Upsource

Code Review and Project Analytics

Code Review As A Gateway

We’ve talked a lot about what to look for in a Code Review, but we haven’t covered the process at all. There are many different reasons to perform code reviews in your team or organisation, and the process you choose should be driven by what you’re trying to achieve with the reviews.

The first example we’re going to explore is Code Review as a Gateway. In this process, a developer picks up or is assigned a task, implements the code to the best of his/her ability, and when s/he’s “finished”, submits it for review. The reviewer checks the code and, if everything is OK, the code is merged into the main development branch.

This was a fairly typical approach in organisations with a formal software development process – each stage had a gateway which needed one or more people to sign off to say the work had been done correctly. In these days of more collaborative, agile approaches, however, this is less common, particularly if the team is colocated. But it is a similar process to that of GitHub pull requests, so that’s the example we’re going to explore.

The process

In this example, we’re working on an open source project hosted on GitHub. I have decided to pick up one of the issues listed. Generally it’s a good idea to mention on the mailing list, or discuss with the project owner that you want to work on this, and maybe have a conversation on the approaches you want to take. The project owner may be able to point you to some example code that fits the pattern they want, and/or point out some gotchas to be aware of.

I’ll go away and implement the fix or feature. If I have doubts I’ll probably chat to the owner either on the ticket or via chat/email, but eventually I’ll submit a pull request with what I think is the complete working code.

