.NET Tools

Essential productivity kit for .NET and game developers

Faster Debugging for Massive C++ Projects in Rider

If you work on large Unreal Engine projects in Rider, you’ve likely experienced the dreaded debug-step delay – hit F10 for Step Over, contemplate making coffee, then finally see the next line execute.

These delays occur in LLDB Debugger, the engine behind Rider’s debugging capabilities for C++ and other native languages. After months of focused optimization work, we’ve made significant improvements to our custom version of LLDB on Windows. As a result, Step Over has gotten a major speed boost – up to 50 times faster in certain cases. These improvements will debut in Rider 2025.1 and the EAP builds leading up to it.

In this blog post, we’ll tell you about the game-changing optimizations that got us there.

Creating a benchmarking environment

Our initial challenge was to reproduce the slow stepping behavior users report. Standard Unreal Engine demos weren’t showing the full extent of the problem – the difference between a 10ms and 100ms step isn’t immediately obvious. The real issues emerge in massive projects with gigabytes of debug symbols.

To properly assess the situation and measure our improvements, we generated an extreme test case – a C++ project with a 1 GB binary and 8 GB of debug symbols to amplify the stepping delays our users might encounter.

A look under the hood

To better understand our approach to tackling the performance issues, let’s look at how stepping actually works in Rider.

LLDB Debugger is part of the LLVM-project-compiler infrastructure, designed specifically for C++ and other native languages. As part of the LLVM project, it provides low-level debugging capabilities essential for complex codebases. Rider maintains its own customized version of LLDB to ensure an optimal debugging experience for C++ projects, particularly with Unreal Engine development.

When you press F10, the IDE sends a stepping request to LLDB, which must:

- Find the next stop location (the instruction address).

- Place a software breakpoint there and resume the debugging process.

- After stopping at the instruction address, check if the step is really finished. If not, try again.

- Once the step is finished, restore the call stacks.

- Report to the IDE that the step has finished.

- The IDE requests all call stacks for all threads.

- The IDE requests the visualization of local variables for the current frame from LLDB, which triggers dozens of expression evaluations in LLDB.

This process involves resolving symbols by addresses and names, as well as examining assembly instructions. The larger the debugging program and the more debug symbols it has, the slower these operations become.

Here are some specifics on the optimizations we implemented to address this.

Our optimization strategy

Negative caching

During stepping, LLDB makes numerous requests to debug symbols (PDB), most commonly to use addresses to resolve symbols. For example, when LLDB restores the call stack, it resolves every frame address using debug symbols from the PDB. Very often, the root (the bottom) of the call stack consists of functions like invoke_main(), __scrt_common_main_seh(), __scrt_common_main(), and mainCRTStartup(). These functions are compiled into the user application, but the compiler doesn’t provide debug symbols for them. As a result, LLDB cannot find any debug information for these addresses.

Although LLDB was already caching successful lookups internally, we discovered that it was ignoring failed lookups, which turned out to be surprisingly expensive operations. Our implementation of caching for these failed results gave us an immediate performance boost.

Looking beyond the mutex

Because LLDB is multithreaded, certain operations require mutex locks to ensure thread synchronization. For one, access to debug symbols is mutex-protected, which means we need to be extra cautious with these blocking operations in performance-heavy scenarios. Any slow operation with debug symbols inherently affects the entire stepping process. One such bottleneck turned out to be searching for template function symbols by name.

Why do we need to search for template functions at all? After each step, Rider asks LLDB to show you what’s in each variable in the current frame. To do this, LLDB uses Natvis, which might need dozens of expression evaluations for just one variable. Each evaluation means LLDB has to resolve names in the debug symbols, including trying to match type names against function names.

The core problem lies in how MSVC’s PDB files store template function names. Take test<const char *, int> as an example – LLDB won’t find it because MSVC expects test<char const *,int> (notice how const moved and the spaces disappeared). Previously, Rider’s LLDB would search for test<*> to try to find all possible matches. This is a seemingly simple solution, until you consider how many variations of std::unique_ptr<*> exist in a real project. This wildcard search became painfully slow with thousands of template instantiations.

We solved this by transforming the template name into MSVC’s exact format before searching. While LLDB still adds wildcards, the more specific name pattern dramatically reduces the search scope. This optimization not only significantly reduces template function search times but also fixes incorrect cast expression parsing.

Next line, please!

Rider uses custom scripted thread plans rather than native LLDB stepping, which has Windows-specific issues. But how exactly does stepping work? When you invoke Step Over, you’re telling the debugger to advance to the next line – but finding that “next line” is trickier than it sounds.

