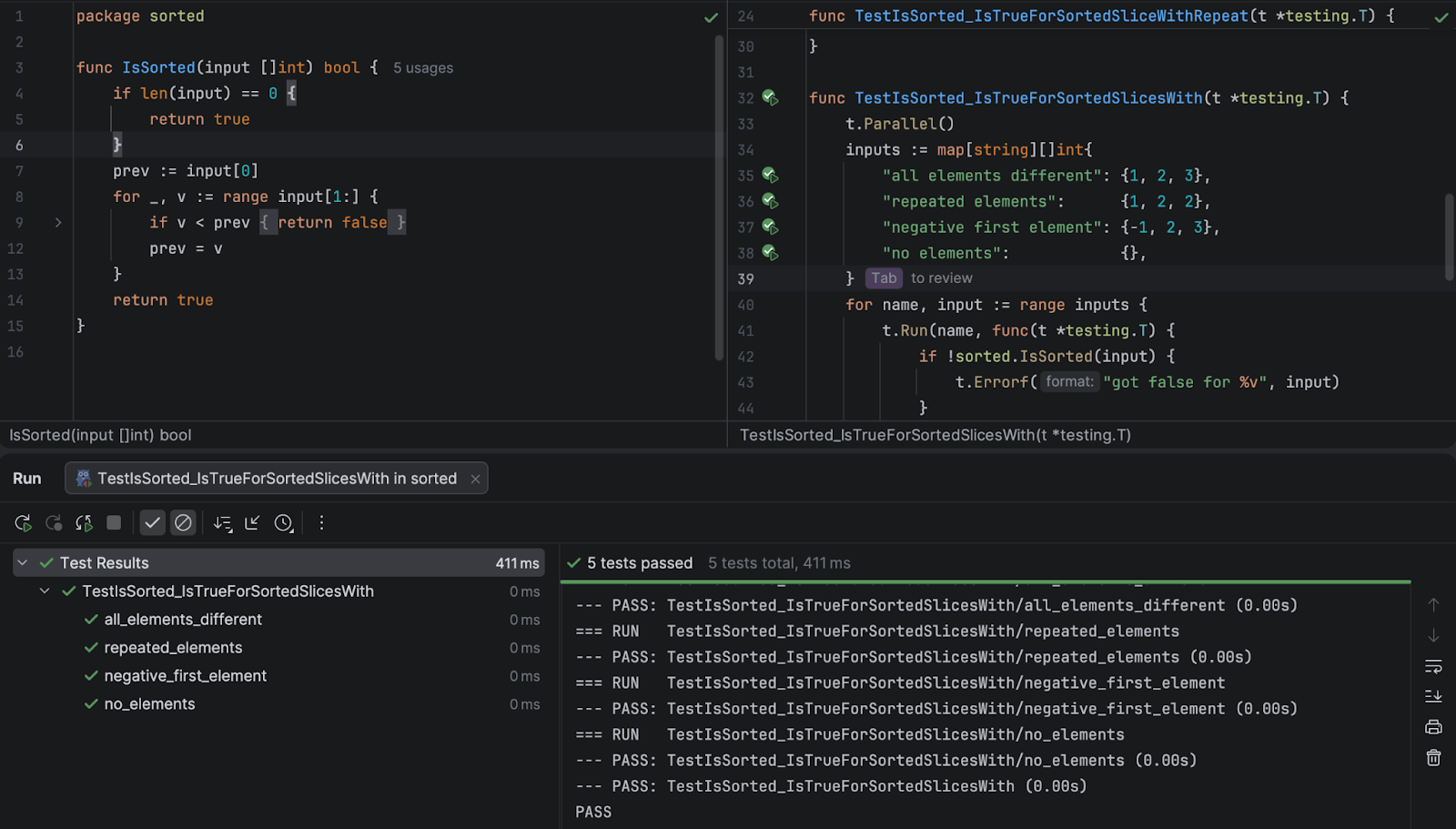

An empty slice has no elements, hence the panic. But it is sorted, so we can simply return true straight away in this case:

if len(input) == 0 {

return true

}

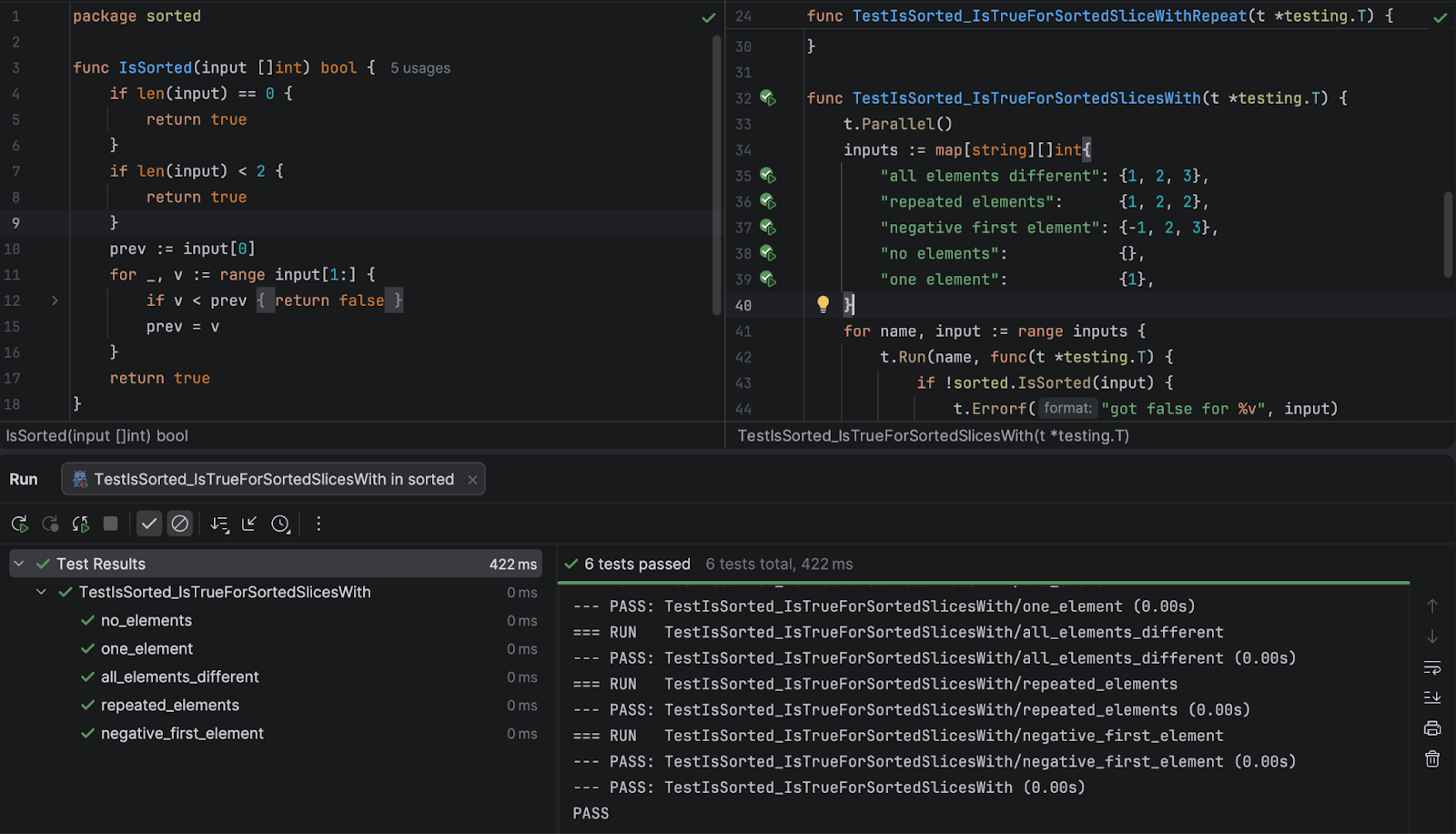

And while we’re here, let’s handle a one-element slice the same way. New test case:

func TestIsSorted_IsTrueForSortedSlicesWith(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

inputs := map[string][]int{

"all elements different": {1, 2, 3},

"repeated elements": {1, 2, 2},

"negative first element": {-1, 2, 3},

"no elements": {},

"one element": {1},

}

...

A small tweak to the function:

if len(input) < 2 {

return true

}

Tests are passing, and customers are happy. Another win for backwards programming!

Cutting out the calories

A little while later, a new member of the team, Alyssa, is looking at our current version of IsSorted:

func IsSorted(input []int) bool {

if len(input) < 2 {

return true

}

prev := input[0]

for _, v := range input[1:] {

if v < prev {

return false

}

prev = v

}

return true

}

“You know,” she says, “there’s a function for this in the standard library. I think we could replace all this code with just…”

return slices.IsSorted(input)

Huge if true! Well, we know exactly how to find out: run the tests.

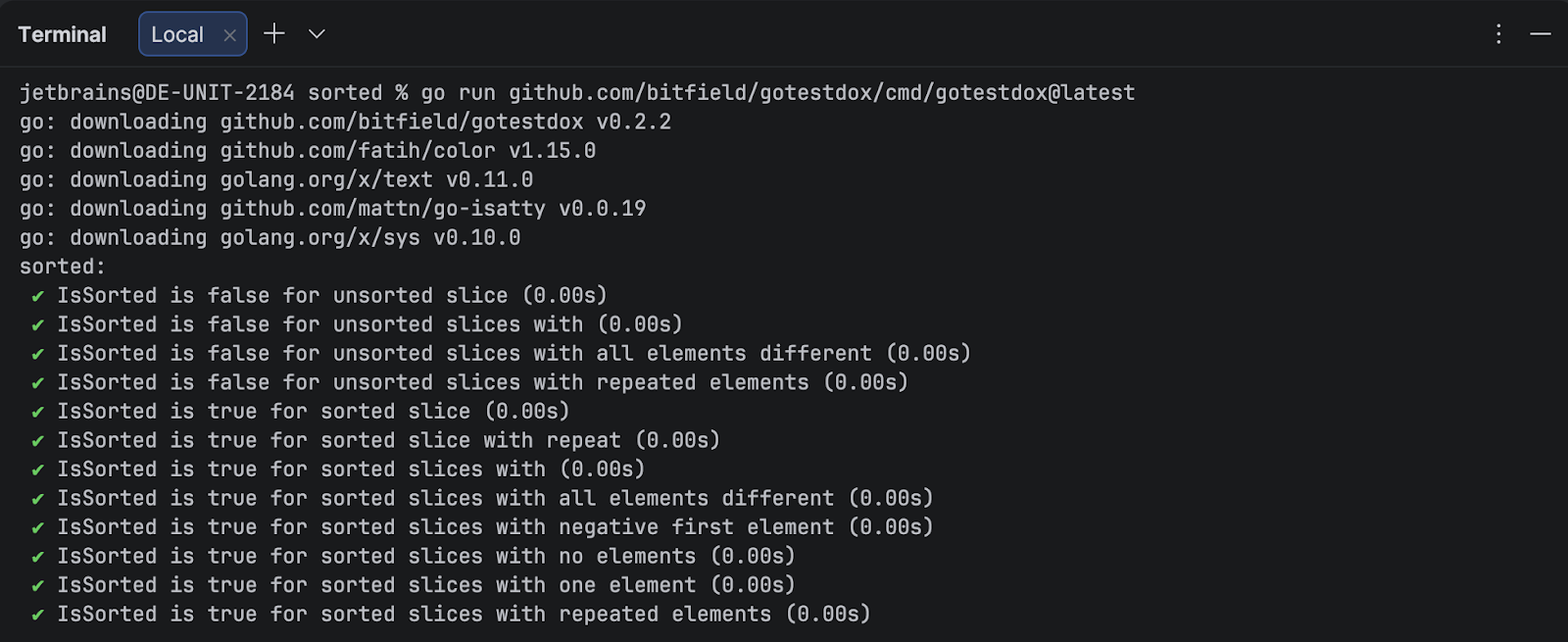

Just for fun, let’s use the gotestdox tool, which both runs the tests and prints their names as English sentences. “Tests as docs”, if you like.

go run github.com/bitfield/gotestdox/cmd/gotestdox@latest

Wonderful! This is exactly the kind of radical refactoring idea we hoped you’d bring to the team, Alyssa P. Hacker. And backwards programming helped make it safe: by writing our tests first, we made sure that any new code is always covered by tests.

The way forward?

So that’s backwards programming. Once you’ve tried it, it doesn’t really seem so backwards after all, does it?

Next time you have a feature to add or a bug to fix, then, why not try doing the backwards quickstep yourself? It’s as easy as “red, green, refactor”:

- Add a failing test (“red”)

- Make it pass (“green”)

- Tidy up, optimise, and check that all tests still pass (“refactor”)

Just remember to always look where you’re going, and try not to trip over your own feet. Shall we dance?

Subscribe to GoLang Blog updates