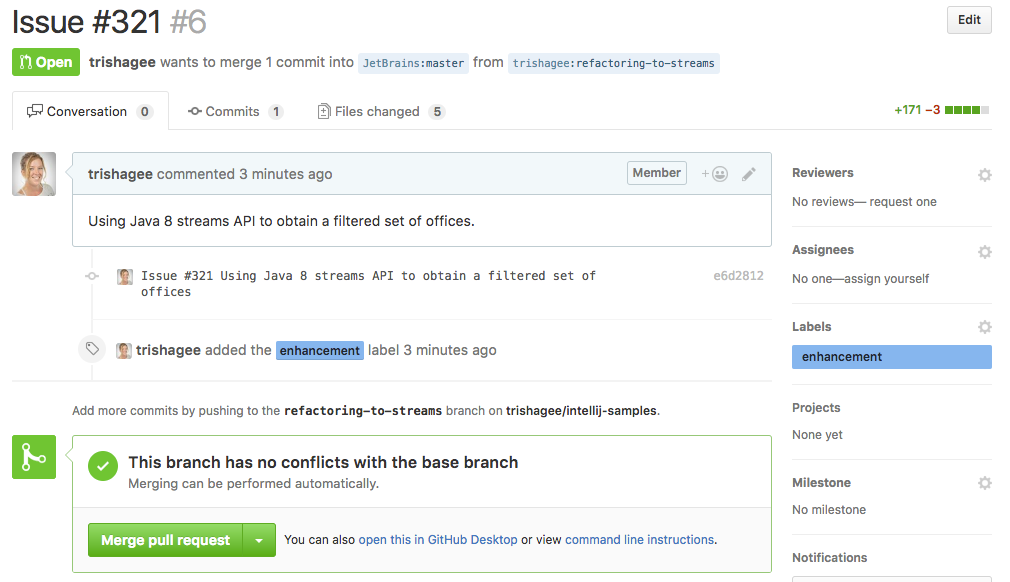

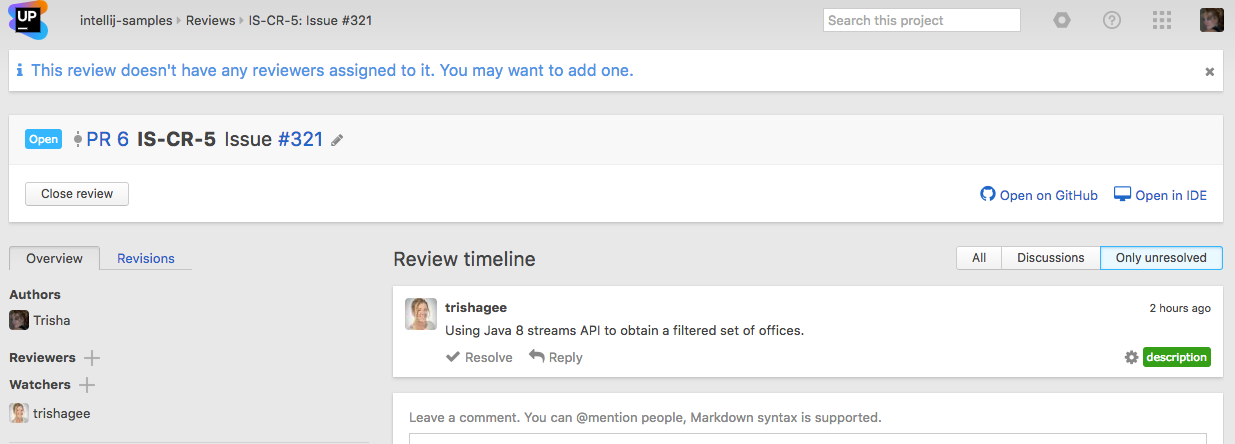

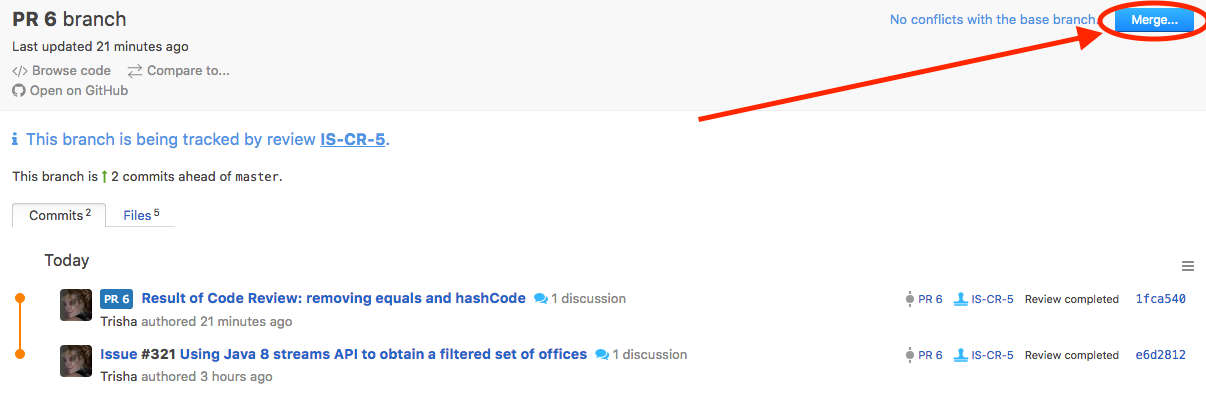

In Upsource, pull requests are automatically converted into Code Reviews:

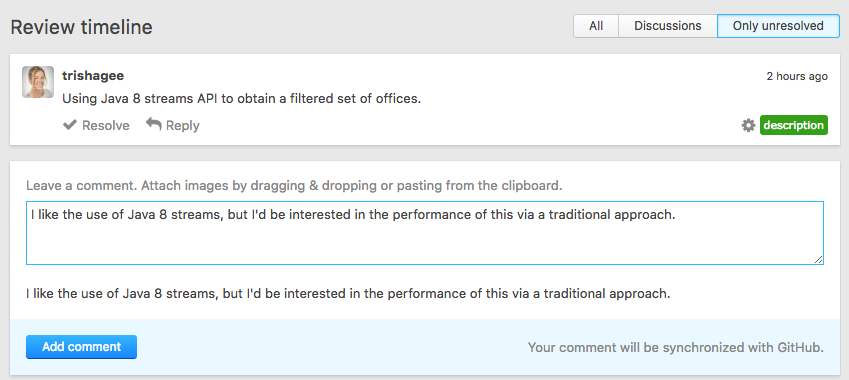

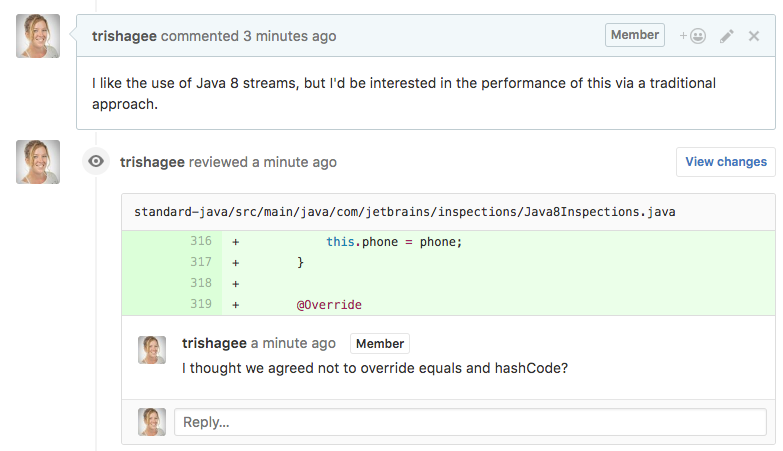

At this point, the project owner reviews the whole thing with one question in mind – is it good enough to merge? Usually there will be some comments, questions or feedback from the reviewer. Like GitHub, Upsource lets you leave these comments either as a review level comment.