The thread plan scans instructions starting from the program counter (RIP in x86_64) until it finds an instruction on a different line or hits a branch instruction (like jmp, call, ret) – even if that branch is on the same line. To actually move to the chosen instruction, LLDB uses software breakpoints, overwriting the target instruction with a breakpoint instruction (int3 in x86_64). After hitting the breakpoint and stopping, LLDB restores the original instruction and checks if this is where we really want to stop.

Here’s where it gets interesting: sometimes that “next line” lands us inside an inlined function. While that’s fine for stepping in, it’s not what we want for stepping over. Previously, when the thread plan detected an inlined function, it had to repeat the whole process – find another instruction, set a breakpoint, and try again. In optimized builds with heavy inlining (very common in STL and Unreal Engine code), this could happen hundreds of times per step! Each round requires at least two memory writes, making it an expensive operation.

Our fix? We now check instructions in advance and simply skip them if they’re in an inlined function.

Is it a call?

Another key optimization focused on how thread plans identify call instructions. While LLDB’s SB API can check if an instruction is a branch, it lacks a direct method to identify calls specifically. This forced thread plans to check instruction mnemonics using the available method, which proved costly – resolving mnemonics requires parsing the complete instruction including operands and comments.

To solve this issue, we added a new method to the SB API that checks for calls by examining the instruction bytecode directly, bypassing the overhead of full instruction parsing.

Measuring the improvements

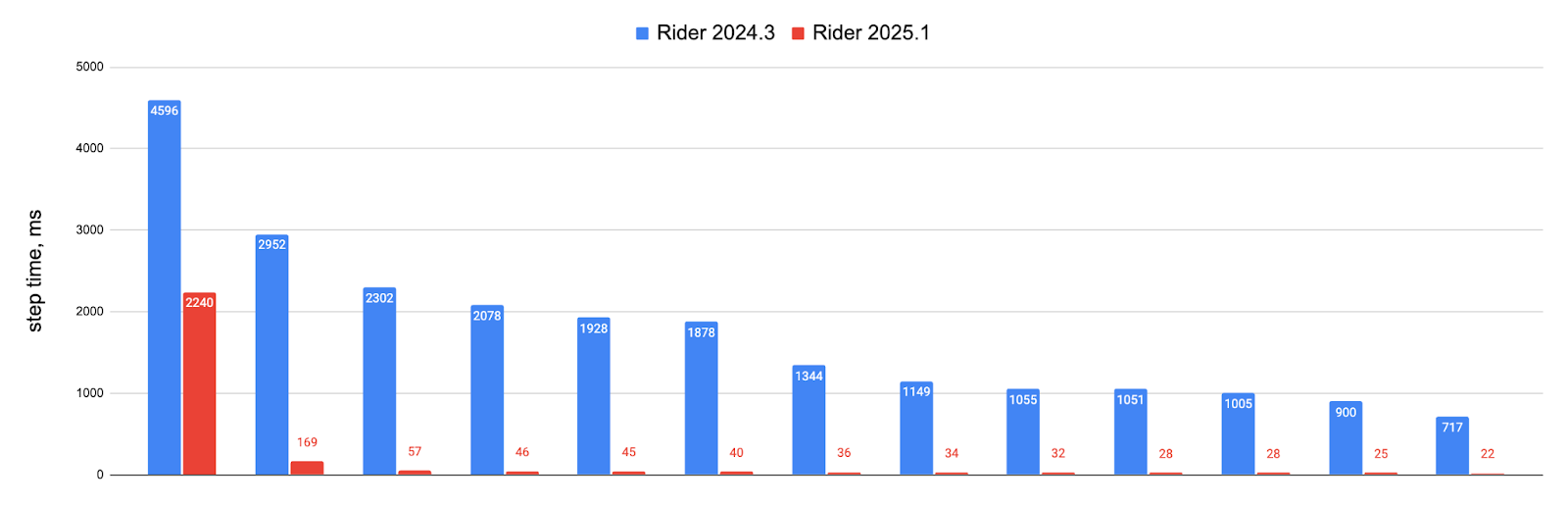

We compared stepping performance between Rider 2024.3 and 2025.1 across several scenarios, measuring the time between sending a stepping request to LLDB and receiving the first frame stack:

