Upgrade Your Testing with Behavior-Driven Development

BDD? Why should I care?

Back in the day, I used to write terrible code. I’m probably not the only one who started out writing terrible PHP scripts in high school that just got the job done. For me, the moment that I started to write better code was the moment that I discovered unit testing. Testing forced me to properly organize my code, and keep classes simple enough that testing them in isolation would be possible. Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) testing has the potential to do the same at a program level rather than individual classes.

A common problem when making software is that different people have different opinions on what the software should do, and these differences only become apparent when someone is disappointed in the end. This is why in large software projects, it’s commonplace to spend quite a bit of effort getting the requirements right.

If you’re making a small personal project, BDD can help you by forcing you to write down what you want your program to do before you start programming. I speak from experience when I say this helps you finish your projects. Furthermore, in contrast to regular unit testing you get separation of concerns between your test scenario and your test code. What programmer doesn’t become excited about separation of concerns? This one sure does :D

The real value of BDD arises for those of you who do contract work for small businesses, and even those with small to medium-sized open source projects, wouldn’t it be useful to have a simple way to communicate exactly what the software should do to everyone involved?

Okay, so how do I get better software?

Behavior-driven development is just that: development which is driven by the behavior you want from your code. Those of you who do Agile probably know the “As a <user>, I want <behavior>, so that <benefit>” template. In BDD, a similar template is proposed: “In order to <benefit>, as a <user>, I want <behavior>”. In this template the goal of your feature is emphasized, so let’s do some truth in advertising here:

In order to show off PyCharm’s cool support for BDD

As a Product Marketing Manager at JetBrains

I want to make a reasonably complex example project that shows how BDD works

This is still rather vague, so let’s come up with an actual example project:

Feature: Simulate a basic car

To show off how BDD works, let’s create a sample project which takes the classic OO car example, and supercharges it.

The car should take into account: engine power, basic aerodynamics, rolling resistance, grip, and brake force.

To keep things somewhat simple, the engine will supply constant power (this is not realistic, as it results in infinite Torque at zero RPM)

A key element of BDD is using examples to illustrate the features, so let’s write an example:

Scenario: The car should be able to brake

The UK highway code says that worst case scenario we need to stop from 60 mph (27 m/s) in 73 m

Given that the car is moving at 27 m/s

When I brake at 100% force

And 10 seconds pass

Then I should have traveled less than 73 meters

By writing this example, it becomes clear that our code will need to be aware of time passing, keep track of the car’s speed, distance traveled, and the amount of braking that is applied at a given point in time.

If you have complex examples, or want to check a couple of similar examples, you can use ASCII tables in your feature file to do this. To keep this blog post to a reasonable length, I won’t discuss those, but you can check the code on GitHub to see an example, or read more in the behave docs.

Feature files and steps

In BDD, you first write a feature file which describes the feature, with examples that outline how the feature is supposed to behave in certain cases. Using BDD tools, you should then be able to test the scenarios in these feature files automatically.

To make the scenarios testable, they need to be structured in a specific way:

Given a precondition

When an action

Then a postcondition

So let’s take our feature from above, add some scenarios, and create a feature file which we will put in a ‘features’ directory in our project. As always, you can follow along with the code on GitHub.

Most BDD tools also support starting a sentence in the scenario with ‘And’ which will behave the same way as the sentence before it, so ‘Given, And’ will behave just like ‘Given, Given’.

Next you define steps in code, which execute the test. For this, we need a BDD tool. In Python a good choice of tool is behave. An important note here, the newest version of Behave at the time of writing (Behave 1.2.5) is not compatible with Python 3.6, so please use Python 3.5!

If you’re a pytest user, you may want to give pytest-bdd a shot: check out our blog post on pytest-bdd.

If at this point we run behave, it will detect our feature and scenarios, but tell us that all of our steps are still undefined. So let’s have a look at how we can make the scenario testable. Let’s implement the “car should be able to brake” scenario:

@given("that the car is moving at (?P<speed>\d+) m/s")

def step_impl(context, speed):

context.car.speed = float(speed)

@when("I brake at (?P<brake_force>\d+)% force")

def step_impl(context, brake_force):

context.car.set_brake(brake_force)

@step("(?P<seconds>\d+) seconds? pass(?:es)?")

def step_impl(context, seconds):

context.car.simulate(seconds)

@then("I should have traveled less than (?P<distance>\d+) meters")

def step_impl(context, distance):

assert_that(context.car.odometer, less_than(float(distance)))

This code goes into a file in the /features/steps folder. By writing the test code first you’re forced to think about what you would like your eventual application code to look like. Also note that we’re using PyHamcrest (a library which provides better matchers between expected and actual values) here to define the assertions, as they give us a lot more helpful error messages than regular assertions when they fail.

Running Behave Tests

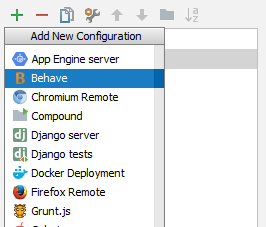

To run our Behave tests in PyCharm, we need to add a Behave run configuration. To do this, just add a run configuration like any other, but select Behave:

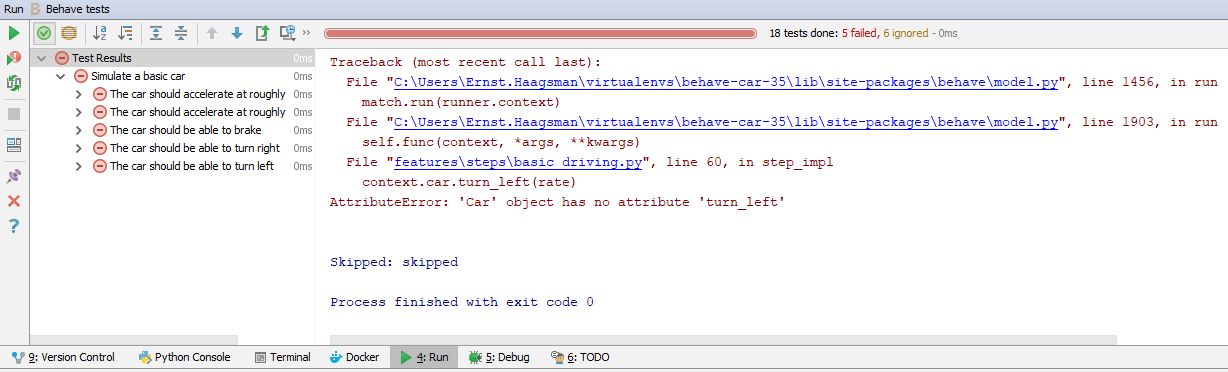

You don’t need to configure anything else. If you run behave without specifying anything, Behave will execute all the feature files in your project. So let’s run it:

We can see that our feature is tested, using all of the scenarios that we’ve defined for our feature. As we haven’t written any code yet, all tests fail, and everything is red :( So let’s write some code and see what it looks like after we finish:

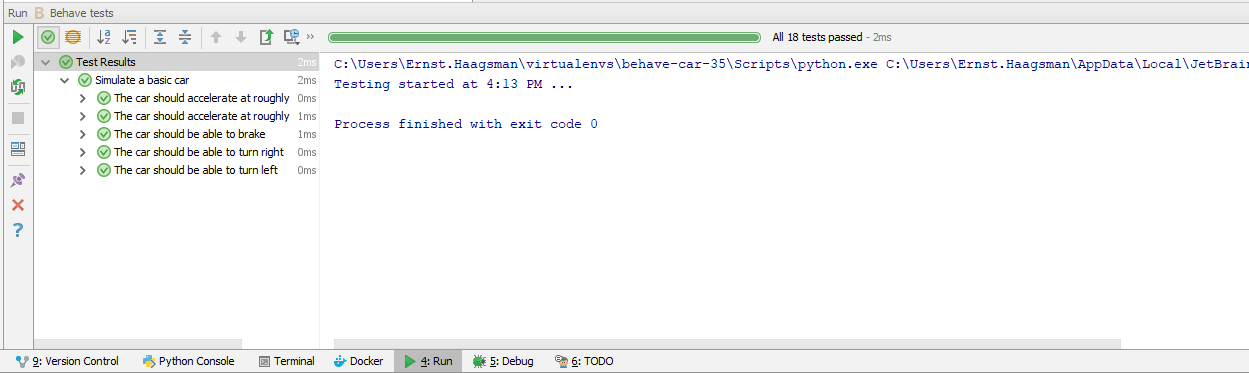

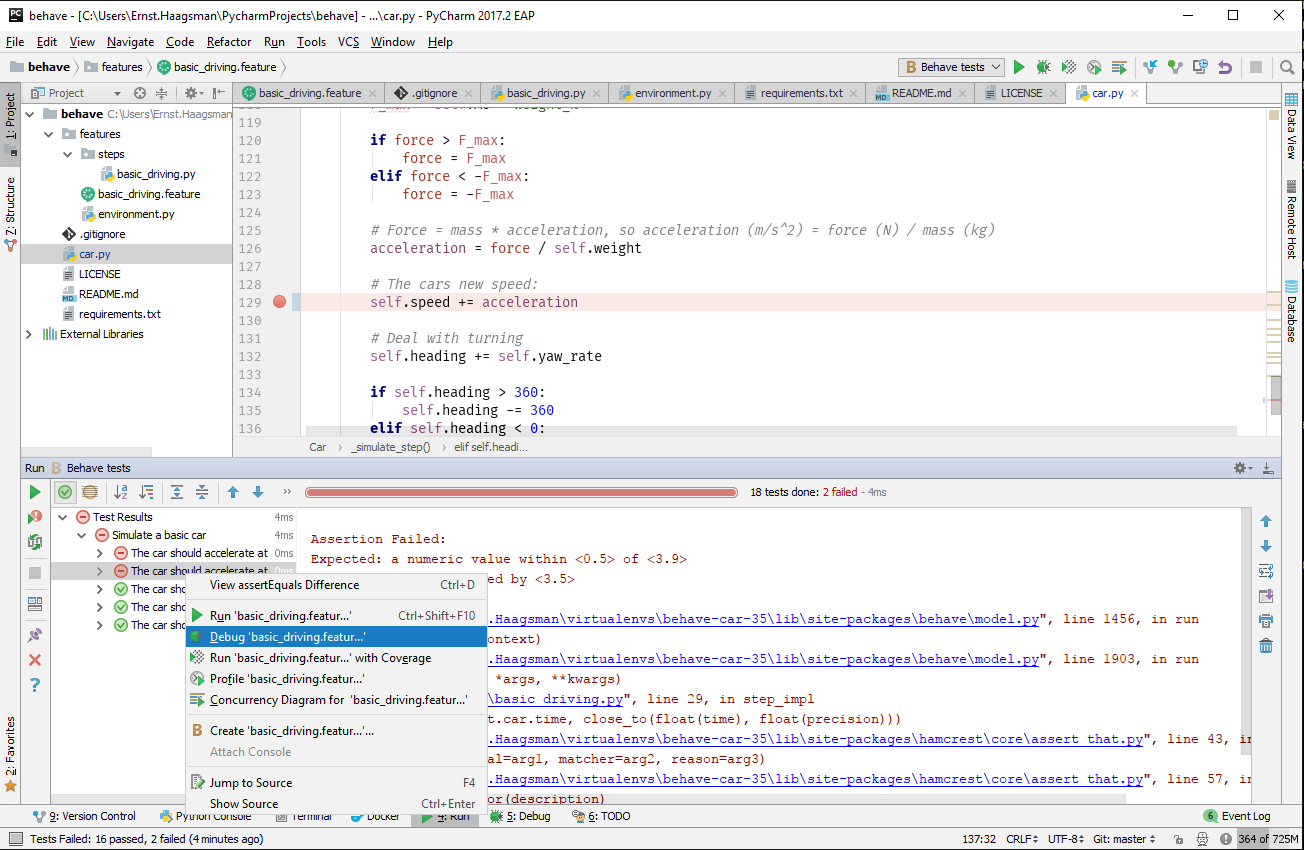

Much better, right? Now let’s say we made a mistake, for example, if we forgot the deltaT term when adding the acceleration to the car’s speed, we will see that the acceleration tests fail. Of course PyCharm makes it easy for us to put a breakpoint in the code, and then debug our test:

To Conclude

BDD is a tool which has the potential to make your software better. This blog post was a very short introduction, and I hope it’s been enough to get some of you interested in giving it a shot! Please let me know in the comments if you’d like to read more about BDD in the future.

Subscribe to PyCharm Blog updates