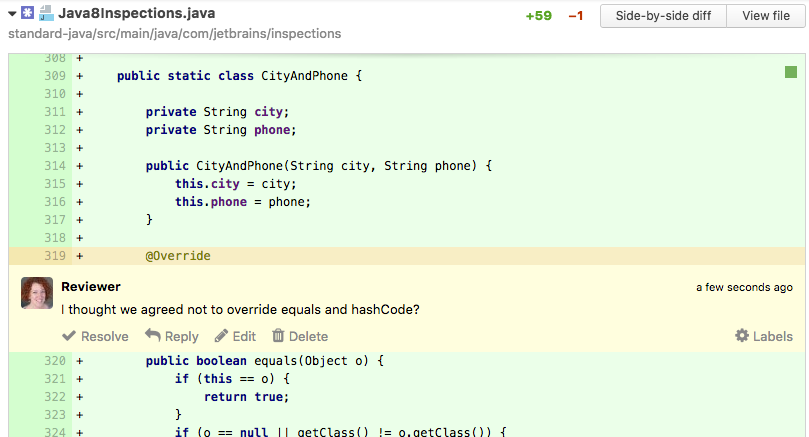

Or at the code level

Comments in Upsource are automatically synched with GitHub and vice versa, so reviewers are free to comment in either tool.

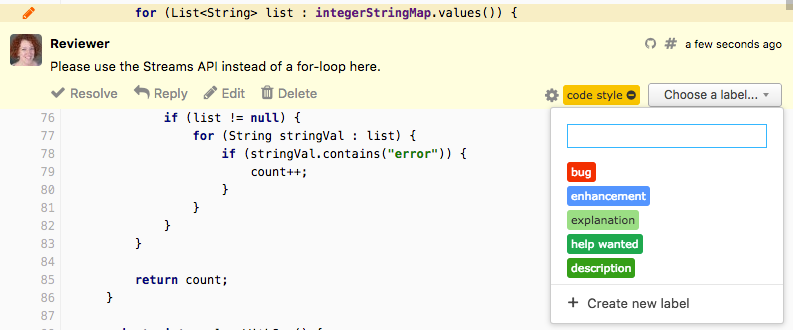

As the code author, it’s my job to look at the comments and either implement suggestions, defend my decisions, or ask questions. In Upsource, comment labels can help clarify whether this is something that really needs to be addressed before the code is merged, or if it’s simply a question to be answered or a comment to note.

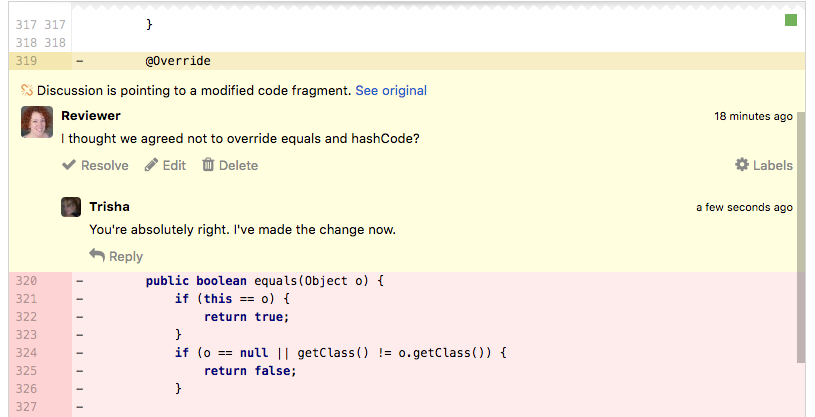

If there are comments that need to be addressed by updating the code, then I will make the changes and then add them to this code review.

It’s possible that we then begin a cycle of suggesting improvements or additions and receiving updated code. In theory, on each iteration there are fewer comments, and fewer/smaller changes that need to be made. Finally, the reviewer should be happy enough with the code to merge it, closing the pull request.

You can even merge from Upsource

Discussion

Because this is a gateway type of process, often the reviewer is more senior, or at least in a position to have final veto over the code. Therefore, during a code review of this type, the author is often defending their design and implementation, and the reviewer is trying to think of reasons why this should not be merged into the main code base.