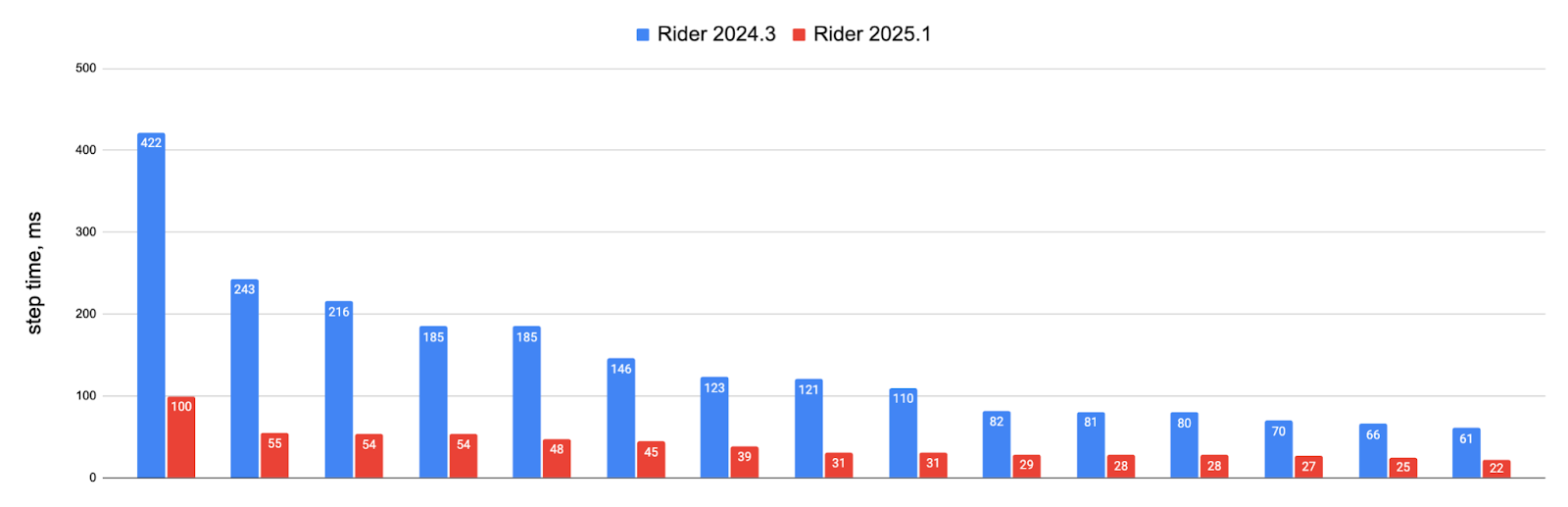

Large C++ project built without optimizations:

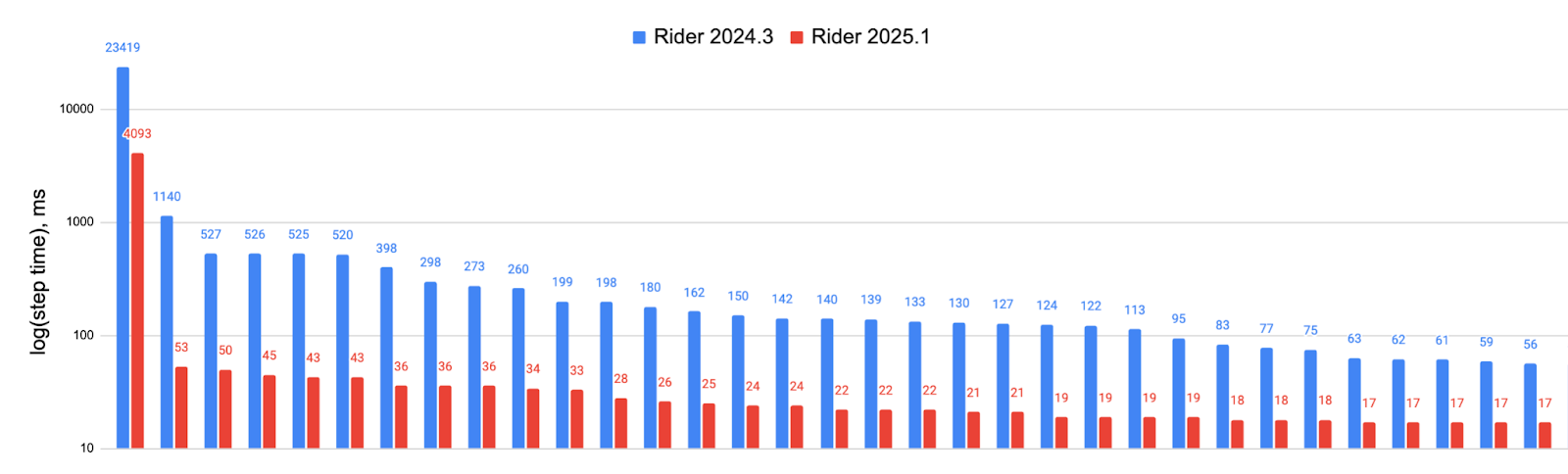

Same project built with optimizations enabled:

Same project build with optimizations, but specific scenarios where stepping operations previously caused 23-second delays:

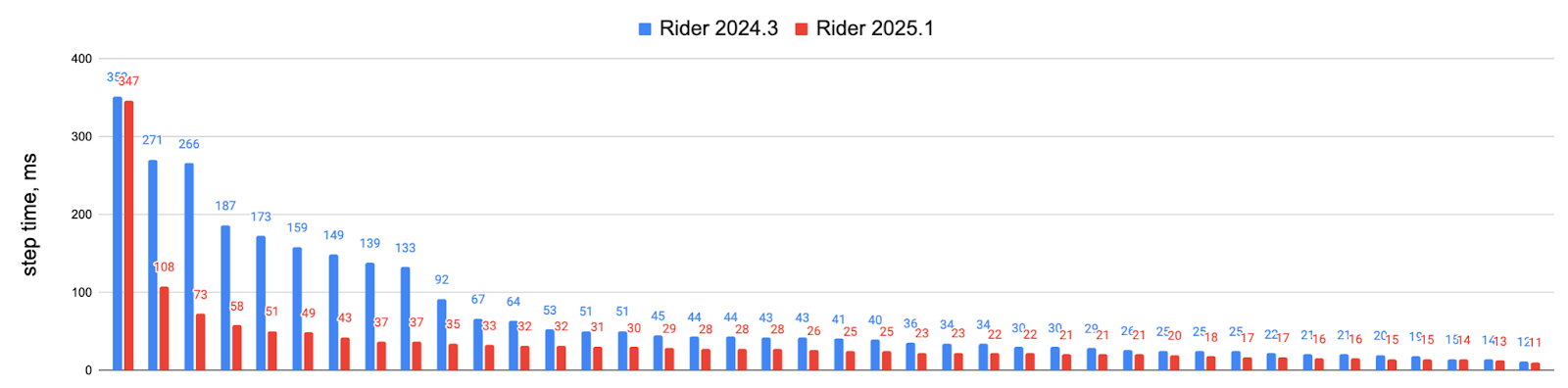

Real-world test using a sample game project built with Unreal Engine (320MB binary, 2.5GB debug symbols):

The improvements deliver up to 50x faster stepping times, with most operations now completing in under 100ms. While these extreme test cases may not reflect every project, developers working with large C++ codebases, particularly Unreal Engine projects, should notice significantly smoother debugging sessions.

We need your help

These debugging improvements will be available in Rider 2025.1, as well as the EAP builds leading up to its release. As we continue to work on the performance of the debugger, we’ll be looking out for edge cases that might need additional optimization. Here’s where your input is invaluable!

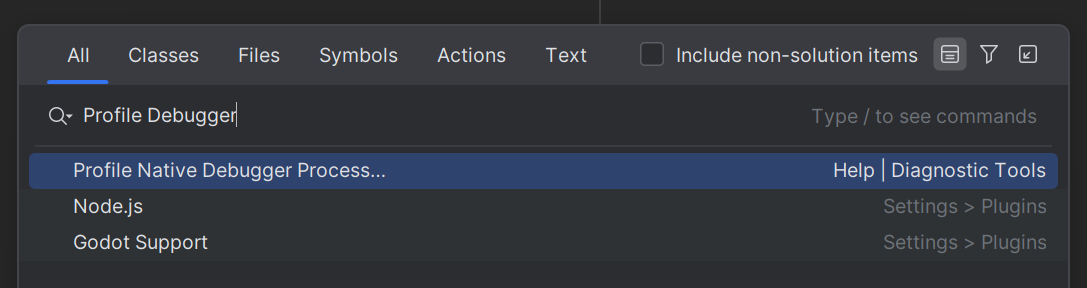

We’ve put together a self-profiler for you to use whenever you’re dealing with slow stepping through C++ code. The Profile Native Debugger Process action can be invoked via Search Everywhere or from the Help menu.

When you trigger this action, the IDE will ask you to grant administrative privileges for profiling. Once you’re done profiling the problematic actions of the debugger, you’ll get a notification with a link to the resulting snapshot. This snapshot can then be shared with us on YouTrack and Zendesk and may be a crucial asset in future investigations. We appreciate your help in perfecting the debugger with us.

Special thanks to:

- Mikhail Zakharov for developing the self-profiler.

- Aleksei Gusarov for thorough code reviews.

Subscribe to a monthly digest curated from the .NET Tools blog: