TeamCity

Powerful CI/CD for DevOps-centric teams

How Groovy uses TeamCity

This guest post is brought to you by Cédric Champeau, a Senior Software Engineer working on the Groovy language at SpringSource/Pivotal.

NB: starting today Groovy is looking for a new home.

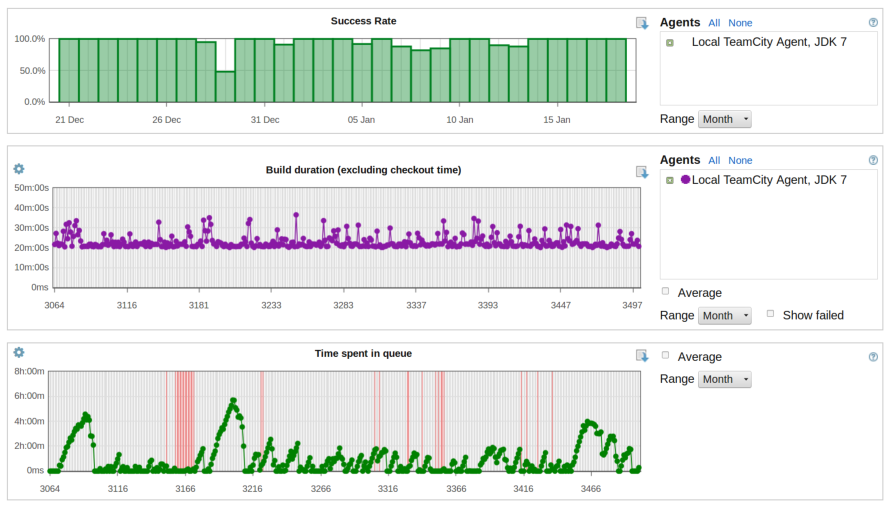

Upgrading the continuous integration chain

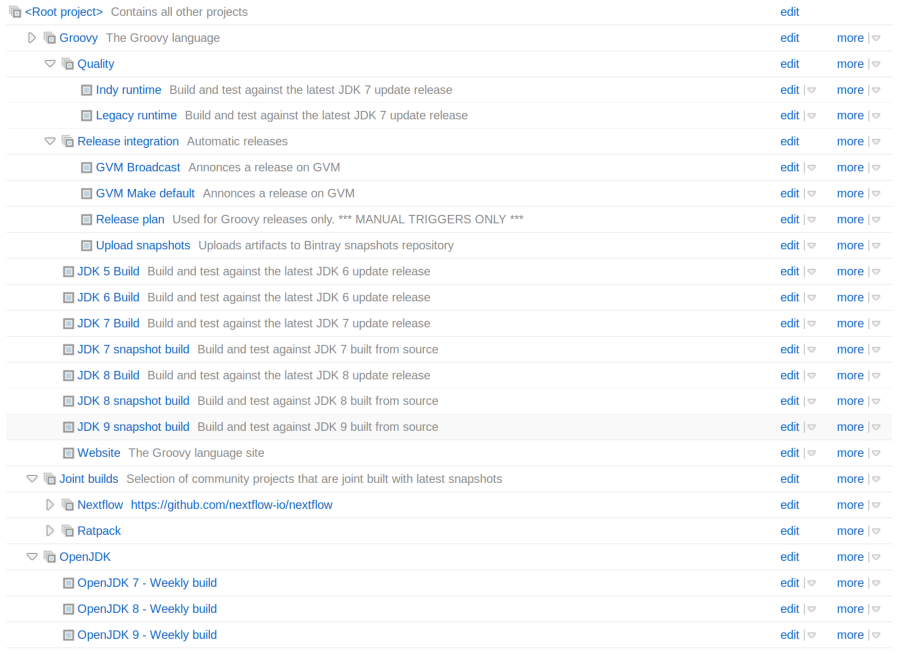

For several months now, the Groovy language has been building a new continuous integration architecture based on TeamCity. We’re running it on a dedicated server sponsored by Jetbrains. One of the key reasons for moving to a dedicated server was the long feedback loop that we had on the Codehaus infrastructure and that classic open-source project CI infrastructures like Travis, based on slow cloud based instances offer: as an example, a minimal build on Travis took as much as 45 minutes. It may sound reasonable for a language like Groovy, but considering that the same build takes around 5 minutes on a recent laptop, there’s something very wrong. And there’s more than a single build to do:

The Groovy project has for example very strict requirements in terms of compatibility with several JDKs. We are testing Groovy against multiple versions of the JDK:

- OpenJDK 5, for any Groovy version before 2.2

- OpenJDK 6, the minimal JDK version for Groovy 2.2+

- OpenJDK 7, with two different runtime versions: legacy and invoke dynamic

- OpenJDK 8, with the same runtime versions as JDK 7

In addition, we test Groovy against early release versions of OpenJDK 7, 8 and even 9! We do that to report bugs to the OpenJDK team before new versions of the JDK go out in the wild. It has become more and more important lately since JDK 7 and the advent of invokedynamic: we have seen many buggy releases of the JDK breaking Groovy, so we really had to find a solution to avoid this as much as possible.

In addition to the combination of JDKs to be tested, Groovy is a widely used language, meaning that we have to support multiple versions. In particular, bugfixes are often backported on multiple branches. This means that we have more than one branch alive. Those days, we maintain Groovy 2.2.x, Groovy 2.3.x, Groovy 2.4.x and 2.5 is coming.

Last but not least, pull requests from the team or the community need to be pre-tested, increasing the combination of builds that we need.

For all those reasons, running TeamCity on a dedicated server looked like the best solution we found. It was also in particular important because TeamCity has the concept of a build agent. Build agents are important because they allow increasing the build capabilities externally. We haven’t done it yet, but one of the key aspects that made us lean towards TeamCity was the ability to build a group of “community driven” agents that would let us test Groovy on a wider variety of environments. In particular, the current builds are all based on a Linux x64 box, but Groovy needs to run on more than that: Windows, Mac OS, … All those environments need to be tested, but are not, because of the lack of build resources for that. This means that in the current architecture, we only rely on some community members who build on Windows or Mac OS to tell us if a build works or not. But we know that with TeamCity, we have a way to improve the situation in the future.

So imagine that each commit on the Groovy project needs to be tested on a combination of JDK, branch, environment, plus pull requests. This requires a lot of work, but TeamCity greatly simplifies this. In particular, the branch combination is reduced to simple configuration : on a build plan for JDK 7 for example, we can choose which branches need to be built. That dramatically reduces the effort needed to have a proper CI toolchain working.

From building to releasing

Another aspect of choosing TeamCity was the ability to simplify the release process. Before the new CI infrastructure was setup, releasing a new Groovy version was a bit complex. It involved building locally, checking the build, creating a tag, pushing the tags on VCS, uploading the distribution through WebDAV, or even the documentation through WebDAV. Last but not least, we also had to take care of synchronizing with Central through the Codehaus repository. Literally, it took hours. Releasing a Groovy version could take as long as a full day.

Since we migrated to TeamCity, we took advantage of using Gradle and Bintray to simplify the process. Using the Artifactory plugin and some configuration, releasing a new version of Groovy is as easy as filling a form in TeamCity.

Everything is built on the CI server, packaged, uploaded to Bintray and synchronized with Central using a single click. Lately we even added support for GVM directly in the release process on TeamCity, meaning that a new Groovy release is automatically promoted on GVM! There is still some manual process involved (for example, the CI server will not decide for itself if a build is considered a major version or not, nor will it automatically update the website to announce a release, or close JIRA versions for us). But what is interesting is that the overall process can be completed in less than an hour, including building, testing, and uploading. It’s a huge win.

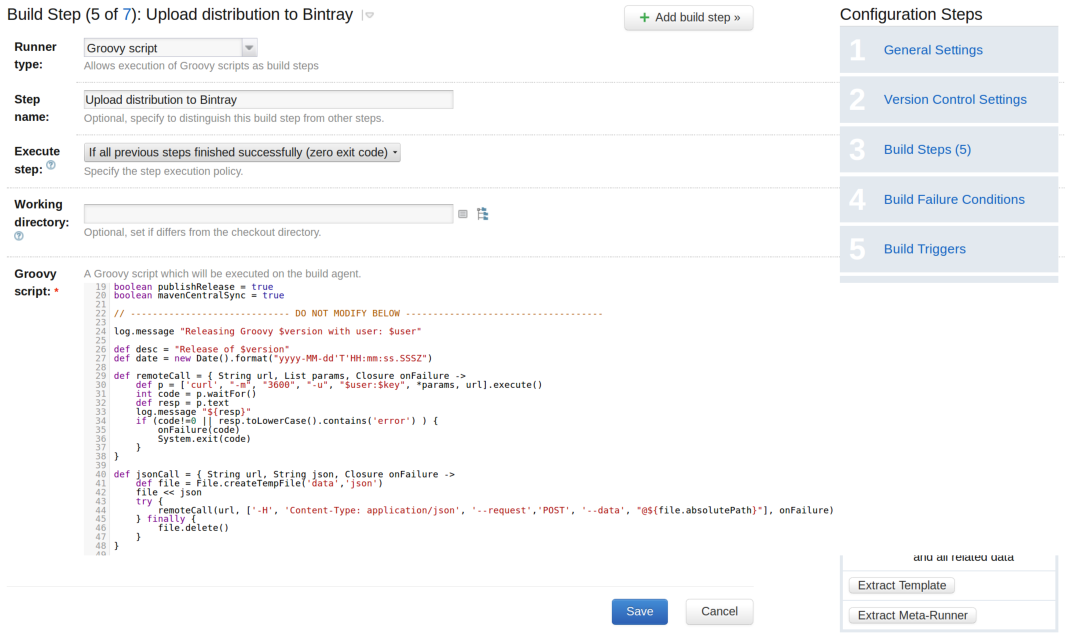

A Groovy plugin for TeamCity

Interestingly, automating the release process soon required capabilities that TeamCity didn’t have out of the box. For example, notifying GVM, cleaning artifacts produced by pull requests, uploading the distribution to Bintray, calling the Artifactory REST API, … All those required scripting capabilities. For that reason, we developped a plugin for TeamCity which allows writing a build step as a Groovy script. The plugin gives access to a lot of information available in the build, like the build number, the branch name, etc… allowing us to trigger specific behavior based on that contextual information. For example, building all those branches on multiple JDKs is very nice, you soon realize that you are filling the disk with artifacts that you don’t want to keep. Unfortunately TeamCity will not let you have custom cleanup rules based on particular variables of a single build configuration. In our case, we wanted to remove the artifacts only for branches built from pull requests, and that is done through a Groovy script used as a build step.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can say that we are very happy with the current status of our continous integration toolchain. We went as far as being able to release directly from the CI server, allowing us to dramatically reduce the errors related to a long, unfriendly human process, as well as dramatically improving our feedback loop (multiple JDKs, pull requests, …).

While the process can certainly be improved, for example by adding support for adding community build agents, doing it with TeamCity was very easy, so we’re very happy that we chose it!

Subscribe to TeamCity Blog updates