This can lead to a certain level of antagonism: as the code author, you’ve already invested time writing the code, you’ve thought it through to the best of your ability, and you have a solution that you think works; as a reviewer, it seems that your goal is to think of everything that could be wrong with the code before it is merged in, so you can prevent bad/incorrect/suboptimal code sneaking into your code base.

Many of us have been through these sorts of reviews, and I suspect it’s a reason people react negatively to the idea of code reviews – it feels like a combative experience where no one wins.

This type of review process can work well, however, when the goal of the reviewer is not to prevent bad code from going into the code base, but to add functionality to the project/application, i.e. rewarding reviewers on how quickly they merge in the code. Of course, the danger here is that reviewers will not look at the code properly and simply say “yes”. But given how much can be automated (compilation, tests, inspections, static analysis, performance, security etc), in this kind of review the emphasis could be on making sure the right checks have been automated for this code (e.g. ensuring unit / functional / performance / security tests exist) and ensuring that those checks are testing the right things.

What gateway reviews are really horrible for is checking the design of the code. Really it’s too late at that stage – either the poor author has to throw everything away and start again (is there anything more demoralising as a developer?) or the code needs to be merged in even with its non-standard, non-optimal design. If design and architecture matter to your team and your application, these things need to be discussed before starting the implementation. A gateway code review then simply checks the code follows the ideas discussed, and if it doesn’t, the reviewer assumes the code author had a good reason for this, and perhaps starts a discussion about why the original design expectations didn’t match what was actually implemented.

Let’s distill some of this discussion into the pros and cons of this approach to code reviews.

Advantages

- Someone on the team is ensuring that code that’s merged into the main code base meets the required levels of quality (however that is measured).

- If the process is geared towards accepting, rather than rejecting, code1, these types of reviews can be relatively quick and straightforward.

- If the process is geared towards accepting code, and either expectations around code style/approaches are very clear or a certain amount of inconsistency within the code base can be tolerated, this process can encourage contributions from a wider community of developers (e.g. open source projects on GitHub)

Disadvantages

- The major disadvantage is that the work has already been done. So either the reviewer needs to recognise that the work has been implemented and therefore focus their feedback on only preventing major problems from creeping in, or the code author needs to accept that re-work from a code review could be extensive.

- If the code review is focussed on getting the code absolutely correct2, each iteration of comments/code changes can be fairly long, and there can be quite a lot of these iterations.

- Handing code over to be reviewed blocks progress, so developers following this kind of process often have more than one fix/feature in progress, sometimes several. A lot of work-in-progress and a lot of context switching can be detrimental to a team’s productivity.

- This is not the best way to up-skill developers. Suggestions given once the code is written can be seen as “you did this wrong” instead of “there’s a nice way of doing this thing”, and developers are not as receptive to these suggestions as those received while solution is being created.

Anti-patterns

When gateway code reviews are focussed on getting the code absolutely correct2, these long and plentiful cycles of review/change/re-review/more-changes take longer than the initial code. That makes authors and reviewers dread the death-march of the code review – authors leave it longer before review, meaning much more code goes into a review, and reviewers wait longer before opening and commenting on reviews, both of which lead to even longer reviews. Without clear guidelines on what a reviewer is supposed to be looking for and what is (and is not) a showstopper, even the reviewer can be unable to bring this cycle to a satisfactory end.

To overcome these problems:

- Code reviews should contain a small set of changes that’s easy to review.

- Reviewers should have a clear set of guidelines on what they should be looking for.

- The goal should be to accept the code unless a showstopper is identified.

- Code can be annotated by the author in advance in the code review tool to explain approaches or justify design decisions up front to preempt questions.

Also remember to praise good solutions and nice code, as well as drawing attention to potential problems. This can alleviate the feeling that code reviews are all about criticism.

Suitable for

- Teams with high levels of trust with a shared vision of the code – it’s much easier to accept the code of developers you trust.

- Code bases that don’t need strict control over the design and can tolerate multiple different programming approaches – it’s too late to discuss design or architecture in a gateway code review.

- Teams with alternative channels to discuss design and architecture, e.g. via mail, chat, issue tracker, or even in person, and a process that either prevents implementation before a design is agreed, or actively allows collaboration and feedback during implementation.

- Projects where waste can be tolerated – if it’s OK to throw away contributions. This way an initial “reject” won’t lead to lots of explanations and re-work, but possibly to an alternative contribution from a different developer.

1 Note: a good way to achieve this is to make sure everyone is clear and consistent with what they’re looking for during the review, and what they consider to be a showstopper.

2 For some definition of correct, from the reviewer’s point of view.